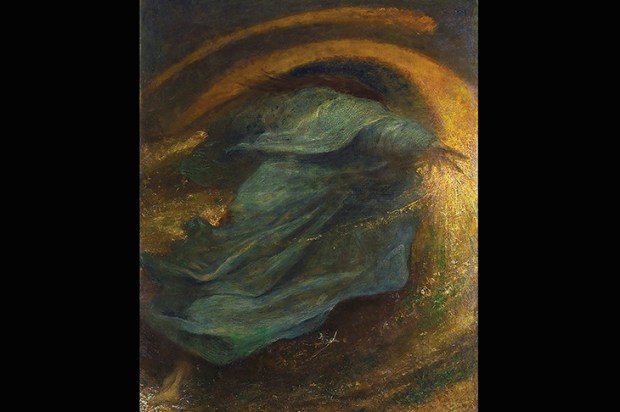

We don’t know what Caravaggio himself would have made of Beyond Caravaggio, the new exhibition at the National Gallery which is devoted to his own work and that of his numerous followers. But, by chance, we do have a very good idea what he would have said at least of one exhibit: ‘The Ecstasy of St Francis’ (1601) by Giovanni Baglione. Two years after this was painted, in 1603, Caravaggio stated in a disposition to a Roman court that he didn’t know of any other artist ‘who thinks Giovanni Baglione is a good painter’.

Very few of Caravaggio’s own words survive, and those that do are mainly in the records of legal cases in which he was involved. But these are enough to give an idea of his demeanour. As Baglione himself wrote later — when the great man was safely dead — Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610) was ‘a satirical and proud man’. He would, Baglione complained, ‘speak badly of the painters of the past, and also of the present, no matter how distinguished they were, because he thought that he alone had surpassed all the other artists in his profession’. But then, Caravaggio had every reason to be arrogant. He was — as the National Gallery exhibition demonstrates — very, very good. This, paradoxically, is its main problem.

The subject is not so much the painter himself, but his influence and his followers, the Caravaggisti. There were an awful lot of these, as Baglione complained, ‘many young artists followed his example’. With extraordinary speed, given the pace of 17th-century communications, word of his sensationally naturalistic way of painting had reached as far as the Netherlands when Caravaggio himself was barely 30.

This was more or less at the moment he was producing the National Gallery’s own ‘Supper at Emmaus’ (1601) and ‘The Taking of Christ’ (1602) from Dublin. Seeing these side by side amply explains why he made such an impact. The naturalism of, say, the left-hand disciple in the ‘Supper at Emmaus’ — starting with surprise and half rising from his chair — is still amazing, four centuries later.

A closer look provides some clues as to how Caravaggio achieved this: by painting exactly what was in front of him. This meant posing the figures one by one. The disciple on the left and the one with his arms flung out on the right look very much as if modelled by the same man. The latter disciple is definitely the same fellow as the two armoured soldiers in ‘The Taking of Christ’ because — as David Hockney points out in the new book we have written together, A History of Pictures — all of these men have an identical growth on their noses. Caravaggio was depicting what he saw, literally warts and all.

The Caravaggio effect — hyperrealism of texture and detail, plus the deep darkness and the spotlit illumination which Hockney has called ‘Hollywood lighting’ — was copied throughout Italy, France, the Netherlands and — though the exhibition doesn’t get quite that far — in Spain by the young Velázquez.

This is an exhibition of the same currently fashionable type as Rubens and His Legacy last year at the RA, and Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art this spring at the National Gallery. The pitfall, potentially, with all such exercises is that the grand original may upstage all the imitators. This did not happen with Delacroix, partly because his artistic progeny — Van Gogh among them — were so varied and so strong. It does with Beyond Caravaggio, though.

There aren’t very many pictures by the man himself on display, partly perhaps because the selection is largely drawn from collections in Britain and Ireland (after London, it goes to Dublin and Edinburgh). The curators have compensated by dotting the few they do have through the exhibition. Unfortunately, however, when there is a Caravaggio in the room it tends to blast everything else off the walls.

This is unfair, as a number of Caravaggio’s artistic progeny were highly distinguished. At least two of them, Jusepe de Ribera and Georges de la Tour, were great painters in their own right. Ribera is represented by three pictures, one of which — ‘Saint Onuphrius’ (1635), a study in the flabby, wrinkled softness of elderly flesh — does hold its own against the Caravaggio that hangs beside it. De la Tour does less well, mainly because the example in the show, ‘Dice Players’ (1650–51) is well under his best (and may be partly by his son).

There are nice things to discover throughout: Adam de Coster’s ‘A Man Singing by Candlelight’ (1625–35) is a charming Baroque nocturne, for example. Overall, however, the impression is of too many artists trying to do the same thing — and one supreme master of brilliant lighting and inky shade overshadowing all the rest.

The post Overshadowing all the rest appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in