Given that he wrote and published some of the most stunningly handsome books of the 17th century, John Ogilby has not been served well by literary history. The Fables of Aesop (1651), the first complete English translation of Virgil (1654), a two-volume edition of the Authorised Version of the Bible (1660) plus vernacular versions of the Iliad (1660) and Odyssey (1665) were all magisterial folios, produced with the clearest of type, the widest of margins and on the heaviest of paper. Ogilby wrote specifically for those with deep pockets and fine libraries, an elite book-buying public who could afford translations illustrated with copious and expensive engravings. He would have been particularly nettled, then, by John Dryden’s influential assessment of his legacy in the verse satire ‘Mac Flecknoe’ (1676), written in the year of Ogilby’s death. Listing him among a handful of ‘neglected authors’, Dryden described Ogilby’s works as ‘Martyrs of pies, and relics of the bum’.

It is extremely unlikely that anyone would have wiped their backside or lined a cake tin with an expensive page of Ogilby. Indeed, when Dryden himself recycled Ogilby he only did so to enhance the appeal of his own poetry, reprinting 101 of Ogilby’s engravings to accompany his magnificent new translation of The Works of Virgil in 1697. Dryden’s hostile swipe, then, was actually designed to define the critical response to an eminent rather than a ‘neglected’ author, someone he rightly regarded as his inferior (as both poet and Latinist) but who had somehow managed to position himself at the very centre of Restoration culture.

Alan Ereira’s book tells the fascinating story of Ogilby’s journey to that centre. Ogilby ended his life having been, variously, a tailor, a dancing master, a soldier, a theatre manager and impresario (he established the first Restoration theatre in Dublin), a translator, a poet, a publisher, a pioneer of subscription publication and the man who devised the civic pageantry for Charles II’s coronation. While fulfilling these roles, he got to known many of the great and good of 17th-century England. Having come from obscure origins just outside Dundee, he was employed in the household of Thomas

Wentworth, the Earl of Strafford, benefited from the patronage of James Butler, the Duke of Ormonde, and through his friendship with the biographer John Aubrey got to know those leading members of the Royal Society, Robert Hooke and Christopher Wren (though he was never a member himself).

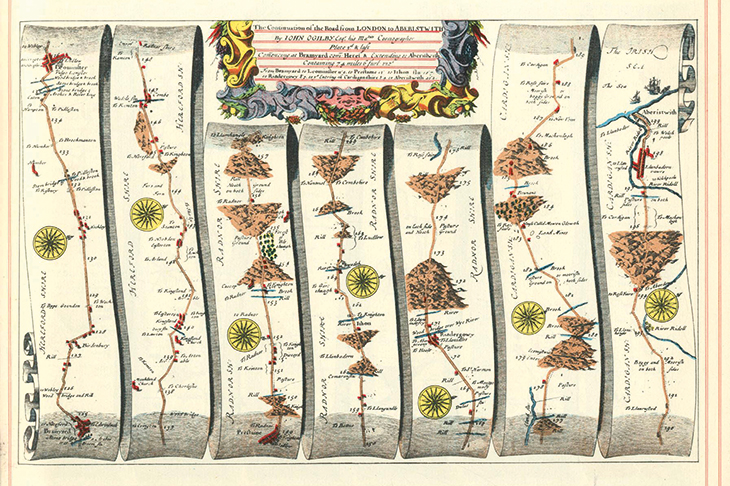

During this later period he was appointed Charles II’s ‘Cosmographer and Geographic printer’, and orchestrated an ambitious project to map the roads of England and Wales for the king. MArcusThis culminated in yet another beautiful, lavish book called Britannia, Volume I (1675) which, by charting entire road routes rather than tracing counties and their boundaries, was effectively Britain’s first road atlas.

The thread uniting this rich and diverse life, quantified as ‘nine lives’ in Ereira’s title, was devotion to absolute monarchy in general and the Stuart dynasty in particular. Ereira is completely right to see each of Ogilby’s projects as reasserting the prestige of the royal cause in tumultuous times. His Virgil translation, for example, offered consolation to those exiled servants of monarchy during the Cromwellian Protectorate — like Aeneas fleeing the destruction of Troy, they endured epic struggle, a descent into hell, but would ultimately emerge victorious.

As high-status luxury objects, the materiality of Ogilby’s books was designed to console that audience, too: exclusivity and courtly refinement weighed heavily. In the case of Britannia, the heft was both literal and figurative. With 100 copper-engraved maps and 200 pages of chorographical description, the book came in at almost 8kg and cost £5 to buy — nudging £700 in modern money. It was thus self-consciously placed beyond the reach of ‘the vulgar’.

Charles II himself took special pains to ensure that subscriptions to Britannia remained buoyant. This wasn’t because the book was brilliantly useful as a navigational aid (it was far too heavy to be consulted on a journey; it was too expensive to cut maps from and it contained no information about the growing urban centres of Bradford and Sheffield, nor the strategically significant port of Liverpool). Rather, the book was important to the king and his advisers because it projected an image of an absolutist monarch with a panoptic gaze: one who has measured, plotted and surveyed all routes through his territories. If James I had his apotheosis in the Rubens ceiling at the Banqueting House in Whitehall, then Charles II found his in Ogilby’s Britannia, as Ereira acutely observes.

Narrating the sheer variety of Ogilby’s life and output is an enthralling way of reading about the connections between culture and monarchical power in the 17th century. Ereira has an expert grasp of all primary biographical material and has done the heavy lifting in the archives (for instance, he expertly rereads one of Elias Ashmole’s ciphered horoscopes to show that Ogilby broke his leg at 18 and not at eight, as previously assumed).

It’s a shame, therefore, that he has decided to ‘sex up’ the Ogilby dossier, by giving it the narrative arc of a thriller, when the material is completely thrilling on its own. He continually asserts that Ogilby moved through the various stages of his life by hiding something, concealing family connections or occluding political statements, as if he were a 17th-century Dan Brown hero on the run from Dark Forces, disguised as an undefined bunch of Puritans and moderate Parliamentarians. Ogilby is repeatedly referred to as a ‘secret man’, an ‘undercover aristocrat’ with a ‘hidden life’, forever ‘hiding its secrets’; Britannia was a ‘handbook for conspiracy’.

Such hyperbole perhaps says more about the frustratingly stubborn archival silences engulfing the lives of non-aristocratic individuals who sought advancement at the Stuart court than it does about the subject of this informative and entertaining book.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in