Kids: who’d have them? Certainly no one who has ever been to the opera. If they’re not murdering you, they’re betraying you, defying orders or throwing themselves into the arms of the nearest unsuitable suitor. What happens when that suitor is a god, or — god forbid — their own brother or sister? Answers came on the back of two very different operatic postcards this week.

At the Barbican, bathtime gone bad. A claw-foot bath sits centre stage, a cold, white womb in which monstrous twins writhe in fleshy ecstasy. Backs arched, legs flexed into Priapic verticals, they coalesce the clenching pulse of orgasm and the surging agony of childbirth into a single, exquisitely choreographed moment.

Combine choreographer-provocateur Javier De Frutos with Les Enfants Terribles — Jean Cocteau’s curdled fairy tale of an orphaned brother and sister whose mutual love is contorted into something inadmissible — and things were always going to get uncomfortable. What was harder to predict was the restraint and beauty of that discomfort.

Taking Cocteau’s novel and Jean-Pierre Melville’s film adaptation as a jumping-off point, Philip Glass’s 1996 ‘dance-opera’ is a theatrical hybrid, whose greedy quest after sensation heaps dance, song and spoken word together into a fantasy that outstrips its originals.

Glass distils the story down to just a central quartet of characters: siblings Paul and Lise, and Gérard and Agathe, the two outsiders drawn into their world of imagination. Originally each was doubled by both a singer and dancer. Here the characters are atomised still further, with four dancers each joining soprano Jennifer Davis and baritone Gyula Nagy (both Jette Parker Young Artists at the Royal Opera) in the central roles. The effect is bewildering, a sort of subjunctive reality in which what is and what might have been co-exist in real time. It’s a technique that mirrors Glass’s time-bending musical process — the repeating phrases that gradually phase and morph into variations of themselves.

There’s a sly innocence to Glass’s instrumental writing (scored for three pianos, meticulously directed here by Timothy Burke), the luminous arpeggios and scales transforming the music of the child-beginner into something mysteriously adult. But the vocal lines add little. Deeply unsympathetic, their chattering functionality reduces singers to tuned percussion. Set against the expressive freedom of De Frutos’s choreography — drawing on the vocabulary of both classical and contemporary dance —the restrictions imposed on Davis and Nagy are cruelly emphasised. Only mezzo Emily Edmonds (Agathe) finds the depth and range of tone colour to match her dancer-double.

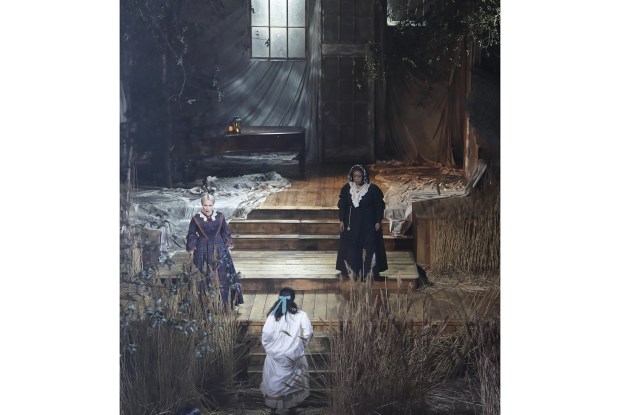

The thrills here are in the visuals: the intricate duet for Lise (Gemma Nixon) and Paul (Edward Watson) in which each, ‘like two halves of the same body’, fills the gaps left by the other; the alien strength of Zenaida Yanowsky’s Lise dominating Watson’s chameleon Paul; the exhilarating sense of motion achieved by Jean-Marc Puissant’s ever-shifting sets and Tal Rosner’s projections, now grotesque, now gloriously colourful against the chaste greys, creams and blush-pinks of the children. What could have been crudely erotic, obvious, instead remains a heady suggestion, suspended somewhere between innocent wish and obscene fulfilment.

But if the doings of Cocteau’s siblings shocked inter-war Paris, their impact was as nothing compared to Handel’s scandalous Semele. Semele is an opera disguised (with the aid of a few diaphanous choruses) as a modest oratorio fit for performance during Lent. But the composer was fooling no one, and his tale of a young woman who defies her father and rejects his chosen bridegroom in favour of a good time with Jupiter is Handel at his dramatic best.

It’s rare these days to hear a contemporary orchestra tackle this repertoire, but the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (directed from the harpsichord for this concert performance by period specialist Richard Egarr) just about made their case, give or take some uncomfortable tuning from strings denied the cushioned landing of vibrato. The soloists were more unanimous, with Mhairi Lawson’s Semele flirtatious through her coloratura showpieces, and Catherine Carby’s Ino/Juno warmly sung, if never fully dramatised. Stealing the spotlight from the supporting roles were Christopher Purves, who set the hall ringing as Semele’s imperious father Cadmus, Rowan Pierce’s charming Iris and countertenor Tim Mead, radiant as spurned lover Athamas.

The CBSO Chorus — the raison d’être, one suspects, of the unusual project — romped their way through Handel’s ensembles with energy, but the overall effect was still slightly unconvincing. With singers unsure whether or not to act within this concert setting, and performances neither strictly authentic nor gleefully anachronistic, this Semele felt less like an operatic wolf in oratorio’s woolly clothing than

the reverse.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in