Do you ever tell your pupils that debt is a bad thing?’ I challenged the headmaster of a thriving Midlands prep school.

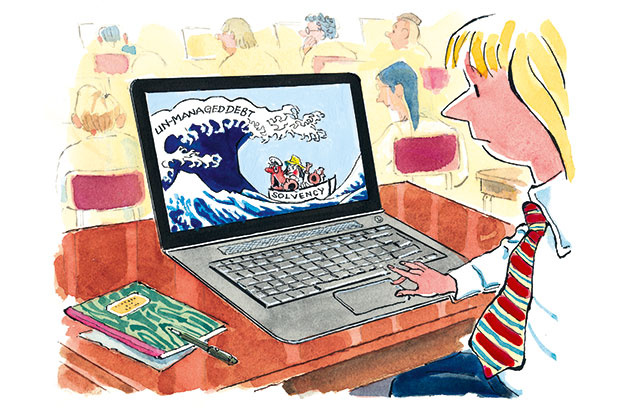

His answer was more nuanced than I was expecting — but since independent school heads are also educational entrepreneurs these days, perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised. ‘I’d be anxious about too much moralising in this area. Actually a lot of our pupils’ parents are business owners, for whom debt can be a good thing when it allows their businesses to grow. But we do try to teach the older ones that debt always has to be managed, and to ensure that our 13-year-olds leave here with some financial savvy.’

The teaching of personal finance in schools is by no means new, but it has moved up the agenda in recent years as part of the ‘economic’ element of ‘Personal, Social, Health and Economic Education’ in the national curriculum. That places it alongside all the stuff about respecting gender differences, staying safe on social media and avoiding radicalisation.

But precisely how finance should be taught, at what age — and with how much moralising attached — are open questions. Like the answer to where babies come from, discussion of where money comes from and where it goes used to be seen as a parental responsibility, rather than a task for teachers. In today’s climate of financial irresponsibility — in which kids are bombarded with commercial temptation even before they learn to add, never mind calculate compound interest on payday loans — it must be a good thing for schools to offer a basic framework of knowledge about how money works. For older pupils, it must be an even better thing to interest them in how money can work creatively through entrepreneurship and investment.

At the primary level, money offers a colourful way of teaching arithmetic, as in how many 30p apples can you buy for a pound and how much change you should receive (though ‘change’ may become alien to a generation that will shop only with contactless debit cards). For the 11–14 age group, it gets a bit more interesting — and one tool very widely used, having reached two thirds of English secondary schools and 1.4 million pupils by July last year, is ‘LifeSkills’, a package of teaching materials offered by Barclays. This covers employability issues, such as how to present yourself for a job interview, as well as ‘importance of personal budgeting’, ‘managing financial risk’, ‘saving towards financial independence’ and ‘personal responsibility in relation to money’.

Interestingly, LifeSkills head Kirstie Mackey does not absolve parents from trying to drum these themes into their teenagers. Among her ‘five top tips’ is: ‘Warn them of the danger of short fixes… It’s important to teach your child that credit cards are not free money: far from it. If you lend them money it’s a good idea to explain that, not only will they need to pay you back in full, but they’ll also need to pay off any interest in chores.’

All this is valuable if it gives youngsters a grasp of what financial obligation means, and how to stretch limited resources over a term or a year. It’s also good if it teaches them not to fear manageable debt: otherwise they may be put off university by an irrational horror of student loans, which in reality are a burden that will swiftly diminish as they advance through life.

Closer to the priorities of teenage life, one of the first challenges they’re likely to encounter is the small print of a mobile-phone contract — and it’s better to understand such risks in advance than to be in the position of one Eton pupil I know who, having racked up a £400 bill, was ordered by his father to trudge London’s pavements until he found a part-time job to pay it off.

But can teenagers really take in financial concepts that go beyond these immediate life lessons? The head of ‘guidance’ at a leading public school offers the opinion that scarce classroom time is better spent securing good A-level grades that will secure good university places, leading to good jobs with rising salaries. He recalls that a posh City investment firm was once invited to deliver a seminar to his final-year group on their lifetime potential for earning and saving, with a view to a comfortable retirement. But ‘it wasn’t particularly arresting for them. It all seemed too far away: they were much more focused on where they were going for their gap years.’

For a quick guide to what matters for school-leavers, he recommends pupils view a short YouTube video on student finance by the University of East Anglia, or better still, the ‘students’ section of the Money-SavingExpert website — which includes, for example, a comparison of ‘best buy’ student bank accounts with perks attached. Would you rather have a free railcard, an Amazon voucher, a zero per cent overdraft or an account with a bank that has ethical lending principles? Adult life will be full of such difficult questions, and it’s good that schools are trying to equip our kids to answer them.

The post Lessons in lolly appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in