In debates about what should and should not be taught in art school, the subject of survival skills almost never comes up. Yet the Dutch, who more or less invented the art market, were already aware of its importance in the 17th century. In his Introduction to the Academy of Painting (1678), Samuel van Hoogstraten included a chapter headed ‘How an Artist Should Conduct Himself in the Face of Fortune’s Blows’. Top of his casualty list of artists ‘murdered by poverty …because of the one-sidedness of supposed art connoisseurs’ was the landscape painter and printmaker Hercules Segers (c.1589–1633).

This year, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam has mounted three shows devoted to Dutch artists who failed to strike gold in the Golden Age, of whom Segers is the most extreme example. ‘No one wanted to look at his works in his lifetime,’ Van Hoogstraten tells us, and entering his first full retrospective in the museum’s Philips Wing, you can understand why.

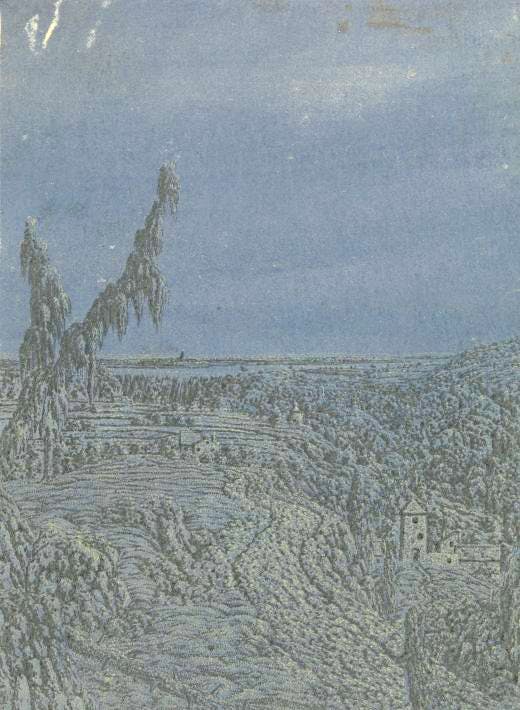

‘Road Skirting the Plateau, a River in the Distance’, (c.1615–30), by Hercules Segers. Photo: Rijksmuseum

Segers was at least two centuries ahead of his time. True, his landscape paintings fit within the Netherlandish tradition, despite stretching the possibilities of the panoramic vista almost to breaking point with their mountain valleys crisscrossed by fenced fields and their rivers winding into infinity. He was not the only flatlander to dream of mountains, Mediterranean light and cypress trees; the difference was that unlike his Dutch Italianate peers he never seems to have travelled further than Brussels. But that was no bar to an imagination described by Van Hoogstraten as ‘pregnant with whole provinces, giving birth to them with immeasurable spaces’.

If Segers’s paintings were original, his prints were radical. The commercial advantages of the multiple were apparently lost on him — although he worked in series, no two prints of his are alike. With their different-coloured grounds and overpainting in oils, the eight versions of his ‘Distant View with a Road and Mossy Branches’ (c.1615–30) are like night and day. In experimenting with what Van Hoogstraten called ‘printed paintings’ he effectively invented the monoprint. He also developed the sugar-lift etching technique and was the first western printmaker to use Japanese paper.

Necessity was sometimes the mother of his inventions, as when he printed on the marital bed sheets, to the horror of his wife. But it was his artistic vision that was truly revolutionary: his fantasy landscapes of crumbling crags and wrinkled lava flows are simply not of this world. Where did they spring from? Their corrugated contours seem to mimic the structures of corals, shells and sponges that he may have seen in contemporary cabinets of curiosity. Some look like rubbings, prefiguring the frottage drawings of Max Ernst — probably no coincidence, as the prints so little valued by Segers’s contemporaries that they were used for wrapping butter and soap would become all the rage among the surrealists.

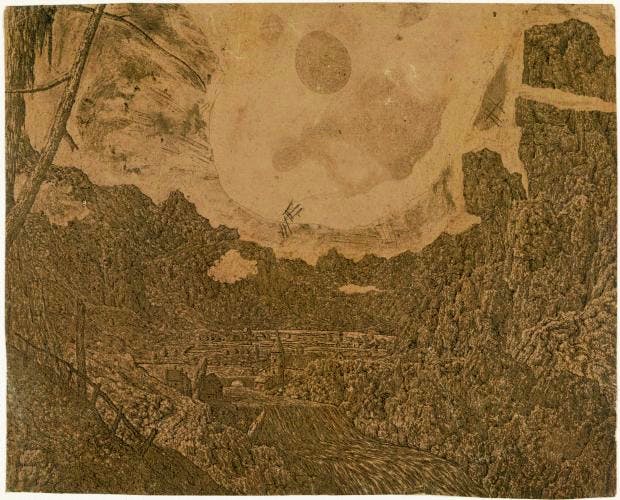

‘The Two Trees (An Alder and an Ash)’, c. 1625–1630, by Hercules Segers. Lift-ground etching. Photo: Rijksmuseum

Segers was always an artist’s artist. When he was forced by debt to sell up in Amsterdam in 1631 and move to Utrecht, eight of his paintings were bought by Rembrandt, who later acquired the original copper plate of his ‘Tobias and the Angel’, burnished out the figures — and the massive fish — and appropriated the landscape for his own ‘Flight into Egypt’. The two versions hang side-by-side in the exhibition. This was possibly one of the last prints Segers made. At some point in the 1630s, in despair over his family’s abject poverty, he went out and got drunk — a state to which Van Hoogstraten assures us he was unaccustomed — fell down the stairs and died.

In the other half of the Philips Wing the Rijksmuseum is staging another first: an exhibition of Brazilian animal drawings by Frans Post (1612–80) that have never been seen in public before. In 1636 the 23-year-old Post travelled to Brazil with Johan Maurits of Nassau, newly appointed governor of the Dutch Republic’s short-lived Brazilian colony, to record the landscape and its flora and fauna. While there he painted topographical views and detailed watercolours documenting the workings of sugar factories, and after returning to his native Haarlem developed a profitable line in exotic landscapes populated by Brazilian animals.

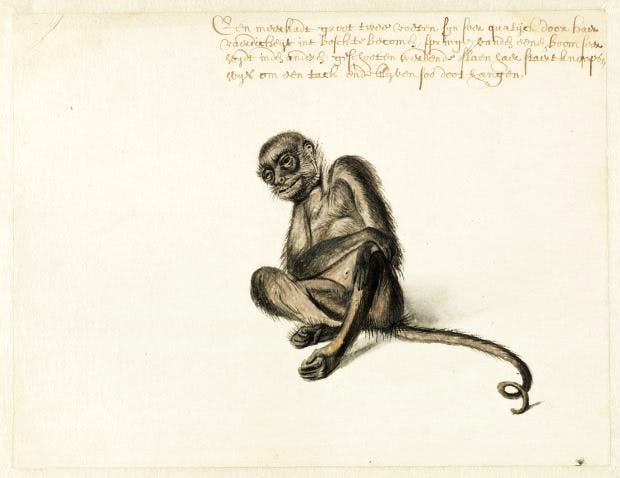

‘Spider Monkey, c.1638–1644, by Frans Post. Watercolour and gouache, with pen and black ink. Photo: Noord-Hollands Archief

The animals in these paintings were always assumed to have been based on specimens in Maurits’s private zoo, but no working drawings were thought to have survived. Then six years ago a sharp-eyed curator digitising the collections at the Noord-Hollands Archief in Haarlem came across a group of 34 gouache and ink studies of Brazilian animals and bingo! found they slotted neatly into Post’s landscapes in the selfsame poses. Joined in the exhibition by a taxidermic petting zoo of stuffed anteaters, armadillos, capybaras, sloths and porcupines on loan from the museum of natural history in Leiden — which, by a stroke of luck, is closed for renovation to make way for a newly acquired Tyrannosaurus rex — Post’s charming, slightly cartoonish animal drawings make for the ultimate family-friendly exhibition.

For Post himself, however, there was no happy ending. Some time after the jolly portrait painted by his friend Frans Hals in the 1660s, his fortunes deteriorated. Gradually the exotic animals vacated his pictures and in 1679, when Maurits decided to make a gift of his Brazilian views to Louis XIV and thought it would be a nice idea if the artist went along to provide a commentary, he was tactfully informed by his agent that Post had ‘fallen unnoticed into drunkenness’ and would not make a commentator fit for a king as he was suffering from the shakes. A year later, he was dead.

‘The beach at Scheveningen’, 1658, by Adriaen van de Velde. Photo: Gemäldegalerie

Adriaen van de Velde (1636–72), whose exhibition has just come to Dulwich Picture Gallery from the Rijksmuseum, fared slightly better. Although less famous than his marine painter father and brother, both called Willem, he was relatively successful during his short life and not forgotten after his death: in the 18th century his works were more sought after than Rembrandt’s. The breezy beach scenes and bucolic visions of Dutch Arcadias in this, his first-ever monographic exhibition, demonstrate why. His beautifully painted cows, sheep, goats and horses make Post’s animals look as primitive as they are exotic, and his ravishing red chalk figure drawings anticipate Watteau’s. His versatility may have been his undoing in a market that preferred to pigeonhole artists. There’s no evidence that he took to the bottle, but his wife had to open a linen shop to make ends meet and when he died at the age of just 35, he left her with debts.

It seems a pity Van Hoogstraten didn’t publish his advice to artists sooner, though it might not have helped. When the ‘supposed art connoisseurs’ are the ones with the money, what can you do?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in