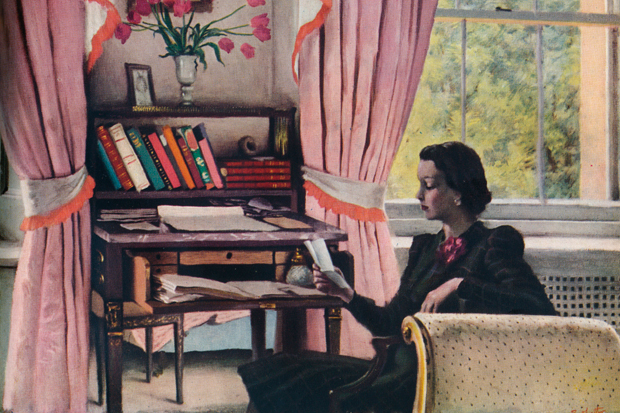

Not a single line of this highly distinctive memoir happens out of doors. All of it takes place in rooms: the dining-rooms and living-rooms, mainly, of five elderly, thin, Jewish bridge-playing ladies, Bette, Bea, Jackie, Rhoda and Roz, in a desirable suburb of New Haven, Connecticut. Their napkin rings are made of silver, porcelain, tortoiseshell, bamboo and Bakelite, and they put on their best necklaces and get out the best coffee cups when it’s their turn to host. They have met together to play bridge every Monday afternoon for over half a century. ‘Five ladies, luncheon of silvery fish, two decks of cards and a scoring pad nearby.’ (It’s five in the club, by the way, so there’s an extra if one of them is ill.)

The author Betsy Lerner, a New York literary agent in her fifties, is the daughter of Roz. Betsy has moved back to New Haven for her husband’s work purposes and lives too near her mother for comfort. She takes every comment her mother makes (such as that she ought to put paper hand-towels for guests in the bathroom) as a criticism of her whole existence. Therapy is needed, and she has it with a non-speaking therapist, who helps.

But she also clearly needs to write this memoir to sort things out. Having taken for granted those bridge afternoons as the wallpaper of her childhood, she has become fascinated by the ladies’ astonishingly regular, unruffled habits, including her mother’s. What have their long married lives really been like? Did they mind not having paid jobs? How come they never, ever hug each other? With her gentle probing of each of the ladies in turn, and her acute eye for telling detail, she draws us into the same fascination.

You don’t have to be a bridge-player to find this book enjoyable. I’m not and was dreading the endless dummies and no-bids and ‘Thank you, partner’s, but I just let them wash over me, and there aren’t too many of them. ‘Winning a hand is like shooting the rapids and outwitting a fox at the same time,’ Lerner tells us, and I’m sure it is, if you can face those long afternoons indoors, looking at the backs of other people’s hands. (One of the ladies has ‘knuckles like a horse’s knees protruding with age’.)

But it does help if you’re interested in old age. I guessed that the Bette Davis quote ‘Old age ain’t no place for sissies’ would find its way in, and it did; but this was redeemed by countless pinpoint observations. This is a thoughtful, affectionate study of a small slice of the generation of middle-class American women who married in the 1950s and 1960s. I found the stability and dignified privacy of their lives incredibly reassuring. They discuss theatre reviews, New Yorker articles, the weather and the weekend, but see no reason to ‘open up’ to each other in the way that our generation does. Lerner tells us:

Their unspoken commandments are ‘Thou shalt not pry. Thou shalt not reveal. Thou shalt not share.’

This makes it all but impossible for Betsy to find out the answers to her questions: any long-hidden pain comes out in very brief flashes. Bette, for example, was diagnosed with breast cancer

in the days when no one used the word ‘cancer’ and no one said the word ‘breast’.

But the flashes are worth waiting for.

The bridge ladies’ marriages were ‘built to last, like the appliances from their era’.They’re not keen on spontaneity, preferring events to be ‘in the calendar’, so they can prepare properly for them and do their nails. They keep their houses clean and tidy, even ‘folding the rags’. They take a long time to make lunch on bridge days and can’t understand how our generation can throw a meal together so quickly. And they are united in the belief that ‘the world was never this dangerous’.

They’re remarkably unemotional about each other, at least on the surface. When Betsy dares to ask what might happen when one of them dies, her mother replies: ‘The club won’t fall apart. We’d find someone to fill in.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in