‘In the end, nothing goes with anything,’ Lucian Freud remarked one afternoon years ago. ‘It’s your taste that puts things together.’ He would perhaps have been a little startled to find those words inscribed on the wall of Painters’ Paintings at the National Gallery, but they are very apt.

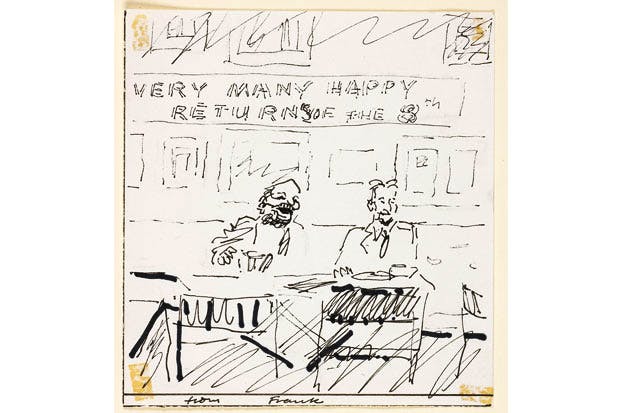

The exhibition reassembles the works of art owned by a number of great painters, among them Van Dyck, Reynolds, Degas, Matisse and Freud himself. It begins with pictures and sculptures that used to co-exist in Lucian’s sitting-room. Most powerful of these is a magnificent Corot, ‘Italian Woman’ (c.1870), that once hung over his fireplace and is now part of the National Gallery’s collection. Around are a small Cézanne, an Auerbach drawing, a Degas bronze and a portrait by John Constable. A series of items, that is to say, which do not have a great deal in common, except the common factor: Freud.

As you look at them, you can see how he found parts of himself in each — the jokiness of the little Auerbach, the intimacy of Degas’s head of a resting woman, the formidable presence of the Corot. Furthermore, you can see these all in relation to his own works, hung side by side in the show. The effect is just the same when you step next door into the room devoted to Matisse and his array of pictures by Picasso, Gauguin, and Cézanne, all revealing. I hadn’t realised Matisse once had Degas’s ‘Combing the Hair’ (c.1896), for instance, its space entirely created by deep orange-red hues just as happens in his own ‘Red Studio’. Similarly, in the two splendid galleries devoted to Degas you encounter different aspects of his own complex artistic personality: the loose brushwork of his friend Manet; the imperious precision of Ingres.

Part of the pleasure of the show — itself excellently put together by the curator Anne Robbins — is seeing how these artists selected their own artistic company from past and present. Another game is guessing what each wouldn’t have fancied of the other’s cherished possessions.

Freud, for example, would have loved to have Van Dyck’s Titian, but he’d probably have said ‘no thanks’ to Joshua Reynolds’s Poussin if it had been offered as a gift; Degas on the other hand might have been keen on that one. One further conclusion is how naturally Lucian fits into this company. It is just under five years since he died and already he looks like an old master.

Of course, for nearly two-and-a-half centuries the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition has been demonstrating the truth of the dictum that in the end nothing goes with anything (the current edition is number 248). It is always a cheery jumble, partly because there is no one person truly in charge. However, each year someone tries. This time the coordinator is Richard Wilson, a brilliant exponent of sculptural installation who has for example transformed a room at the Saatchi Gallery into a sinister lake of black oil that has long been one of the sights of London.

He starts off the show with a work in just this spirit — the everyday transformed into something rich and strange — by the American duo Allora and Calzadilla. It is a petrified petrol pump, as if a filling station had been excavated from the ruins of Pompeii. Surrounding it and elsewhere in the exhibition are other works by art duos, including a very large, very good Gilbert and George (the first time I have seen any of their works in Burlington House). A whole gallery is devoted to photographs by the German artists Bernd and Hilla Becher, who spent their careers taking carefully neutral black-and-white shots of antiquated central European industrial buildings.

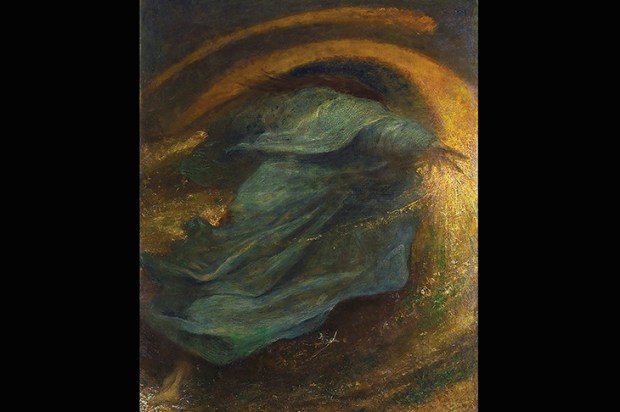

So in some places there are traces of a individual sensibility, Wilson’s and those of the academicians responsible for hanging particular rooms. But some law applies to such things — possibly that of entropy — so when order is created in one corner of the RA, primordial muddle asserts itself elsewhere. Amid the confusion, as always, there are outstanding things scattered here and there. At one end of the grand central gallery, for example, there is an oil-cum-assemblage by Anselm Kiefer, ‘Böse Blumen’, or ‘Evil Flowers’, flanked by a fine sombre abstraction by Sean Scully and a euphoric one by Frank Bowling — all adding up to a bravura demonstration of the continuing power of paint.

It’s no surprise that the Summer Exhibition is a bit of a jumble. What struck me, on looking at it shortly after the new galleries at Tate Modern, was how similar these are. They even have some of the same ingredients — there is a room of the Becher’s photographs at Bankside too — but of the two jumbles the RA’s is distinctly more fun. Now that really is a surprising twist.

The post Jumbled up appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in