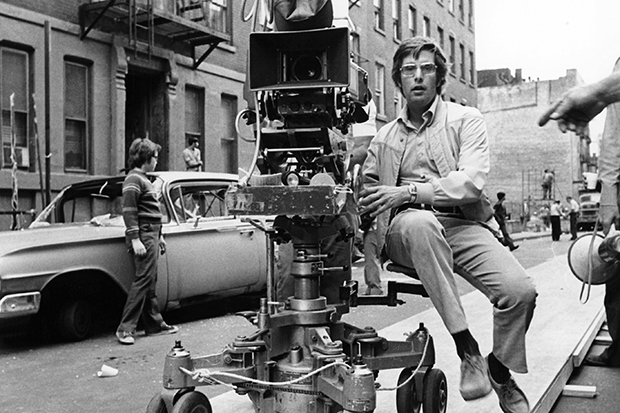

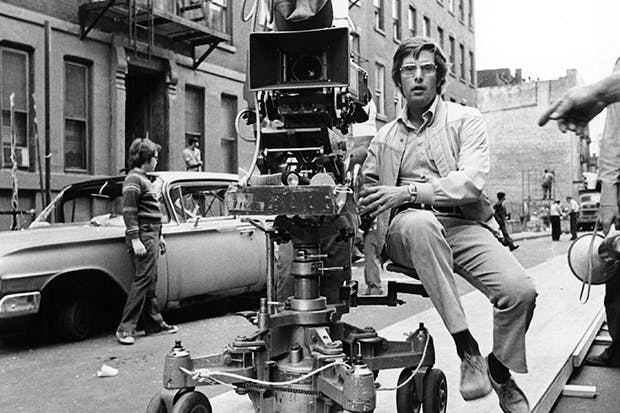

From the Oscar winning classics of the early Seventies — The French Connection (1971) and The Exorcist (1973) — to the southern trailer trash noir Killer Joe (2011), William Friedkin has been behind some of the darkest films ever to come out of Hollywood. He has also had a famously bumpy career, careening from great successes to big flops (does anyone remember Jade?). Somehow, he’s always rebounded. Currently, the 80 year old director is developing Killer Joe into a television series, set to star Nicholas Cage as the cowboy hat wearing detective/hitman played so mesmerisingly in the film by Matthew McConaughey.

At the Cannes Film Festival in May, Friedkin was basking in the sort of adoration he hadn’t known for half a lifetime. The man who reinvented the chase scene and showed how pea soup, under the right circumstances, can be the most frightening substance in the universe, was one of the festival’s most prominent guests, dropping in to present restored versions of his films and to give the annual masterclass.

In a dark blue suit and a pinstripe shirt, Friedkin is sitting in a leather chair under this year’s festival poster, an ethereal looking still from the finale of Godard’s Le Mépris that shows a man ascending majestic steps overlooking the Mediterranean. ‘I’m happy to present the films,’ he tells me. ‘And I’m happy that anyone still wants to see them, but I can’t watch them. I’ve seen all of these films maybe a thousand times. They no longer have any allure for me.’ Friedkin tiptoes out of the theatre before the movies begin.

He regrets, however, not having time to check out the other films. ‘The only way I would get to see the films is if I served on a jury. And I would never do that. Never. Because I don’t know that one film is better than another. People who run the track or race horses or tennis or boxing — they’re in competition. I’m not in competition with some guy from Iran or Uruguay.’

That afternoon I catch Friedkin joking that the screening of his 1985 film To Live and Die in L.A. will be empty. While his French handlers seem nervous, not quite catching on to the self deprecating humour, Friedkin himself is laughing like an endearing, somewhat crazy uncle. I found myself thinking: is this the guy who made The Exorcist? ‘You need to have a sense of humour,’ he says. ‘Otherwise you’d go absolutely crazy.’

The second film Friedkin presented at the festival is his personal favourite, Sorcerer (1977). Its producers must have had a sense of humour: Friedkin’s fresh take on Henri Georges Clouzot’s 1953 classic Wages of Fear was shot in five different countries, went way over its projected $15 million budget (an unheard of sum for a movie at the time) and faced numerous setbacks due to injury and disease (Friedkin caught malaria). To top it all, the film was a commercial and critical flop, savaged for being too dark, too complex and too inaccessible.

Sorcerer is often seen as sounding the death knell of American auteur cinema, along with box office fiascos by the decade’s other big indie directors, Martin Scorsese (1977’s New York, New York), Michael Cimino (1982’s Heaven’s Gate) and Francis Ford Coppola (1981’s One From the Heart). Most think that’s how the wild Easy Rider generation of American directors came to a screeching halt in the early 1980s. Friedkin disagrees.

‘I don’t think [Sorcerer] had anything whatever to do with it,’ he tells me, adjusting his aviator shades. ‘The major studios in Hollywood could not allow so called auteurs to take over the industry. The owners and managers of the studios demanded control. And what my generation did was we took the controls because they didn’t know the audience and we did at the time.’

Then came a little film called Star Wars, directed by George Lucas and released the same year as Sorcerer — its aftermath was the franchising of Hollywood movies that continues unabated to this day. Friedkin clearly has a distaste for this stuff, but he’s not bitter. ‘The films being made today are seen by the widest audiences ever. But they’re not for me,’ he explains, adding that he’d rather rewatch Citizen Kane, The Verdict or MGM musicals.

The Seventies was a decade when Hollywood was churning out sophisticated adult fare with the regularity that it now makes films about men in underwear and capes. In Friedkin’s view, the end of auteur cinema in America wasn’t about the fortunes of individual films such as Sorcerer, but a systemic choice by the studios to reap the sort of profits that were hitherto only dreamed of. Sure, films like Network, Chinatown, Taxi Driver and Deliverance were all box office hits, but nothing close to the hundreds of millions that Star Wars generated (and continues to generate).

In 2013, Friedkin won a lawsuit against Paramount and Universal for ownership of Sorcerer, rescuing it from a legal limbo that had made it impossible for him to screen it. He also supervised the digital remastering that has since been made available on Blu ray. Seeing the film as the director originally intended (rather than the poor quality VHS that was the only way to access it for decades) has helped this brutally intense, utterly unique movie to emerge from both the critical slamming and from the shadow cast by Wages of Fear.

For his part, Friedkin doesn’t consider Sorcerer a remake at all. ‘I love the film by Henri Georges Clouzot, but I never set out to imitate it. I love the story. I think the story was kind of vital, about four strangers at odds with each other, but if they didn’t co operate they would all die — and the whole idea of no matter how hard you strive, we all end up the same way. And all that is in that story.’ While he’s glad to see Sorcerer finding an appreciative audience today, he remains somewhat uncertain whether a film he made out of personal conviction could gain a following. ‘I never thought any of my films would find a large audience. Never occurred to me. Especially the ones that were the most successful,’ he says with a shrug.

The following day, Friedkin addressed the packed house that had turned out for the festival masterclass. In the course of the interview, the French critic Michel Ciment made several references to the ‘commercial failures’ of the director’s career. ‘Look, Michel, I didn’t come here to be insulted,’ he countered, jokily.

‘Inside of every one of us who has ever created anything there is an almost constant record of failure,’ he told the festival audience. ‘That’s what we think about. That’s what involves our thought process. I know some of the most successful film makers and songwriters, and inside these giant talents is a little mouse.’ In Friedkin’s case, the mouse hasn’t stopped roaring for more than half a century.

The post Death of the auteur appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in