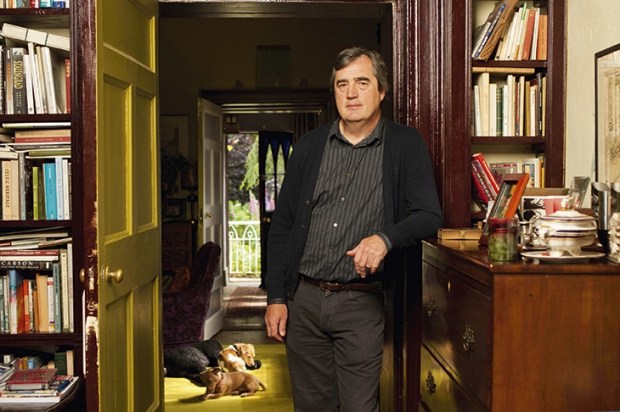

‘In many ways,’ Georg Baselitz muses, ‘I behaved against the grain of the times I grew up in.’ The era was 1960s Germany; in that context, Baselitz feels he was subversively respectable. ‘For example, I never took any drugs. I have been a very faithful husband, I just wanted to hold on to my wife, I wasn’t interested in straying. I never went on any political demonstrations.’ His major offence, however, was not what he didn’t do but what he actually did: paint figurative pictures.

Eventually, fashions reversed, and this perverse behaviour made Baselitz a celebrated figure in the world of art. At 78, he remains vigorously productive. We were talking in White Cube, Bermondsey, the spacious galleries of which are filled by an exhibition of recent oils, watercolours and sculptures by Baselitz. Many of these feature the naked bodies of the artist himself and his wife Elke, dangling like wrinkled chrysalises or — since in company with so many images in Baselitz’s oeuvre they are upside down — like pallid bats. They seem to float, with visibly ageing anatomy, in a spectral void flecked with stray skeins and splodges of paint resembling distant stars. Perhaps — as the title, ‘Wir fahren aus’, or ‘We’re off’ suggests — Baselitz, as he approaches 80, is contemplating the end.

At the beginning, however, as he explained to me, Baselitz was attacked whenever he showed his work. Moreover, in addition to being outrageously reactionary, because his works were not abstract, he was also suspected of being upper class. ‘Some people assumed I was an aristocrat and called me “Von Baselitz”, which was terribly funny.’

In fact, Baselitz is not his real name — he was christened Hans-Georg Kern — but a pseudonym he adopted from his native village, Deutschbaselitz, a little place a few kilometres from Dresden. In 1945, at the age of seven, he saw the firestorm on the horizon and then the next day walked with his family through the smoking ashes of the city centre as they fled the approaching Red Army.

In reality, his background was middle class, his father was a teacher. ‘If I had really been aristocratic I would have had no chance whatsoever of being accepted. If you wanted to become a famous artist, the circumstances of your background had to be really bad.’ So, I suggest, Baselitz was an outsider, and maybe that was good for his art. And Baselitz — a big, jovial man — laughs and agrees. Mind you, there were other reasons why he ran into trouble in his early days.

Hanging on the wall behind Baselitz in the conference room at White Cube is an extremely graphic painting of the central section of a naked, overweight male body. It’s not one of his own works, but ‘Parts of Leigh Bowery’ (1992) — namely the thighs, paunch and genitalia — by Lucian Freud.

Like Freud, Baselitz has created images that caused a frisson of shock — in fact, more than a frisson on occasions. When two of his best-known early works were exhibited in Berlin in 1963, they were seized by the public prosecutor, and the artist was tried and fined. One of these, ‘Big Night Down the Drain’, depicted a dwarfish figure masturbating. When he began, Baselitz once told me, his work came from a feeling in his belly. ‘A certain defensive attitude; eruptive, vulgar.’

At first, he painted from his imagination, ‘more the way in which children would paint’. Then, in 1969, Baselitz began painting real images — figures, landscapes — but topsy-turvy. This was, as he explains it, also in part a defensive measure. ‘Because of the inversion nobody was interested any more in exactly what was depicted. Only when I did that did it free me for the first time to use shadow, use space, use realistic figures.’

In 1973, Baselitz went on, he took a Polaroid of himself and his wife Elke, naked. ‘I painted that, upside down, and I’ve been doing it ever since. I didn’t want to paint huge rhetorical paintings, battles and so forth, I wanted to remain within the zone of the intimate. Paint your wife, paint your friends. Art can be grand and imperial, like Michelangelo’s ‘David’. But it doesn’t affect my heart.’

So the pictures on view at White Cube are a further instalment in a highly unusual sequence, art historically: a depiction of happy monogamy, with both partners in the union starkers. It is not so uncommon, Baselitz points out, for uxorious artists to depict their partners in the nude, Rubens and Bonnard being two examples who come to mind. But to represent themselves and their spouse together in this way is far from common.

Stanley Spencer’s startling portraits from the 1930s of himself with Patricia Preece are one parallel, and it turns out — a little surprisingly — that Baselitz is interested in Spencer. In recent decades he has come to feel an affinity with a number of British artists.

‘I’ve known the work of Kossoff, Kitaj, Freud, Auerbach and all the artists from that school for a long time, but in the Seventies they didn’t interest me. What they were doing seemed obsolete then. I thought, “You can’t paint like that any more.” Maybe the rupture wasn’t so palpable here, but in Germany there was an incredible break between the old-fashioned forms of art and the avant-garde.’ Eventually, he changed his mind; nowadays he feels ‘close’ to the artists of the so-called School of London.

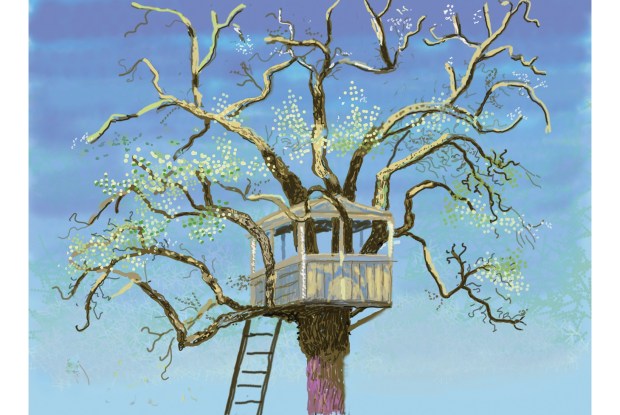

What all of them — Baselitz, his German contemporaries Gerhard Richter and Anselm Kiefer, and the Brits — have in common is that they carried on painting pictures of people and things during a period when many believed such an enterprise was over and out. A further giant — whose work Baselitz has admired since the Sixties — ‘wunderbar!’ — is David Hockney. He saw an exhibition of Hockney’s Yorkshire landscapes in Germany a few years ago, and was ‘really excited’ by it. ‘I thought this guy is really trying to push the boundaries and go in a new direction. He’s not resting on his laurels, he’s exploring fresh realms.’

Currently Baselitz is considering the question of ‘late style’, the notion, derived from 19th-century Germanic art theorising, that in old age painters may enter an exalted final phase. ‘It’s the central, most important thought preoccupying me all the time. Many artists — a few of whom have done excellent things — have produced miserable work at the end of their careers. I am trying to understand why otherwise good artists produced poor late work. Was it poverty, was it drugs, was it mental weakness? And how can I go against that, how can I move towards late pictures that are meaningful and powerful?’ That’s something major painters seem to have in common. Auerbach and Hockney are the same. The older they get, the harder they seem to try.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Georg Baselitz: Wir fahren aus (We’re off) is at White Cube Bermondsey until 3 July.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in