When asked the question ‘What is art?’, Andy Warhol gave a characteristically flip answer (‘Isn’t that a guy’s name?’). On another occasion, however, he produced a more thoughtful response: ‘Does it really come out of you or is it a product? It’s complicated.’ Indeed, it’s those complications that make Warhol’s works compelling, as is demonstrated by a new exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

One is that it is hard to tell how much he was really in control. When you look at one of his pictures, are you really looking at the work of his assistants or, indeed, of chance? And the way he forces you to think about that makes you ponder other kinds of art as well. Warhol manages — a characteristic trick — to be simultaneously superficial and profound.

This is not a full retrospective, or even close to one. It all comes from a single private source, the Hall Collection, which means that many celebrated categories of Warhol’s work are omitted entirely. There are no Marilyns, no Elvis Presleys, no electric chairs. But the omission of so much instantly recognisable stuff makes it easier to see what was so original and — in a way — so traditional about what he did.

He shows us the faces of the famous, and that is a reminder of how much art consists of famous faces — kings, saints, gods. Then he repeats them, so you see a whole stack of Chairman Mao, for example, some of which are slightly different from the others. And you respond somehow to those little differences — do they mean anything?

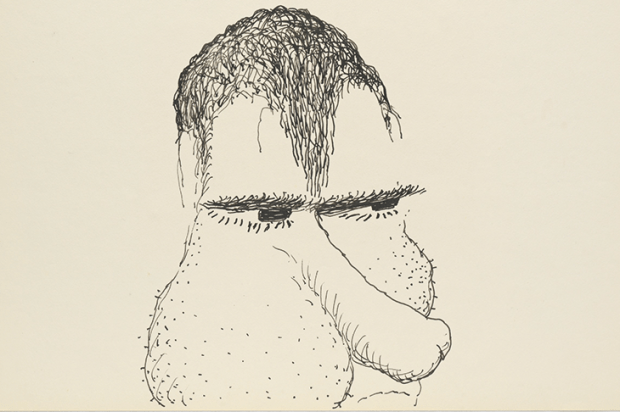

In silk-screening Warhol found a method of making pictures by copying photographs that also generated random variations. One would be lighter, one darker, one smeared, or with the colours out of register. He would produce whole series in this way; the best part of a wall at the Ashmolean, for example, is covered with multiple versions of Joseph Beuys, in alternative colourways. It was the mistakes he liked about the system: he was thrilled because it was ‘so quick and chancy’.

Warhol was obsessed by movie stars and celebrities, but he was also fascinated by randomness. There are works on show in Oxford that represent shadows, a Rorschach inkblot and cloudy stains caused by urinating on specially prepared paint (Warhol claimed not to have the heart to explain this technique to some old ladies at an exhibition, ‘especially as their noses were right up against them’).

Matisse famously advised those who wanted to take up art first to cut out their tongues. Warhol didn’t do that, but nor did he give much away about the meanings of his works. He preferred wit and gossip. Over dinner, David Bowie once told me about his first meeting with the artist, who was then considerably more famous than he was — this was in 1971. Bowie began by telling Warhol how much he admired his work. There followed an awkward silence, until eventually Warhol lent across and confided, ‘I really like your shoes!’ After that, according to Bowie, conversation flowed more freely.

It is no accident that one of Warhol’s final projects was a series of variations on Leonardo’s ‘Last Supper’ (nor that, despite the ironies and outrages, Warhol was a devout, mass-attending Catholic). Like many iconoclasts and revolutionaries he turns out, on closer examination, to have been a closet traditionalist.

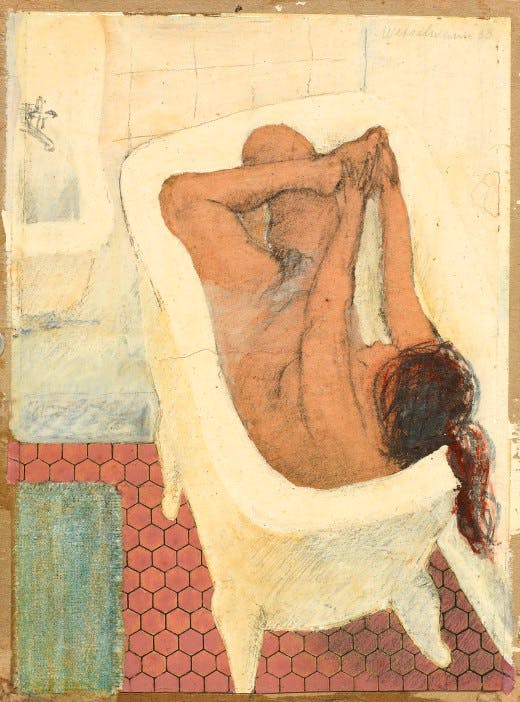

‘Little Bathtub Collage #2’, 1960, Tom Wesselmann

The same could be said of the other major American pop artists. A photograph in the Oxford catalogue shows them all lined up in 1964: Warhol, James Rosenquist, Claes Oldenburg and Tom Wesselmann. Of those Wesselmann (1931–2004) is perhaps the least familiar in this country, but an exhibition of his early work at the David Zwirner gallery suggests he is an artist more subtle and complex than first appears. He tends to be known, if at all, for a series, collectively entitled ‘The Great American Nude’, which might be described as modernism meets Playboy.

This delightful show catches Wesselmann in the late Fifties and early Sixties, just at the point of emerging into maturity. The little collages displayed in the downstairs gallery are engaging interiors plus a still life or two in which the intimacy of a Vuillard or Bonnard is spliced with a bit of American directness (and occasionally what look like bits of the Stars and Stripes). The results are sophisticated but with folksy touches. As you look, you understand how Wesselmann’s nudes, apparently so brash, are descended from those of Matisse.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in