Everyone, we hear these days, must learn to code. Being able to program computers is the only way to be sure a computer can’t steal your job. So doctors, dancers, drivers and dieticians must all acquire programming skills, and coding needs to be at the centre of modern secondary education. Well, evidently it is in the interests of giant technology corporations to have future generations of employees educated to their precise specifications at the public expense. The message is amplified by journalists anxiously extrapolating from their own predicament. (Generating ‘content’ is an increasingly unrewarded dead end; the cool things are data and ‘sharing’.) But the all-must-become-programmers idea does imply a rather weird future culture. If everyone spends all their time programming computers, who will till the fields? Who is going to produce literature?

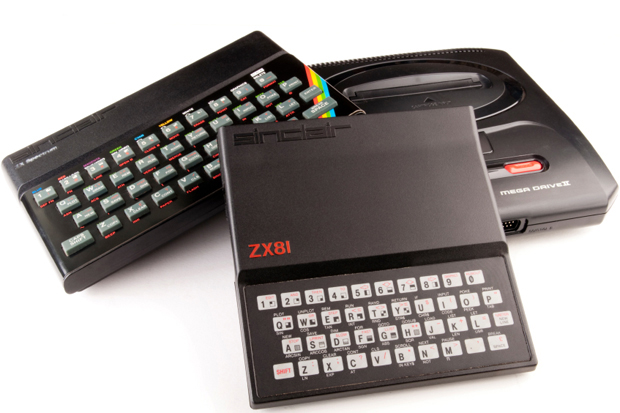

If you can’t code, saying such things risks a charge of Luddism. Luckily, I can after a fashion, having learned on a small black plastic box with blocky monochrome graphics and a laughable 1K of memory: the ZX81, launched in 1981 by Clive Sinclair. The next winter, in a kind of Banksy-style art raid, I snuck into a local department store after school and programmed its colour successor to draw a Christmas tree. That was the ZX Spectrum, which made home computing accessible and unthreatening to millions of Britons for the first time.

Tom Lean’s detailed history of this 1980s revolution will be a joy to anyone who also grew up in the period, but what he also shows very adeptly is just to what extent history is currently repeating itself. All the digital ideology of today, right down to the insistence that teaching everyone how to program computers is an urgent necessity, was in full bloom 30 years ago. The Thatcher government launched a visionary computer-literacy initiative, and the ‘BBC Micro’ became the de facto educational computer in schools all over the country.

But then something unexpected happened. Most new computer owners did not in fact learn to code: they ended up relying on software other people had written, which they loaded in from cassette tapes. And most of that software was not educational or businesslike. The lasting revolution that these machines started was the revolution in video games. There is a direct line from 3D Monster Maze — a black-and-white ZX81 game featuring a terrifying Tyrannosaurus Rex – to Tomb Raider and beyond. A key cohort of early Spectrum or Commodore 64 owners later found themselves the directors of enormously successful video games businesses. (Others ended up writing book reviews for The Spectator.)

Electronic Dreams is full of revealing interviews with the basement electronics-tinkerers who invented whole new computers in a week, as well as hints at alternative paths that history might have taken. (There were several proto-internets, such as the Post Office’s networked computer system, Prestel; and Sinclair’s doomed QL was in some ways more revolutionary than the Apple Mac.) But Lean does not point out another major legacy of this era: its huge impact on the subsequent evolution of electronic music, thanks to the Commodore 64’s legendary SID audio chip and the Atari ST’s built-in Midi ports for connecting keyboards and synthesizers. Overall, he seems faintly to regret the way the home computer became just a ‘software player’ rather than a tool for programming. But there are plenty of ways to be creative with computers that are just ‘software players’, if the software in question is designed for musical composition — or even for word processing.

Today we carry around pocket-sized computers that are vastly more powerful than a ZX Spectrum, but we treat them essentially as collections of apps. And yet it’s easier than ever before to learn programming, if one wants to. (The internet is good at many things, but the thing it’s absolutely best at is being a giant interactive encyclopedia for teaching people how to build the internet.) The truth is that not everyone needs to learn how to drive trains or make wine for us all to enjoy being able to travel and drink. In the same way, we don’t all need to learn to code, and we never did.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16.99 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in