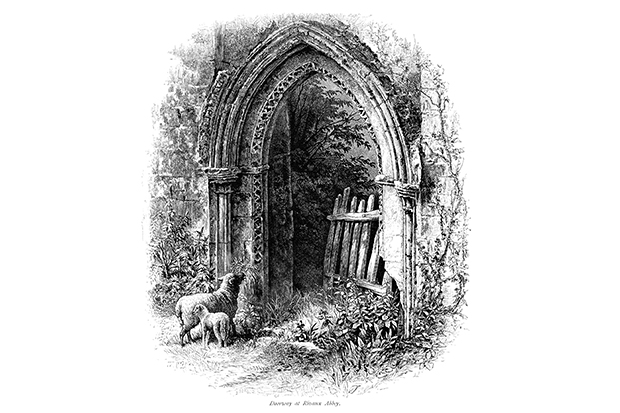

We’re so used to looking at the abbeys smashed up by Henry VIII — particularly Rievaulx and Byland, in north Yorkshire — that we forget quite how odd they are.

It’s not just that they’ve been preserved as ruins for 500 years, although that’s odd enough in a country that’s only saved ruins properly for a century. What’s odder is that these vast structures were built in such remote spots. It’s like finding a ruined Westminster Abbey in the middle of nowhere. When the Cistercians left Clairvaux in Burgundy, they were so desperate for peace that they came all the way north to found Rievaulx in 1132, and Byland a few years later.

For 400 years, before the abbeys were smashed, they were the biggest buildings for miles, with vast flocks of monks and lay brothers. And yet the valleys around remained deserted. Today, Byland and Rievaulx are still tiny settlements. I lay in the evening sun and stared at Rievaulx’s ruins for an hour without hearing a single car. Only the swifts and pigeons broke the silence. No mobile signal either — irritating when you want to muck about on the internet; heaven when you’re channelling Cistercian calm.

We had Rievaulx to ourselves that evening because we were staying in the old caretaker’s cottage, built out of the ruined abbey’s stone, which gives you access to the abbey after closing. That emptiness is a gift in the busy summer season; even busier, now there’s a visitors’ centre and a small stylish museum. The museum’s star feature is a 13th-century Christ in Majesty sculpture, his head chopped off by iconoclasts, leaving a decapitated Christ in a crisply carved belted gown. The Abbey Inn in Byland — also built out of the abbey’s stone — doesn’t offer after-hours access to the ruins. But the Mouseman bedroom does give a head-on view of the great butchered half-circle of Byland’s rose window. Once again, I stared and stared.

Why are ruins so hypnotic? The conventional wisdom is that the joy of ruins is a human construct, created by Sir John Vanbrugh when he tried to preserve the ruins of Woodstock Manor as a charming eye-catcher at Blenheim Palace. That silly old modernist, the Duchess of Marlborough, ignored him and knocked it down in 1720.

I’m not sure the conventional wisdom is right. There’s an innate pleasure in seeing pure blue sky through Rievaulx’s empty windows, once filled with mullions, transoms and glass. There’s a thrilling horror at Henry VIII’s monstrosity when you see Rievaulx’s fother — a chunk of lead, shaped like a mammoth bar of soap, formed from the abbey’s melted roof. The fire to melt the lead was fed by burning medieval choir stalls. And there’s a pleasing game in filling the ruins’ gaps by extrapolating from the fragments. At Byland, you can still see bits of the monks’ stone choir stalls, and the partitioned corners of the cloisters where they illuminated their manuscripts. Suddenly, the ghosts of medieval England are heart-stoppingly close.

The post Bare ruined choirs appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in