I don’t know if this counts as name-dropping, but I recently interviewed a boyhood friend of Elvis Presley’s in Tupelo, Mississippi. The interview required a bit of patience, because his memories of the young Elvis appeared only intermittently amid a lengthy ramble through more or less anything that crossed his mind. But, as it turned out, it was also good preparation for reading Stop the Clocks.

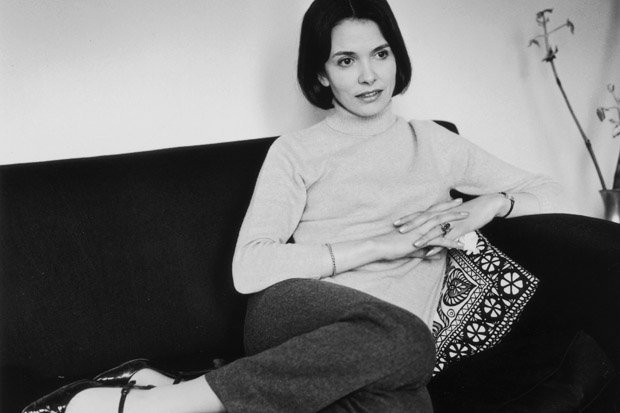

Joan Bakewell published her autobiography in 2003 and this, as the subtitle suggests, is intended to be a far looser set of reflections. Nonetheless, it soon proves so loose as to present a reviewer with the kind of dilemma that could feature in the game Scruples: you’re sent a book by a much-loved national figure, now 82, which, if it were by almost anybody else, you’d be tempted to trash. What do you do now?

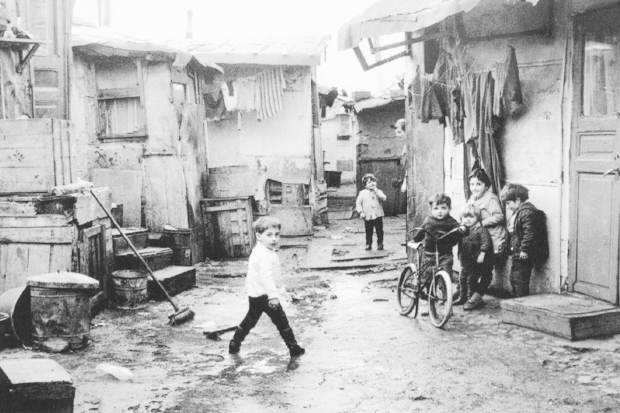

Well, you could start by saying that parts of it work just as the whole thing’s meant to: a neat mix, and occasionally perfect synthesis, of personal experience and social history. In a section on postwar attitudes to sex, for example, Bakewell provides a sharp and heartfelt explanation of why D.H. Lawrence mattered so much to readers of her generation, before regretfully accepting how dated he now feels. And — while it’s not exactly fresh territory — she’s good, too, on the transition from northern lower- middle-class life to Cambridge in the 1950s by way of the grammar school. ‘Remember, girls,’ the headmistress announced when Bakewell got her Cambridge scholarship, ‘however pleased we are for Joan, the true calling of a woman’s life is to be a wife and mother.’

Oddly enough, there are also parts that work just as the whole thing’s not meant to. ‘I don’t want this to be a book about ageing,’ Bakewell writes in the first chapter. Yet, some of its most affecting moments occur when, for instance, she acknowledges ‘an increasing sense of my tribe coming to an end’, or tries to ‘recall what it was like not to be aware of death, how carefree and upbeat that must have been’.

The trouble is that these nuggets do take some digging out from nearly 300 pages of Bakewell telling us whatever pops into her head at any given time: the silly names that celebrities give their children, say, or the approved way of darning socks in the 1940s. (‘A good darn began with the choice of an exactly matched strand of wool or cotton, not only the colour but the ply compatible with that of the sock.’) In fact, virtually all the chapters could be entitled, as one of them is, ‘On Stuff’, with Bakewell proving true to a method that she accurately, if somewhat understatedly, describes as ‘allowing my mind to spool in different directions’. ‘On Stuff’ itself, meanwhile, brings us — among other things — a history of teddy bears, a story she found on the internet about a man in Wales with 4,000 fridge magnets and a reminder of the fuss caused in the 1980s by Kit Williams’s treasure-hunt book Masquerade.

Along the way, Bakewell does sometimes pause to consider the lessons that her long life has taught her — but these rarely tend to the startling. ‘Some things change, and some things stay the same,’ she notes at one point. ‘Some things get better and some get worse,’ she decides at another. Considering the rise of the selfie, she wonders if this is ‘a celebration of our individuality or a desperate bid to be noticed’ — before reaching the conclusion, ‘I don’t know.’

Elsewhere, her conclusions are less coherent. On page 123 she denounces pushy modern parents for pressurising their children to ‘play musical instruments’ and ‘sing in choirs’. On page 125, she laments the clampdown on childhood creativity, with ‘playing music’ and ‘singing in choirs’ both ‘increasingly threatened’. Later, within a single paragraph, she’s both pleased that today’s young people ‘seem comfortable in their own bodies’ and unsurprised by the growth of ‘self-harm, anorexia and depression’.

Almost by the law of averages, even the most rambling sections of Stop the Clocks do contain some incidental pleasures — and I’m not just saying that (I don’t think) because Bakewell is a much-loved national figure of 82. The overall effect, though, is — to reclaim a word from the sort of youth slang that she alternately admires and dislikes — definitely random.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £18.99 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in