It’s the Brits wot won it. That is, the US presidential election was won for Donald Trump with the help of a bunch of British nerds — data scientists from a company called Cambridge Analytica. This was the claim, at least, made by the company in a press release a couple of days after the election. ‘No one saw it coming. The public polls, the experts, and the pundits: just about every-body got it wrong. They were wrong-footed because they didn’t understand who was going to turn out and vote. Except for Cambridge Analytica…’ Frank Luntz, a famous pollster and one of those so embarrassingly mistaken, said: ‘They figured out how to win. There are no longer any experts except Cambridge Analytica.’

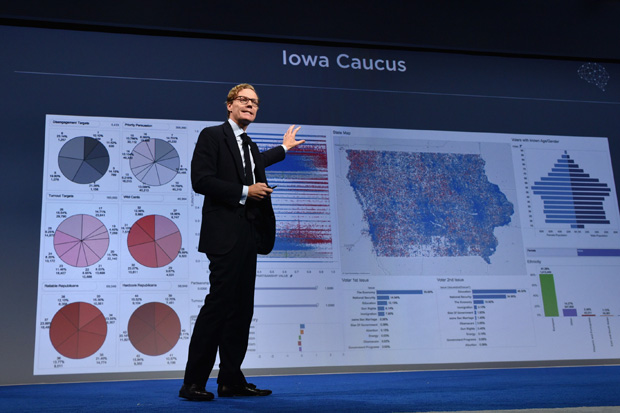

Trump, it turns out, was not just a billionaire with a big mouth and a Twitter account. The ‘authentic’ candidate, the roaring id who supposedly disdained traditional campaign pollsters and consultants, had quietly hired this British company in June and paid them millions. Cambridge Analytica — named after the university: branding to appeal to US customers — say they bet on Trump when no one else would. The chief executive, Alexander Nix (Eton; Manchester), told me: ‘The American political market is the most competitive and hostile in the world. A lot of vendors refused to work for Trump because they didn’t believe he had a cat’s chance in hell of winning. Cambridge Analytica did the opposite. We invested in Trump.’

Cambridge Analytica began the long election cycle working for Ted Cruz and then, after he failed, moved to Trump. There are reports that their main investor is the secretive hedge-fund billionaire Robert Mercer — and that this switch from Cruz to Trump tracked his allegiances. The company won’t comment on who their investors might be. They say it wasn’t connections that saw off the American competition but their unique approach. This, controversially, includes making psychological profiles of the electorate. They group people with similar traits and design political advertising to match: this is ‘psychographics’. The company has on file more than a million personality tests completed by Americans — online, by phone, or because someone with a clipboard approached them while they were shopping. You rate yourself against 120 statements — I dislike myself; I’m the life of the party; I make rash decisions — and are graded on what psychologists call the ‘big five’ personality traits: openness, conscientiousness, agree-ableness, extroversion, neuroticism.

‘The impressive bit,’ says Nix, is to expand the findings from those who took the personality tests to the entire American electorate of 230 million. They can do this because Cambridge Analytica also has ‘4,000–5,000 data points’ — pieces of information — on every single adult in the US. This can be anything from age, gender and ethnicity to what magazines they buy, which TV programmes they watch, the food they eat, the cars they drive, even the golf clubs they belong to. This is indeed impressive — and a little bit creepy. Regardless, the data is for sale; Cambridge Analytica take it and (they have persuaded their clients) spin it into gold. There are two assumptions: first that people who buy the same things and have the same habits — the same ‘data points’ — have similar personalities; secondly that your personality will help predict, say, whether you go for Coke or Pepsi, Clinton or Trump. ‘Behaviour is driven by personality,’ Nix said.

To the detractors, this is pure fantasy. One Republican political consultant said: ‘Their thesis is people don’t know what they think about politics but we can anticipate what they will think based on their personality types. That’s nonsense.’ Political consulting — the business he was in — was full of characters like the Duke and the King in Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, schnorring the yokels and relieving them of their wallets. ‘It makes perfect sense that Donald Trump used these people. You’re talking about a guy who lost money on red meat and professional football, booze, sex, gambling, discount airfares and higher education in the United States. He went broke doing things it’s impossible to lose money on in this society, so he’s very good at being played for a rube.’

A Republican data scientist for a rival firm said he did not use psychographics. ‘If you get a voter on the phone, why are you asking them what their favourite ice cream is or what their favourite colour is — why don’t you just ask them who they’re going to vote for?’ He added: ‘They’ve got a smooth-talking Brit wearing Savile Row suits who gives you a great pitch and wows you a little bit; they’ve got a great PR operation, but with psychographic profiling, there’s nothing there. They’re really, really smart people. It’s like they’re a bunch of board-certified doctors who decided to make a lot more money selling snake oil.’

That charge is wearily familiar to Matt Oczkowski. At 29 he is a veteran of eight years of political campaigns and he ran Cambridge Analytica’s Trump data operation. ‘The snake-oil salesman stuff is probably just someone who never believed in the methodology to begin with. This is much more a case of jealousy than it is legitimate and scientific argument. Most Republican political consultants have no conception of what a data programme is.’ He was tired of having to defend the company. ‘Given the results of the election, I feel like other people will have to start defending themselves to us.’

Actually, there was very little psychographics in what he did for Trump. There wasn’t time: they’d had to set up the entire data operation ‘from scratch’. Instead, they did a huge amount of more conventional polling and psychographics was used — he maintains — to get better predictions out of it, updating ‘methodologies that have been used the same way since the 1970s’. They simply had a better picture of what the electorate looked like, Oczkowski said.

The problem, says Jill Lepore, a historian of polling at Harvard, is that while traditional polling was bad for democracy and could be unreliable, data science was still more damaging. Politicians’ views were dictated by consultants, not principle, while voters were told only what they wanted to hear. ‘The effects of data science on the political process are probably considerably worse. Data science is the solution to one problem but the amplification of a much bigger one — the political problem.’

She was talking about the key to it all: ‘microtargeting’. Cambridge Analytica sliced and diced the electorate so Trump could talk to small groups directly, or even one at a time: one email or letter to the timid introvert at No. 22 who cares about jobs and limited government, another to the loud extrovert next door who cares about gun rights and Isis. Psychographics was used in what Oczkowski calls ‘sentiment analysis’ and ‘tonality’, that is in deciding what to say to people and how to say it. Almost 50 years after The Selling of the President was written about the advertising industry’s intrusion into politics, this is the ultimate attempt to manipulate the electorate.

Nix, Cambridge Analytica’s chief executive, is evangelical about this. ‘What we’re seeing is not about politics. Communication is fundamentally changing. Creative-led blanket advertising is being replaced by data-driven individualised advertising. This can only be good. The advertisers get a much better return on investment; the consumers are not being bombarded with adverts for things they don’t care about.’ Don Draper is dead — replaced by a twentysomething chugging Diet Coke at a laptop.

The clients seem to like it. Trump reportedly spent only a third as much as Clinton on TV advertising. ‘Cambridge Analytica bullshit a lot,’ said a senior figure in the campaign here for Brexit, echoing the American consultants, but ‘if you are a smart client you can definitely get value out of them’. Trump had already announced his rust-belt strategy before Cambridge came on board. But Oczkowski says he ‘greatly influenced’ where the candidate travelled, based on the ‘density of persuadable voters’. ‘We certainly don’t take credit for any strategy,’ he was careful to say, but ‘we reinforced decisions that Mr Trump had already decided to take’.

You might think from a casual reading of the Cambridge Analytica press release that they predicted the outcome of the election. They did not. A company spokesman called reporters before election day to say that Trump had only a 20 per cent chance of winning. That was increased — in an internal assessment — to 30 per cent as people went to vote. Having put the entire nation on the couch, Cambridge Analytica got it just slightly less wrong than all the conventional pollsters. ‘We saw it coming in terms of the trends,’ Oczkowski said, ‘but in terms of actually predicting a win, we knew it was a possibility but we couldn’t say definitively that it was going to happen.’

This is comforting. The human heart remains unknowable. Elections remain fickle things. And despite data science, the warning to journalists from this astonishing presidential election still stands. Never again should we begin a report: ‘According to opinion polls…’

The post The Brits behind Trump appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in