On 7 February 1506, Albrecht Dürer wrote home to his good friend Willibald Pirckheimer in Nuremberg. The great artist was having a mixed time in Venice: on the one hand, as Dürer explained, he was making lots of delightful new acquaintances, among them ‘good lute-players’ and also ‘connoisseurs in painting, men of much noble sentiment and honest virtue’. However, there was also a very different type lurking in the early 16th-century Serenissima: ‘the most faithless, lying, thievish rascals such as I scarcely believed could exist on earth’.

Dürer hints that among these latter were painters, perhaps including some whose works will be seen in a forthcoming exhibition at the Royal Academy, In the Age of Giorgione. Conceivably one who got on the wrong side of Dürer was the shadowy genius himself, Giorgione of Castelfranco.

Of the great masters of the early 16th century, Giorgione (c.1477/8–1510) is by some way the most elusive. Unfortunately, he did not write home to Castelfranco — a fine fortified town in the Veneto — or if he did no correspondence exists. Indeed, not much survives at all, either in the way of evidence or of art. He died young, probably in his early thirties and of the plague. Giorgio Vasari, author of the great Lives of the Artists, tells us that he ‘took unceasing delight in the joys of love’, which is plausible enough given the amorously poetic mood of some pictures by — or attributed to — him, and his development of a new sort of nude.

Apparently, it was Giorgione, whose name just means ‘big George’, who first combined the anatomy of a classical marble Venus with the delicately fleshly sensuality made possible by the oil medium (especially practised in the softer-focused fashion he may also have pioneered). Vasari also relates that the ‘sound of the lute gave him marvellous pleasure’, and Giorgione himself sang and played so well that he spent a lot of time performing — which may help to explain why there are so few of his paintings now.

However, Vasari was writing decades after Giorgione’s death and, as a patriotic Tuscan, he was distinctly hazy about Venetian art in general and Giorgione in particular. Though he did not mention Giorgione, Dürer was on the spot at the time. And his complaint about the younger painters of Venice was that they stole his ideas (he may, as we shall see, have had a point). Dürer specifically excluded the venerable Giovanni Bellini, then aged around 76, from his vilification. Bellini, he wrote, though old, ‘is the best painter of all’.

In making that last judgment, however, Dürer may not have been completely up to speed. In 1506, the elderly Bellini was being challenged by Giorgione, so much so that the wily old fellow eventually incorporated some aspects of the younger man’s style into his own. Indeed, around the time Dürer wrote his letter, Giorgione was influencing so many other artists that it is now very hard to say which are by whom. As Per Rumberg, the curator of the RA exhibition, ruefully explains, ‘Usually the disagreement between scholars about attributions is around the fringes; with Giorgione it’s at the core.’

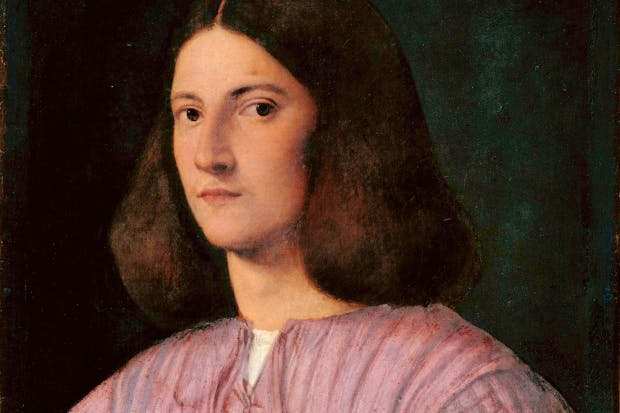

Wisely, therefore, the exhibition is not simply devoted to Giorgione himself but to his era, in which a new kind of painting emerged in Venice — which, for want of a better word, is dubbed ‘Giorgionesque’. It will contain some pictures that most agree are by Giorgione, others that might possibly be by him, still more that are fairly definitely the work of other artists such as the young Titian and Bellini. One, a portrait of an unknown man from Berlin in a smart violet doublet, is widely believed to be a Giorgione (but, as it happens, Per Rumberg himself believes it is by Titian).

There are a few solid clues, however, to the truth about Giorgione. At the start of the Royal Academy exhibition will be a tiny image of an anonymous man, often dubbed the Terris Portrait, from the name of a previous owner, a Scottish coal merchant. This is close in Giorgione terms to a Rosetta Stone, albeit an ambiguous one. On the back, early in the 16th century, someone wrote the words ‘by the hand of Zorzi da chastel fr[anco]’, ‘Zorzi’ being a Venetian version of Giorgione. There follows a date, which starts ‘15’, but then gets much less legible.

This is a typical Giorgione conundrum. The Terris Portrait is among the most certain among that tiny group of paintings almost everyone agrees on — because of those words on the back. There are no signed Giorgiones, and only one other with a similar contemporary inscription naming him as the artist and giving a date. The snag is in the smudging of the last two digits: some connoisseurs have confidently read it as ‘1510’, others as ‘1508’. Per Rumberg laments, ‘So here we have a date but we can’t read it!’

The consensus at the moment, however, is that the date is ‘1506’, so just about the time Dürer was writing home to Nuremberg. His Italian friends, Dürer confided, advised him not to eat and drink with the Venetian painters (the patriarchal Bellini apart), perhaps in case they took the opportunity to poison him. Their behaviour, in Dürer’s view, was low. ‘Many of them are my enemies and copy my work in the churches and wherever they can find it; afterwards they criticize it and claim that it is not done in the antique style and say it is no good.’

The Terris Portrait supports this charge, but only up to a point. It was painted by someone who had learned the lessons of northern masters such as Dürer, for example in the wonderfully delicate softness of the sitter’s hair in which it seems to be possible to count each strand. Giorgione probably did have a good look at any paintings he could find by Dürer (and might well have disapproved of their lack of classical style).

Giorgione must also have experienced the work of Leonardo da Vinci, who had passed through Venice in 1500. Per Rumberg explains, ‘We are not sure if they met, but the Terris Portrait suggests they did, and that Giorgione learned his lesson.’ The smoky, blurry shadows of the man in the Terris Portrait do indeed make him look a little like a male Mona Lisa.

So Giorgione made his new art out of high-quality ingredients — a touch of Dürer, a soupçon of Leonardo, a solid foundation of Bellini and Roman antiquity. But there is something else you feel in a painting such as the National Gallery’s ‘Il Tramonto (The Sunset)’. In the landscape behind some enigmatic figures, a single sapling is silhouetted against the rosy glow in the sky. The story the picture once told has been lost (and further confused by a 20th-century restorer who added a St George and dragon). But the elegiac mood lingers in your mind. ‘Giorgione was a very quiet artist and very emotional,’ Per Rumberg concludes, ‘interested in very personal encounters.’ That’s perhaps about as close as you can get to defining the Giorgionesque effect.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in