Nowadays a vampire is usually a Transylvanian in need of an orthodontist. But, as Nick Rennison demonstrates in this entertaining anthology, it was not always so.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula was simply one of a crowd when it was published in 1897. Nor was the novel particularly successful at the time. It was only in the 20th century that Count Dracula became the world’s vampire of choice, and that was due to Hollywood rather than Stoker. Dracula’s contemporary colleagues are ripe, as it were, for exhumation.

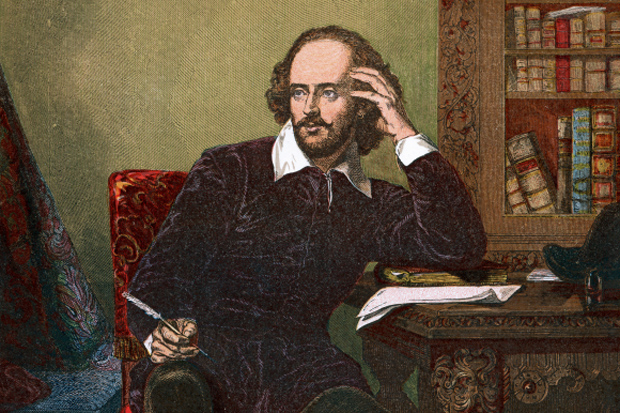

Vampires, particularly in their late Victorian and Edwardian prime, formed a staple of Gothic horror and assumed a variety of guises, some more subtle than others. Their literary ancestry stretched back to 18th-century Germany. Polidori, Byron’s physician, and Sheridan le Fanu were among Stoker’s predecessors.

The 15 short stories collected here provide a formidable gathering of the undead. Some of the authors are familiar: M.R. James leads the pack with ‘Count Magnus’, a textbook example of how to make your readers’ flesh creep as much by what you don’t say as by what you do. E.F. Benson’s ‘The Room in the Tower’ is almost equally good, and a warning to those who have recurring dreams.

Rennison, whose previous books include a companion anthology, The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes, has ferreted out many lesser-known gems. Julian Hawthorne’s ‘Ken’s Mystery’, for example, deals with a young American who rashly falls in love with a young woman in County Cork; even his banjo ends up as an object of horror. Hawthorne, incidentally, was the son of the more famous Nathaniel, and on this showing had inherited a share of his father’s talent.

Another American author, Frank Norris, was a fine novelist in the tradition of Zola. He died young, but not before writing the extraordinary ‘Grettir at Thorhall-stead’, set in medieval Iceland and concerning a very different vampire from the Transylvanian model. The story is written in a strange, high-flown prose that ought to be mildly comical but in fact has a relentless force of its own.

Grub Street was clearly a fertile breeding ground for vampires. Many authors here wrote primarily for money, not art. Some were extraordinarily prolific — the Askews, for instance, a husband-and-wife team, wrote nine novels in 1913 alone. Judging by the quality of their short story, one novel would probably have been too many.

Rennison’s pithy biographical notes are one of the many pleasures of this wide-ranging selection. Augustus Hare’s story is not one of the book’s best, but he deserves inclusion if only for the anecdote quoted here: Somerset Maugham, staying with Hare towards the end of the latter’s life, inquired the reason for some curious omissions in the household’s morning prayers. ‘I’ve crossed out all the passages in glorification of God,’ Hare explained. ‘God is certainly a gentleman, and no gentleman cares to be praised to his face.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £9.49, Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in