Michael Andrews once noted the title of an American song on a scrap of paper: ‘Up is a Nice Place to Be.’ Then he added a comment of his own: ‘The best.’ This jotting was characteristic in more than one way. A splendid exhibition at the Gagosian Gallery, Grosvenor Hill, London, makes it clear that Andrews was — among other achievements — a supreme aerial painter. No one else has better caught the sensation of floating, to quote another song from the Sixties, up, up and away.

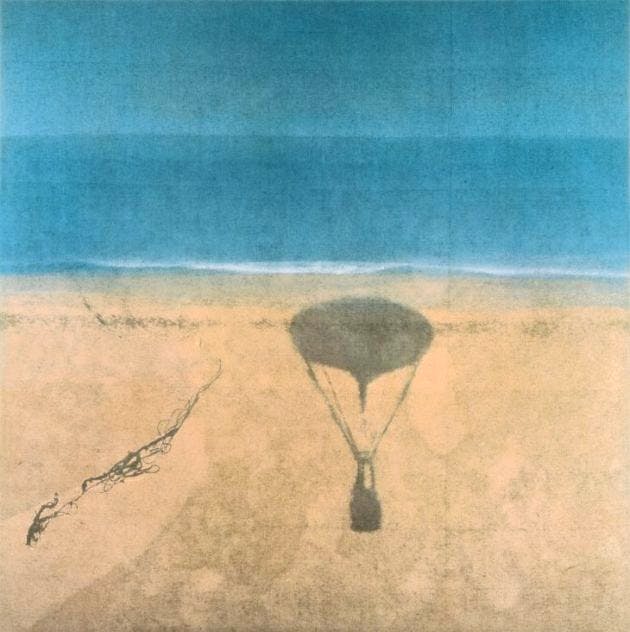

It was also typical of Andrews that his addition to that title was only two words — but it makes a big difference. His paintings are like that. At first, there may seem not to be much there. ‘Lights VII: A Shadow’ (1974) is almost a painting of nothing at all. Its subject is the silhouette of a balloon, seen from above, drifting over the sand of an empty beach, with bands of blue sea and sky beyond.

‘Lights VII: A Shadow’ (1974) by Michael Andrews

The effect is quite close to an abstraction. But for the spot-on verisimilitude of that shadow — with ropes and dangling basket clearly outlined — you might be looking at a Rothko. On the other hand, a glance at a reproduction could suggest that this is a photograph. Indeed, as the curator Richard Calvocoressi explains in the catalogue, the sources for Andrews’s later works were often photographic. As part of his research for the picture, Andrews assembled shots of coastal scenery and images of inflated balloons in flight. The changes he made to his sources might seem a matter of nuance, but they were crucial.

When you stand in front of the finished work, you understand how subtly these raw materials have been transformed into paint. The texture of the beach, sprayed on, is dry and granular with the raw canvas showing through, except for one detail — a tangled skein of pigment, thick and viscous, which looks as if it has been flung at the surface in the manner of Jackson Pollock, or Andrews’s friend and mentor Francis Bacon. What this represents is not obvious — seaweed? Flotsam? — but it perfectly punctuates and animates the picture.

As both man and artist, Andrews was hard to pin down.

Initially, Andrews’s work seems ‘mysteriously conventional’ (a phrase he liked). It was famously quipped that he was ‘in danger of being taken for a rumour rather than a person’. He worked very slowly: this medium-sized exhibition contains most of the important paintings from his last three decades. His friend — and enthusiastic advocate — Frank Auerbach has compared Andrews to Vermeer in that both, despite a small output, ‘left a great impression’ because each picture ‘contains so much information, both sensory and aesthetic’. But that output is also uneven, as is inevitable when an artist is constantly trying new things. ‘A Shadow’ is fabulous; its successor, ‘A Cabin’ (1975), representing a plane swooping over a city, doesn’t quite come off. The drawing of the aircraft is uncharacteristically clunky.

Brought up a Methodist in Norfolk, Andrews (1928–95) spent his early adulthood in London’s artistic Bohemia. Its headquarters in the 1950s and early ’60s, The Colony Room, a celebrated Soho watering-hole, was the subject of a painting from 1962. It incorporates portraits of Andrews’s friends Bruce Bernard and Lucian Freud, plus the back of Bacon’s head. His early works, of which there are only a few in this exhibition, were often about people and parties. But in his later decades Andrews was almost exclusively a landscape painter, hence the title of the Gagosian show: Earth Air Water.

He painted Scottish moors, where amazingly enough he loved to go deerstalking, and Ayers Rock in the Australian outback. Another series from the 1970s, dealing with the improbable subject of tropical fish, reveals Andrews as master of evoking the sensation of swimming, merging into a watery world of translucent reflections.

Andrews had a knack of eluding stylistic categories. Initially, he studied at the Slade, following the reticent, objective approach of William Coldstream, leader of the Euston Road School. Simultaneously, he learned from Bacon that paint can be handled in ways wild and free. But even so in Andrews’s case you are seldom conscious of the hand of the artist, wielding the brush.

‘Thames Painting: The Estuary’ (1994 – 1995) by Michael Andrews

Indeed, increasingly he did not use a brush at all, preferring to blow pigment on to his pictures. In his last completed work, ‘Thames Painting: The Estuary’ (1994–5), he employed a hairdryer to drive it across the surface, producing a perfect parallel to the runnels and washes of low tide. The grasses in the foregrounds of his 1980s pictures of Ayers Rock were created by holding real spinifex grass, sent from Australia, against the canvas as a stencil.

Andrews learned something else from Bacon: that contrary to modernist dogma, paintings can tackle the great enigmas of existence. Bacon read Aeschylus, and his works — like Greek tragedy — are concerned with violence, sex and death. In contrast, Andrews’s preoccupations were those of the beat generation: spiritual enlightenment, Zen and the Art of Motor Cycle Maintenance, being and nothingness.

His later pictures are often metaphors, but not in a crude way. ‘The ideas dissolve,’ he once said, ‘reassemble and come up as a completed picture.’ The balloon, for example, struck him as a ‘perfect image’ for a phrase that he came across in a book about Zen Buddhism: the ‘separate ego enclosed in a bag of skin’. But you don’t need to know that when you look at the paintings. You feel the meaning. In the same way, it’s not hard to intuit that ‘The Estuary’, painted when Andrews was dying, is about departure: the Thames as River Styx.

Since his relatively early death, Andrews’s reputation has remained floating and elusive. A Tate retrospective in 2001 failed to propel him to the international artistic stratosphere occupied by Freud and Bacon. But in the intervening years even some of the pictures that looked eccentric or weak 16 years ago — the fish, for example — have quietly metamorphosed into masterpieces. That’s a sign of greatness in a painter.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in