On the London Underground last week the carriage was crowded. No seat. No problem. I’m only 67 and content to stand. But a younger man offered his seat, and, having some way to travel and a book to read, I accepted with the appropriate grunt and nod of gratitude. Later, approaching my station, I noticed he was still there. Should I thank him properly before alighting? But he was in another part of the carriage. It might look silly to elbow my way over. Let it pass.

Then a voice in my head spoke, a voice that over the decades has become so familiar. Don’t misunderstand me: this was not my conscience. My conscience was clear. It was definitely not necessary to thank this chap again. So the voice was not chiding but simply stating a fact: more like a weather forecast than an admonition. ‘I know you,’ it said. ‘I know what you’re like. If you fail to thank him, then after you’ve left the carriage, you will feel you really should have. You don’t feel that now, but you will, and it will discomfit you.’

Recognising the accuracy of this forecast, I did walk over and thank him. I still saw no need, but wished to save myself feeling bad about it later. As soon as I’d done this I felt content, just as the voice had predicted.

Many years ago, when middle-aged, I was in a little town called Urcos, near Cuzco in Peru. I was writing a book about Andean travels and had left my companions in Cuzco, whence we were all booked to fly into the Amazon to a riverport called Puerto Maldonado. But it was also (some said) possible to get there by road, and Urcos was where lorries began the rough road over the mountains and down into the rainforest. So I’d told my friends that if I didn’t return, it would be because I’d found surface transport; in which case I’d see them later, down in the jungle.

But only two lorries were going, one was full and the other (loaded with 64 loose and leaking 44-gallon oil drums) was crowded with poor and frankly smelly South American Indians. The driver said it would take three days and we might get stuck, and if I wanted to come I’d better jump on now — without provisions — as he was about to leave. I resolved not to face the privation or take the risk: there was already plenty of good material for my book.

Then came that old, familiar voice. It made no recommendation, it offered no exhortation: it simply advised that if I didn’t go then this would cause me regret before the lorry had even passed from sight. So I jumped on. That journey, and the peasants, prostitutes and chancers who became my comrades, formed the centrepiece and best chapters of Inca-Kola, still in print today.

At the risk of labouring the point, let me again emphasise that the voice is not judgmental or exhortatory: it simply forecasts. The voice can forecast because the voice and I are such old friends. Having learned through experience how accurate its insights prove, one would ignore it (as sometimes happens) knowing one was sure to regret the decision.

As we grow older we deteriorate in many ways, and faster than we like to admit. All our physical capacities decline, mostly from a young age. More of our mental capacity deteriorates, and faster, than we care to acknowledge. Comforting ourselves, we oldies love to reflect that qualities like ‘maturity’ and ‘judgment’ are showered liberally upon us by the passing years, even as muscle and mental arithmetic fade. We bandy words like ‘wisdom’.

Of this compensatory increase in sagacity, I’m sceptical. Most wars have been started by old men, and some of the silliest judgments in history have been made in brains that have lost the suppleness, and minds that have lost the openness, of youth. To the ‘wisdom of the years’ theory, one must respond with an ‘up to a point, Lord Copper’.

But my own experience, surely not untypical or I wouldn’t bother you with it, is that there’s one blessing that does steal upon us with the years. We make and cultivate and deepen the most important acquaintance of our lives: the acquaintance with ourselves. We know ourselves better and better, and it’s tremendously useful.

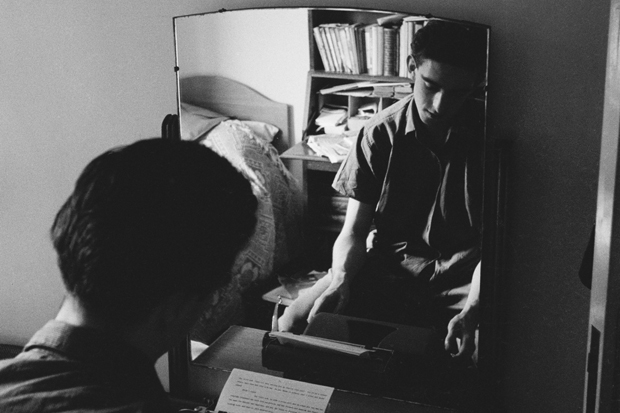

At first we’re strangers. I do not know when the child first meets himself or herself. It’s perhaps gradual, though it’s likely the encounter begins quite early, perhaps at two or three. But there must be a point after which not only is the toddler looking out of the mirror recognised by (and as) the one who’s looking in, but the mind and personality of this (at first) stranger is acknowledged as the companion who is to shadow us until death. He or she is our self, but the union is never complete, the two never fold together into one, the one remains always able to inspect the other from the outside, and our whole life is to be a deepening of the relationship.

‘Silly old Matthew,’ I say to myself, with both affection and mockery, as I contemplate what I’ve just said or done, or thought or planned. This person-to-person remark is not just a figure of speech: I really do feel there’s an individual there before me, whom I may admire, pity, disapprove, but increasingly understand.

How well I know him now. It has taken a long time, this comradeship of some 65 years, for us to click properly. We used to surprise (even shock) each other. When ITV telephoned to ask if I’d like to quit the House of Commons for a media career, I heard the alter-ego say ‘Yes!’ before I’d even realised he had despaired of a political career. But with age we’ve settled into a wonderful rapport, offering me the best companion and adviser a man could have: the old friend who has long passed being approved or disapproved of, but who’s just there.

Silly old thing. I know him so well.

The post The one thing that really gets better with age appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in