A story John Piper liked to tell — and the one most told about him — is of a morning at Windsor presenting his watercolours of the castle to King George VI and the Queen. She admired his storm-tossed battlements; the King did not. ‘You seem to have had very bad luck with your weather, Mr Piper.’ If this was a criticism of the artist’s gloomy and gothic tendency, it was an unfair one. Mr Piper was very unlucky with his weather.

In Caernarvonshire in 1945, on a sketching trip with two small children in tow, it never stopped drizzling. In 1946, on another family sketching holiday in Pentre, his wife, the librettist Myfanwy Piper, wrote grimly to a friend: ‘JP is doing a drawing in a churchyard in a howling wind and both children and I are in the car and they are either shaking or shouting or asking me for a pencil or paper or hurling insults at each other and its frantic and my feet are cold.’

In 1975, Piper travelled to Chichester to paint the cathedral for a book to celebrate the 900th anniversary of its foundation. The Dean, Walter Hussey, was particularly grateful given the ‘appalling’ weather conditions that met Piper’s arrival. King George might have minded the sturm-und-drang of Piper’s art, but in Hussey Piper found a sympathetic patron.

In 1964, Hussey and Piper had collaborated on a project for the High Altar at Chichester. Piper suggested a tapestry, a medium he had never tried before. His cartoons for the tapestry — ‘very early and immature sketches’, Piper apologised to Hussey, ‘scribbles on the back of an envelope’ — are among the exhibits at John Piper: The Fabric of Modernism at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester. It is an invigorating show, dashing colourfully through Piper’s textiles, tapestries, church vestments, silk scarves and woolpile rugs with great brio.

The tapestry cartoons show Piper’s process of working-out: overcoming the challenge of how to abstract the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit and the four evangelists, and mastering an unfamiliar medium. He played with collages of cut marbled papers, studied the tapestries of the Renaissance ‘to see how they had managed it’, and marvelled at the expertise of the weavers at the Pinton workshop at Felletin. There’s a glorious photo in the catalogue (superbly illustrated and a joy to read, edited by Simon Martin and Frances Spalding) of the doughy housewives of Felletin inspecting the completed Chichester tapestry laid out in the town square.

For the tapestries proper, it’s five minutes from Pallant to the Cathedral. If you approach through Dean’s Close you’ll stand on the spot where Piper painted in such appalling weather. Hussey was delighted with the tapestries, but one of the canons wore dark glasses to services in protest.

For Hussey Piper also designed a chasuble in yellow Thai silk and yellow satin with psychedelic spirals in appliqué gold kid leather. It was 1962 and it’s a very groovy vestment.

In the same year, and in more sombre mood, Piper produced a fabric design for Sanderson’s: ‘Stones of Bath’, printed on the firm’s Sanderlin fabric, a satinised linen which gave the designs a shimmering, restless texture. It was ideally suited to Piper’s designs for scudding clouds over Snowdonia (‘The Glyders’ fabric, 1960); the rippling, restless waters of the Grand Canal in Venice (‘Chiesa Della Salute’, 1960); and the play of light on Bath stone as in ‘Stones of Bath’. The Pipers had ‘The Glyders’ made into loose covers for the chairs at their home Fawley Bottom — ‘Fawley Bum’, John Betjeman called it.

Piper, who with Betjeman was a keen church-haunter, turned the foliate heads of medieval church bosses into patterns for silk scarves. These ‘Green Men’ turn up again as a set of ‘Four Seasons’ tapestries for the Royal Surrey County Hospital (1986). Winter is particularly appealing with his walrus moustache of ivy above holly-berry lips.

At the Fine Arts Society exhibition Counterpoint II: Modern Realism 1910–1950, there is more Piper, here painting a beach scene on an evening mild enough to sketch with the window open. Collaged curtains made of paper doilies blow in the breeze. In ‘The Harbour at Night’ (1933), an old tobacco packet — ‘Superfine Shagg’ — becomes an advertisement hoarding on the seafront. The sea is silver paper.

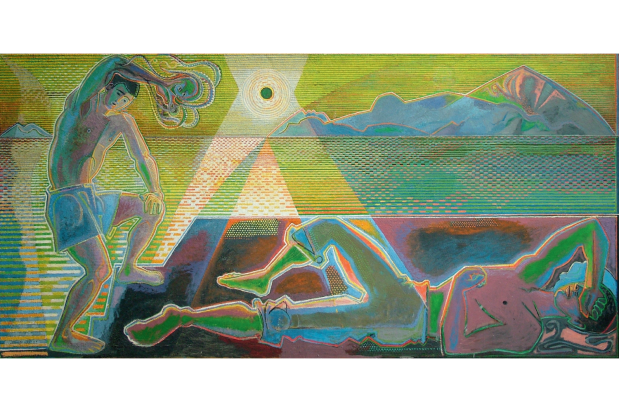

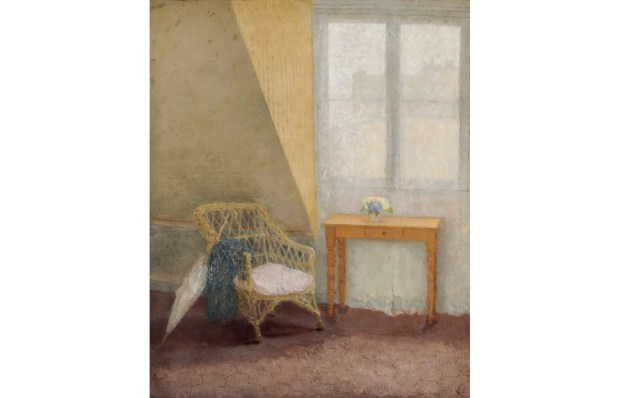

Counterpoint tackles the accepted notion that the story of modern art in Britain is one of an insistent ‘journey towards abstraction’. In the 1930s, Piper rejected the muscular abstraction of Ben Nicholson, as did many others. Here we find Stanley Spencer, C.R.W. Nevinson, Edward Wadsworth and John Duncan Fergusson in bright, holiday spirits at Cookham Regatta, Cap d’Antibes, and the quay at Dinard, and William Nicholson and Christopher Wood in raptures over freesias, primulas and mimosa. Eric Ravilious, meanwhile, has just the solution to dreary British rain: a submarine, sketched at the Admiralty base at Gosport, and perfectly watertight.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in