Disguises and mistaken identities are a staple of opera, but usually as part of the onstage, not the offstage, action. So what are we to make this week of a Handel opera that isn’t by Handel at all, and a Mozart opera that was largely composed in 1990? As usual in the opera house, there are good — if complicated — explanations.

Every year the London Handel Festival tests the theory that forgotten operas are forgotten for a reason, rooting around the darkest corners of the composer’s output to find some abstruse treasures for their audience. This year they’ve outdone themselves, with a performance by Opera Settecento of Elpidia — an opera not heard since its initial run in 1725. The reason? Elpidia is a pasticcio, a collection of arias mostly by Vinci (with a few also from Capelli, Lotti and Orlandini) strung together with original recitatives by Handel.

Such a cut-and-paste approach might not suit our purist, contemporary idea of artistic creation, but the result is superb. Not bravura, coloratura superb, but psychologically sensitive, with melodies designed to emote rather than impress. This is music that transcends (even if it can’t quite transform) a frankly weak plot involving Romans, Goths and a rather half-hearted love triangle. The only problem is that it’s a score that sends you home dying to hear Vinci’s Rosmira and Ifigenia — sources for the greater portion of the arias — rather than revisit Handel’s own operatic collage.

The Handel Festival’s stubborn refusal to offer surtitles meant that it was all but impossible to follow the plot, forcing conductor Leo Duarte and his cast (hidden behind both the orchestra and a wall of music stands) to sustain the drama on a purely musical level. Countertenors Rupert Enticknap (Olindus) and Joe Bolger (Ormonte) made a feisty pair of lovers, their rivalry heightened by strikingly different vocal personalities. Muscular, agile and strongly projected, Enticknap is one of the most exciting young countertenors around, overpowering the lyrical, softer-grained Bolger on this occasion, whose role seemed to sit a little on the low side. Rupert Charlesworth impressed as charismatic baddie Vitiges, and an underused Chris Jacklin made the most of his brief appearances as Belisario. With such a strong vocal showing it’s just a shame that the orchestral strings, strongly led by Bojan Cicic, seemed unable to agree on tuning.

But for all Epidia’s unexpected strengths, the stand-out of this year’s festival was easily Alexander Balus. Handel’s oratorio gets bad press from scholars. Winton Dean memorably dismissed Act I as ‘the dullest single act in any of the oratorios’, but it all rather depends what you look for in the genre. If it’s pacy, action-driven drama, then yes, you’d be better off elsewhere, but if it’s colourful scoring and some exceptionally lovely arias then you’d struggle to do better.

Cleopatra’s ‘Convey me to some peaceful shore’ (sung exquisitely here by Katherine Watson) is a Shakespeare monologue in music — all rueful loss and dignity — and the carefully coloured orchestral writing offers narration clearer than any libretto, especially when conducted with as much energy and love as Laurence Cummings has to offer. Add a heavyweight, international cast including the vivacious Sophie Junker and mezzo Renata Pokupic, and you have a Handelian winner.

It’s quite a week when an all-but-unknown Handel pasticcio isn’t the most obscure opera on offer. Step forward Mozart’s unfinished The Goose of Cairo. While Mozart dominated the London Mozart Players’ publicity, top billing should really have gone to Stephen Oliver, the contemporary composer whose music makes up more than half of this particular completion. Faced with unperformable fragments of music, Oliver eschews pastiche in favour of an altogether more bracing solution: juxtaposing music in his own vernacular style with Mozart’s surviving arias.

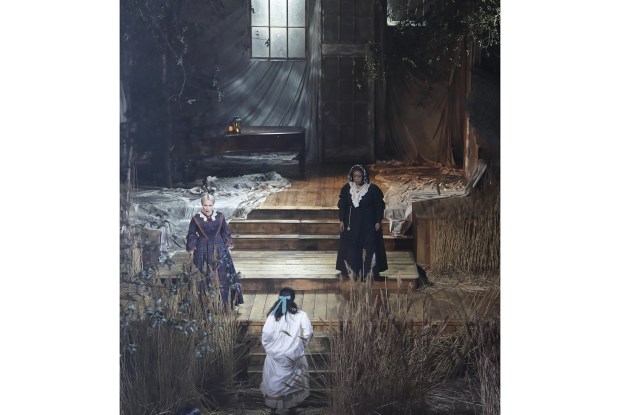

It’s all frightfully postmodern — a metatextual opera (and who doesn’t enjoy one of those on a Friday night?) that rubs 18th-century idiocy up against 21st-century irony. The result is so frustratingly, so nearly brilliant that it hurts to admit that it doesn’t quite work. That may have been down to a performance blighted by environmental issues. The lack of synopsis, surtitles or libretto set the audience on the back foot from the start, leaving us groping around in the booming acoustic of St John’s Smith Square for any verbal clues as to what was going on. And then there were the balance issues caused by the awkward, parallel placement of orchestra and singers.

But none of this could damp the verve of a cast who gamely switched between comedy and contemplative nihilism, between Oliver’s angular idiom and the generous lyricism of mature Mozart (Goose was written concurrently with Entführung). From Elli Laugharne’s tireless Auretta to Fflur Wyn’s passionate Celidora and the comedy double-act of Robert Murray’s Biondello and Christopher Diffey’s Calandrino, all were excellent — characters in search of a composer, but finding themselves sent instead on a musical wild goose chase.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in