By now, Labour should be rather good at post-defeat inquests. Plenty have been conducted over the years and the drill has become familiar. The party goes into an election promising a certain vision of the future only to find out that it leaves the voters cold. A senior figure is then commissioned to state the obvious, and the report is sent back to the leader’s office, where it is filed and ignored. Then the party embarks upon a fresh misadventure — and the cycle of defeat begins again.

This week Labour is digesting its worst result in Scotland since 1918, having lost not only to the nationalists but to the Tories. In England’s council elections, Labour lost 18 more seats than it gained, which sounds like fairly decent damage limitation — until you remember that no opposition has lost seats mid-term since the 1980s. In Wales, Labour saw Ukip hoover up the working-class protest vote. Only Sadiq Khan’s election as London mayor made last week’s election day less than calamitous. And even this drove several Labour MPs to despair, because it meant the overall results were not quite bad enough to prompt Jeremy Corbyn’s resignation.

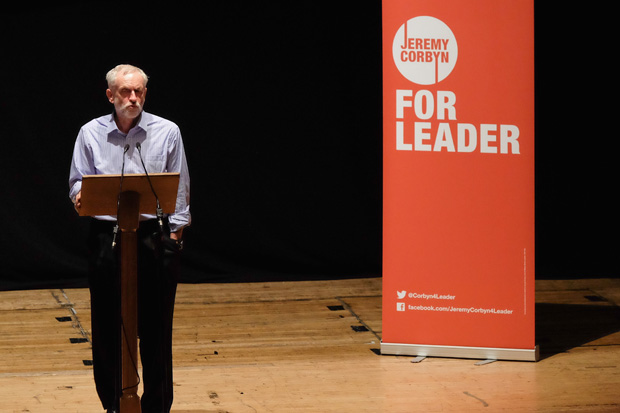

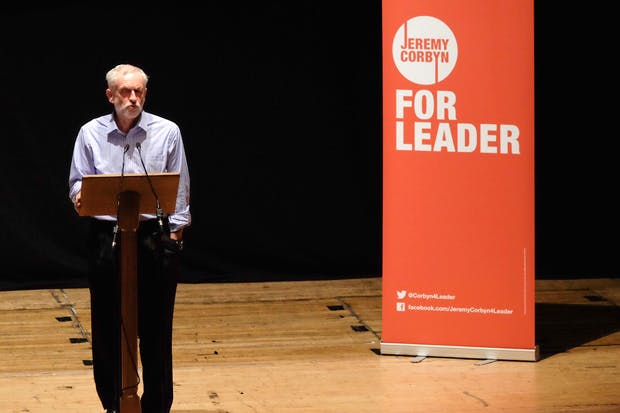

To his credit, Corbyn did admit to a meeting of Labour MPs on Monday that the party needed to do better. But he still seemed keen to lay at least some of the blame on those who have had the temerity to mention the electoral iceberg that he is steering them towards. A number of moderate Labour MPs are sharing their own analysis, pointing out that the party has increased support in areas it already holds, with only one in seven gains in seats it needs to win for the general elections. By contrast, nearly half of the losses were in the key areas where Labour needs to make gains (Great Yarmouth, Thurrock, Plymouth and Southampton).

Labour also lost three council seats to the Tories in Nuneaton — which has, since election night, been seen as the party’s bellwether seat. Greenberg Quinlan Rosner, a political consultancy, held focus groups there at the end of April and found voters telling Labour to get a new leader because Corbyn was ‘scruffy’ and they couldn’t imagine him visiting the White House — he’d look ‘like someone who got lost from the tour’.

But even armed with such dispiriting analyses, Labour MPs who had been planning a coup against Corbyn have now called it off. One senior rebel puts it simply: ‘He’s too weak to win but too strong to remove, and that’s our big problem.’ Another Labour plotter says: ‘I’m hoping all the time that something is going to happen to save the Labour party. I was hoping that if we did lose loads of seats, that might be something to capitalise on and might create the impetus. But I now think it’s pretty unlikely anything will happen after the referendum’.

Tom Watson, Corbyn’s deputy, was quick to dampen down any talk of a coup last week: rebels think they need his tacit support at the very least if they are to oust the leader. A quick vote on Trident after the referendum and the publication of the Chilcot report on 6 July will make what seemed like the ideal time to move against the leader much more difficult. David Cameron would find it fairly easy to make political capital when Chilcot is published, but nowadays it’s never too hard for the Tories to make capital at Labour’s expense. Other Labour MPs grumble that there is never a good time to remove a leader.

A minority of Labour rebels think even a failed coup would have its uses, by forcing the party to have a proper argument about its future (or lack thereof). But the moderates are still working out how to understand the vastly expanded Labour membership. At some point, they argue, the new members will realise that Corbyn is not the messiah and that the popular political movement they expect him to create has not been delayed: it is never going to turn up.

No one is expecting a Labour revival in Scotland any time soon — indeed, the party seems set to learn the wrong lesson from its latest humiliation. Kezia Dugdale wobbled all over the place on the question of independence during the Holyrood ampaign, while Ruth Davidson’s Tories pitched themselves as the clear, unambiguous unionist choice. Scottish Labour tried to be a boring version of the nationalists, and this flirting with nationalism helped the SNP grow even stronger. In this way, Scottish devolution, designed as a trap for the Scottish Tories, has ended up ensnaring Labour.

Dugdale will stay as leader; Scottish Labour is running out of people to put at the helm of its party and her mission always did look hopeless. As for the SNP, it has now lost its majority in the Scottish parliament — diminishing the chances of Nicola Sturgeon calling another independence referendum. Sturgeon, for her part, danced around the issue in the SNP manifesto and in her victory speech last week focused as much on issues such as education as she did on independence. Some in Labour worry that their party may be trying to sound more nationalist just as Scotland has passed the high water mark of nationalism. And when the Scottish Tories under Ruth Davidson are reaping a Unionist dividend.

All of this means that Labour is now fighting different battles in different parts of the UK: Nicola Sturgeon’s SNP, the Tories in the English boroughs and Ukip in Wales. The party’s ongoing collapse in Scotland has made it all the less likely that it could win a general election in 2020.

Labour will say, as it always does, that it has listened and learned. But the only true sign that is has learned anything will be the election of a new leader — a prospect that looks even more distant now than it did six months ago. Lucky old Cameron.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in