Listen

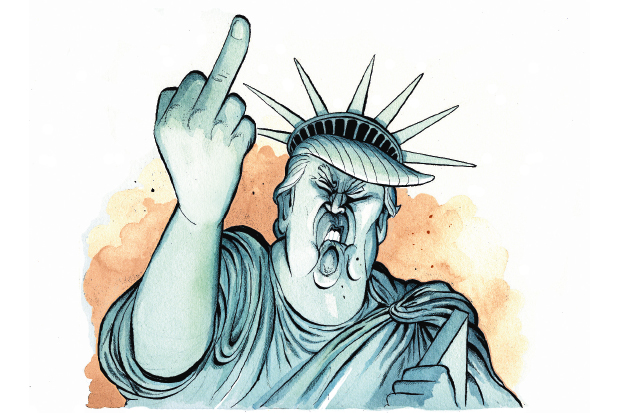

Is Boris Johnson turning into the thinking man’s Donald Trump? Just like the Donald, he’s got funny hair, charisma, and an appetite for women. He may not be as rich as Trump — although we were all impressed by his latest contribution to the Exchequer — but he makes up for that by having a much bigger vocabulary. He’s also able to get away with saying outrageous things because people think he’s entertaining. And in his efforts to persuade Britain to leave the European Union, Boris seems to be appealing to the same anti-politics mood that Trump is exploiting across the pond.

No, I’m not talking about that ‘part–Kenyan’ remark about Barack Obama, which has been taken out of context. I mean his dredging up of that faux outrage which was Obama’s decision to remove a bust of Winston Churchill from the Oval Office, and his conspiratorial mutterings about the CIA’s involvement in the formation of the European Union. Michael Gove, the other Tory big beast in the Vote Leave campaign, hardly struck a blow for sanity when he said a vote to remain in the EU would leave the British looking like ‘hostages locked in the back of a car’.

Vote Leave has been eager to distance itself from the fruitier elements of Ukip and the Tory right. God forbid anybody calls them swivel-eyed. But in politics today, crazy is all the rage. No matter how much the ‘out’ campaigners may want to sound normal and positive, they know that to win they must tap into the same forces which are pushing Trump towards the Republican nomination — a distrust of the political elite and a fury at the lack of democratic accountability in this bewildering age of globalisation.

That’s where the political energy is on the right. Everywhere you look, in country after country, batty nationalists are winning and conservative pragmatists are running scared. The victory on Sunday of Austria’s Freedom party candidate, Norbert Hofer, who likes to carry a gun, is just the latest in a series of gains for this new right-wing populism. We see it happening across Europe — in Germany, France, Denmark, Sweden, Holland, Finland, Greece, Italy, Poland, Hungary, not to mention Switzerland.

The extent to which these movements can be described as ‘fascist’ or even ‘far-right’ varies in each case, as does the credibility of their threat to the status quo, but what unites them is an unconservative rage against the ‘system’, and a desire to punish established right-of-centre parties for having betrayed their people. The paranoid style in American politics, first identified by the historian Richard Hofstadter in the Republican party as long ago as 1964, has gone global. What Hofstadter called ‘heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy’ pretty much defines conservatism everywhere.

As Kurt Cobain put it (quoting Joseph Heller), ‘Just because you’re paranoid don’t mean they’re not after you.’ And just because people are angry doesn’t mean they’ve gone round the twist. If you are a German whose country has just accepted 1.5 million immigrants in one year because Angela Merkel wanted to show the world (or Facebook) how kind she was, you might understandably feel disenfranchised, and want to support the radical Alternative für Deutschland, or attend one of those anti-Islam Pegida rallies. If you are a Frenchman living under President François Hollande’s seemingly permanent ‘état d’urgence’ after several appalling terrorist attacks in Paris, you might begin to understand the appeal of Marine Le Pen. And if you are an unemployed Italian, whose country has had three successive unelected prime ministers, you might have good reason to think that democracy is a sham. It’s a logical response to an illogical world.

The right has lots to be angry about. The trouble is that conservatives are not just mad in the American sense, meaning cross; they are mad in the English sense, meaning insane. As Charles Moore put it in The Spectator a few weeks ago, what we see in the rise of Donald Trump is political incorrectness gone mad. People are so fed up of being told not just what they can or can’t say but how they should think that they are lashing out in all sorts of weird directions.

Trump’s popularity is pushed online by an increasingly bizarre movement known as the ‘alt-right’. This is a ragtag army of professional trolls on Twitter, libertarian bloggers, and hard-right activists, bound by nothing other than a shared love of offending politically correct sensibilities. The alt-right is not purely in it for the LOLs, however. Its followers also flirt with misogyny and white supremacy, then plead irony when they are called out as sexist or racist. In Trump, a.k.a. ‘Daddy’, they have an ideal candidate. It’s all very hilarious. It’s also deranged.

The left has gone bananas, too, of course. Jeremy Corbyn is leader of the Labour party, remember. That leather-clad cypher Yanis Varoufakis is considered a major public intellectual. But centre-left parties can still deploy a unifying vocabulary of -economic justice and human rights that speaks to issues of inequality across borders. The right, on the other hand, is torn between its enthusiasm for international capitalism and its love of country and tradition.

In recent years, the British Conservative party appeared to have solved the conundrum — to outside observers, at least. David Cameron just about won an election in 2010, then triumphed last year. Jealous American moderates looked to Cameron’s example as a model for how, post-crash, a right-of–centre party could seize and hold power. Cameron, they said, had successfully modernised the Tories. He’d embraced socialised healthcare, gay marriage and environmentalism, which made him acceptable to the mainstream, while being tough (or tougher) on immigration and government overspending, which kept the right happy. He’d compromised his way to victory, as great Conservatives do.

How silly that argument looks now. As every Tory knows, there is no Cameron-ism. The Big Society agenda — the Burkean waffle about little platoons — was a philosophical fig leaf for a party that was making up its beliefs as it went along. David Cameron has never come close to building any grand coalition; he has been lucky. He won last year’s general election because the opposition was led by Ed Miliband; because Scottish voters dramatically deserted Labour for the SNP; and because Conservative voters believed that his bold reforming agenda had been checked by the Liberal Democrats.

In Britain, the right-wing insurgency represented by Ukip would already be a major parliamentary force were it not for the first-past-the-post system (peace be upon it). If the House of Commons were chosen according to a proportional system, Ukip, having won almost 4 million votes in May, would hold around 80 seats. And Nigel Farage’s barmy army might well have made even greater strides had it not been for the fact that Cameron had offered a huge pre–election sop to the right by promising a referendum over Britain’s EU membership.

Now the referendum has come back to bite Cameron, and his luck is running out. The Brexit debate is having a similar effect on the Tories as Trump’s candidacy has had on the Republicans, forcing the party to confront the very real possibility of its imminent demise. Whether or not Trump becomes the party’s nominee for the presidential election in November, the Republicans now look sunk. The same applies to the Conservatives and the referendum. If the country votes to remain, David Cameron will have alienated a majority of his party’s support, possibly forever. If the country votes to leave, David Cameron, the first successful Tory leader in a generation, will have to resign.

The Brexit issue has forced Cameron’s party to ask itself questions that centre-right parties everywhere would really rather avoid. Is economic growth more important than national sovereignty? And is our country really that great? For decades, Conservatives have muddled on by insisting that, while Britain may be going to dogs, it’s the fault of the nanny state or the EU. But the possibility of leaving the European Union has exposed the doublethink at the heart of modern conservatism, which is that it wants to be at once patriotic and self-loathing.

And if you want to see where patriotic self-loathing gets you, look at Donald Trump. His campaign to Make America Great Again sounds upbeat, but the message is fundamentally negative. Trump says that the greatest country in the world has been wrecked. He tells Republican voters that the American Dream is dead and that Washington and their party have sold them out — and they love him for it.

Maybe the wonks in Washington who wanted the Republican party to imitate Cameron had things the wrong way round. After all, Cameron’s ‘compassionate conservatism’ was initially borrowed from George W. Bush. Like the Cameroons, the Bushies tried to ‘achieve progressive ends by conservative means’, whatever that meant. But the Republicans are now learning that, to survive, a party must demonstrate compassion to the people who actually vote for them, not just the people who might. The Conservatives may soon be taught the same lesson.

For decades, the Republicans pretended to hear the concerns of their lower-class voters about issues such as immigration, only to ignore them when it came to enacting policy. You can only do this so many times before voters find a way to punish you at the ballot. In 2016, the Republican electorate have rejected all the establishment’s preferred choices. Their second choice is Ted Cruz, a hard-right conservative and fervent evangelical, who is unacceptable to the more moderate party elite. But their first choice is a mad postmodern joke: a billionaire who doesn’t seem to stand for anything beyond offending people, and who is so used to being a TV star that he cannot distinguish between his ‘polls’ and ‘ratings’. Perhaps we are seeing the future of right-wing politics, and it’s Donald Trump.

The British pride themselves on not giving in to extremism. We never embraced communism or fascism because we are inherently conservative. But all over the world, conservatism is having a nervous breakdown. The right is tearing itself apart. And the EU referendum is proving that British Conservatives can be as barmy as everyone else.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in