Sicily

Under the watchful eye of Mount Etna the storied past of the island lies parched and yellowish, but as one gets nearer to the fiery growling giant the air turns cool, the sun glistening against black volcanic rock. Sicily is of two minds. Orange groves and beaches galore, then dank forests and the possibility of lava flows. Sicily’s history resembles its landscape: peaceful and religious; violent and vengeful.

I first sailed to Taormina back in the Sixties, visited the ancient Greek amphitheatre and listened to Dvorak’s New World Symphony while breathing in the smells of history. It was an extraordinary spectacle: beautifully dressed people, a great Italian symphony orchestra and a sunset that illuminated the ancient site and brought to life its legends as it has for thousands of years. It was as romantic as it gets, and then some.

Back in 415 BC, the Athenian patrician Alcibiades pulled a number that signalled the end of Athenian hegemony. Alcibiades had a vision of the conquest of Syracuse and the foundation of a new empire of the west. Bogged down in a war of attrition with Sparta, the Athenians did a Bush-Blair by invading Sicily. A vast armada was annihilated, as was the Athenian imperial mission. End of story — for Athens, that is.

I’ve often thought of Alcibiades, and the Greeks landing in Sicily with the conquest of Carthage in mind. I’ve sailed through Scylla and Charybdis, the Strait of Messina, countless times, and had a knockdown once, just as we were halfway between the two Homeric monsters. Sicily might not be good for Greek sailors, but oh, what a past. We once stopped to visit Prince Galvano Lanza, whose name features in The Leopard, and his staff were on strike. He lay in his palazzo, immobile, a 1,000-year weariness etched on his face, reading about Napoleon. The staff eventually obliged and even put on their finest. Princes and servants, violence and ritual, Church and no state; that’s Sicily for you.

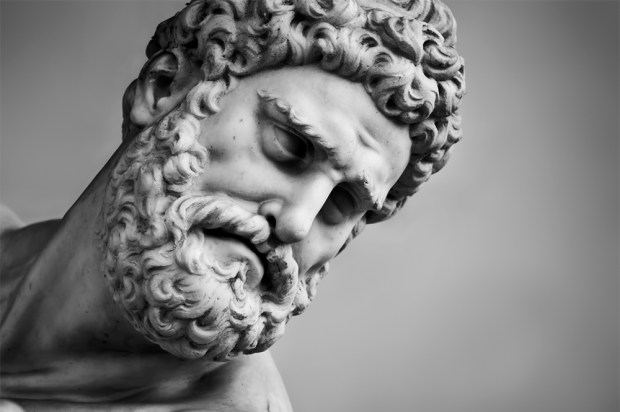

Speaking of Il Gattopardo, Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s lyrical lament for a disappearing world, and one of the greatest post-war European novels, the protagonist, Fabrizio, Prince of Salina, is probably my favourite fictional hero. An excellent horseman, a terrific shot, a tireless womaniser, Fabrizio is brave, intelligent, wise, a sinner, yet a loving family man with a very generous heart. He is a great aristocrat who understands the vulgarity of the upwardly-mobile middle classes and new money.

As everyone except Kanye West, the Kardashians and others of their ilk knows, the novel opens in 1860, with Garibaldi and his troops landing in Sicily and the Risorgimento beginning in earnest. Landowning aristocrats and peasant tenants are in confusion, the contract between them undermined by various unfamiliar forces, political liberalism and a rising middle class. The prince takes it all in his stride. He understands his own coming irrelevance, daydreams of past — and future — lovers, and remains conservative and mystical about his lands and his position.

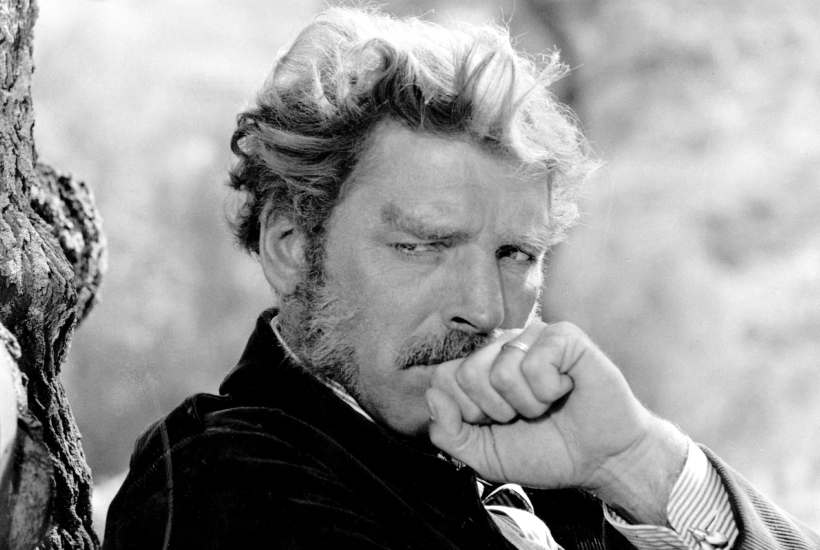

Unlike other films of great books, the one based on The Leopard, directed by an aristocrat of Fabrizio’s ilk, Luchino Visconti, is equal to the novel. Visconti told a friend of mine that the one great riddle of his life was how an acrobat born and raised in the Bronx could play the Prince of Salina as if he were Lampedusa himself. This was Burt Lancaster in the 1963 movie — probably the best film ever made. One feels the prince’s pain as modernity approaches but he never expresses it. He watches the young dancing at the great ball at the end, and the yearning for his long-gone youth is evident only in his eyes.

He’s still handsome and leonine and when his nephew’s betrothed asks him to dance, the scene remains ambiguous. Does he, as seems certain, desire her, or is it simply an avuncular feeling? The strength of the story is that the physical details reveal the soul. The pomp and finery are superb, and the bon mots are as relevant today as they were back then: ‘If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.’

‘The Sicilians think themselves perfect,’ thinks the prince. He tries to shock his priest, raises his eyebrows when his wife crosses herself when he appears naked in front of her, and genuflects religiously as he walks home after the ball looking at the stars. The novel ends in 1910, following the prince’s death in 1883. The Latin dismissal of women is there for everyone to see: the prince’s daughters all end up old maids, unhappy and unfulfilled, full of regrets and memories of what might have been.

Lampedusa died in 1957, and The Leopard was published posthumously. It was his only book, although a few short things have surfaced since. But nothing to compare with Il Gattopardo. His palace in Palermo had been destroyed by Allied bombs, and he had served his country in both world wars. Lung cancer killed him at 60 years of age.

Sicily is brown and haunting, with beautiful old houses and rubbish everywhere, violence always just around the corner, as well as poetry and mournful song. The architecture is splendid, the graffiti less so. I am here to party for four days and nights without respite. I feel a bit like the prince, enjoying the present but hankering for the past.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in