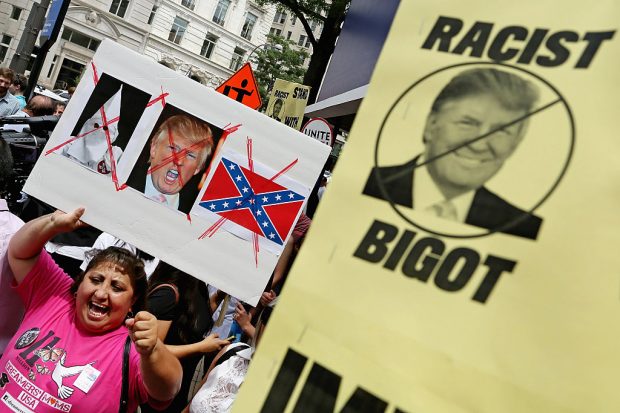

Talk of Donald Trump really draws a crowd.

Talk of Donald Trump really draws a crowd.

For example, few people would have known of Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein, the United Nations human rights chief, before he made a series of public statements on Trump over the past two months.

Hussein levelled criticism at conservative leaders across the world for their political extremism. In particular, he targeted Trump, warning of discrimination and torture under his presidency. The world’s media took notice.

Some news outlets embraced Hussein’s candid remarks, publishing them in full. Others said it was inappropriate for a UN leader to interfere in any national political process. Still others found irony in the fact that the comments on human rights came from a prince of a country with a chequered human rights record, the Kingdom of Jordan.

Hussein suddenly became newsworthy. But the result for human rights was mixed.

Sure, Hussein drew attention to the reality that nationalism undermines human rights. But he also seemed to cast a vote. He showed a preference, by default, for Hillary Clinton. For, if not Trump, then who else? More specifically, he showed a preference for Clinton despite the credentials of her party.

The UN human rights chief voiced fears that under Trump, terrorist suspects would be tortured. However, there is a public history of torture under the Democrats – Barack Obama has freely admitted his administration “tortured some folks”.

The choice between Clinton and Trump may merely be a choice between a president in favour of torture and a president in favour of somewhat more torture.

It is likely that whoever wins the presidential race; Guantanamo Bay will still hold prisoners without trial. The US-led wars will continue. Some of the lowest rates of pay in the Western world, provided by US employers, will persist. Poverty will remain, particularly among African Americans. The death penalty will continue. The list of adverse repercussions for human rights goes on regardless of which nominee is elected.

But Hussein recognised only the most flagrant threats by Trump. In doing so, the UN human rights chief unwittingly watered down the UN’s human rights standards. He communicated to the world that the international human rights regime is no longer the champion of an ideal concept of justice. It simply takes a pragmatic line of least resistance.

Of course, Hussein is not alone. There is a noticeable trend of UN officials and human rights NGOs taking sides on national elections and referenda – often the moderate side. Even the softly spoken, outgoing leader of the UN, Ban Ki-Moon, has raised questions about Trump’s stated policies.

There are other examples of apparent pragmatism by human rights groups. Last year’s referendum on economic reform in Greece saw UN Special Rapporteurs support the position of the Syriza party, seemingly considering the party the lesser of two evils. Yet Syriza’s promises to stand up to the demands for Greek economic austerity were illusory. Despite the referendum result, the party promptly gave into European economic pressure, leaving Greeks no better off on the human rights front.

Then during this year’s UK referendum on Brexit, the prominent human rights NGO Front Line Defenders also took a political position. It painted Brexit as “poison” for human rights. Yet the European Union, which the NGO defended, is hardly known for its progressive economic policies. Even its Court of Justice, which can hear human rights complaints, has famously restricted rights of unions and of imported workers.

So much for liberté, égalité, fraternité. Human rights might as well stand for médiocrité.

Taking sides in a political contest, where there are bound to be poor human rights outcomes whichever side wins, compromises human rights advocates. These advocates effectively show they are willing to tolerate contraventions of human rights in seeking “least worst” outcomes.

Advocates would be better off focusing not on politics, but on concrete human rights issues: on jobs, on living conditions, on the plight of disadvantaged people in society, on any of the wide range of issues confronting the world. They should make demands, not concessions.

When Hussein fills in his human rights report card on the Republican candidate, he should do so for the Democratic candidate, too. He may also wish to comment on the limits of democracy in the US, where Trump and Clinton are virtually the only candidates on offer.

Maybe this approach will not afford him as much media attention. But at least Hussein will preserve the credibility and raison d’être of the human rights enterprise. Otherwise, human rights may fast become the social justice mechanism of yesteryear.

Dorothea Anthony is a sessional lecturer and PhD candidate at the Faculty of Law, UNSW Australia

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in