Captain Robert Nairac was a Grenadier Guards officer serving in Northern Ireland when on 14 May 1977 he was abducted and murdered by the Provisional IRA. Mystery surrounding the circumstances of his abduction and the fact that his body has never been found have provoked a minor literary industry. This must be the most comprehensive account yet.

Nairac was serving in South Armagh as a liaison officer between the army, the SAS and police Special Branch. He was not a member of the SAS but had vastly more freedom of action than most soldiers, able to travel where and when he chose in civilian clothes with a pistol under his left armpit. On the evening of 14 May he informed a superior officer that he was going to the Three Steps Inn at Dumintree, a well-known Republican haunt where there was live music. There, he seems to have pretended to be a sympathiser from Belfast (he had a good ear for accents and could pass as Irish), even getting on stage and singing Republican songs with the band.

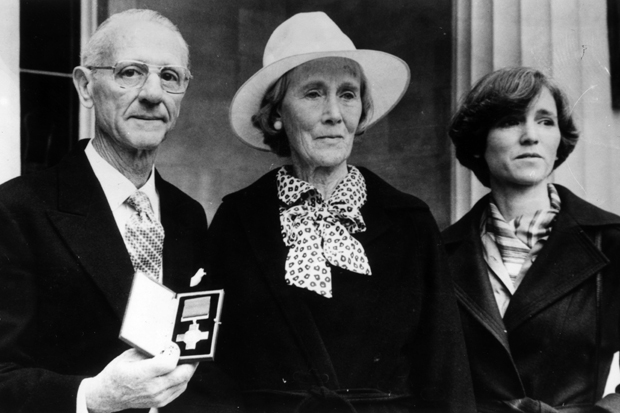

However, he aroused suspicions, at least in part because, despite it being a warm night, he kept his jacket on while everyone else was in shirtsleeves; if he had taken it off he would have exposed his 9mm Browning army issue pistol. He was either followed or lured outside where, during a struggle, his pistol was discovered. He was an Oxford boxing blue and there was a significant fight — teeth, hair and blood were later found — before his abductors got him into a car. He was driven across the border where he was brutally beaten and interrogated. He twice attempted to escape and was eventually shot, without having given away any information. There were rumours that his body may have been fed into a meat-processing plant. He was awarded a posthumous George Cross.

Nairac’s subsequent reputation reflects divisions among those who knew him. All agree that he was courageous, tough, capable, loyal, likeable and a risk-taker, while his army reports suggest a successful career ahead. His detractors, as Kerr calls them, describe him as a loose cannon, unreliable and out of control. He had more than once been fined for missing deadlines, had illegally gone fishing in the Republic, had (unknown to the army) acquired a forged driving licence in another name, had not described in any detail why he was going to the Three Steps, had not requested a back-up (readily available) and had not sent periodic radio signals to indicate that all was well.

His supporters, including Kerr, claim his life was ‘sacrificed to military incompetence and political expediency.’ Hence, presumably, the book’s contentious title. Kerr maintains he was ‘not just’ a liaison officer but that he had an intelligence role, recruiting and running sources. Kerr suspects that he went to the Three Steps to meet a source, that he was ‘there on SAS business’ and that delays in searching for him were attributable to animosity between him and some SAS individuals. Especially blameworthy, in Kerr’s eyes, was the late Clive Fairweather, a headquarters officer with whom Nairac had clashed ‘over what Fairweather perceived as the lack of supervision of Nairac’s activities.’ Fairweather should have reacted more promptly and when he did he ‘went into damage limitation mode. Although Nairac was still alive at this point, rescuing him was not a high priority: Fairweather had his career to salvage.’

These are serious charges, against which Fairweather, who died in 2012, is unable to defend himself. It is true that there was culpable delay in responding to Nairac’s failure to return on time, albeit partly influenced by his history of such failures, and there is no doubt that his superiors should have controlled him more tightly, as Fairweather wanted.

But Kerr’s account, though thoroughly researched, too often merges could-haves into must-haves and might-haves into dids. If Nairac really did run sources and if he really did arrange to meet one in the Three Steps, as Kerr maintains, then he was almost criminally irresponsible. The last place to meet a PIRA source would be in a local bar where people would know him. The last thing Nairac should have done was to draw attention to himself in the way he did. And the first thing he should have done was to ensure back-up in case things went wrong.

Without Robert Nairac we can never know the full story of his brave and brutal end. Chances are, he was freelancing and his courageous enthusiasm, plus a lethal dose of hubris, outweighed his judgment. A sadly unnecessary death.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £13.95 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in