Roy Hattersley would never have been born had it not been that his mother ran away with the parish priest who instructed her in the Catholic faith before her marriage to a collier — the priest conducted the wedding; a fortnight later they eloped. This deplorable episode had one happy consequence: the birth of Roy, who never knew the reason for his father’s ease with Latin until after he died.

So Roy is in a way a small part of his latest book, The Catholics, a history of the church and its people in Britain since the Reformation. He is an atheist but says, ‘Religion in general — belief in the

unbelievable — fascinates me.’ He’s well disposed towards his subject:

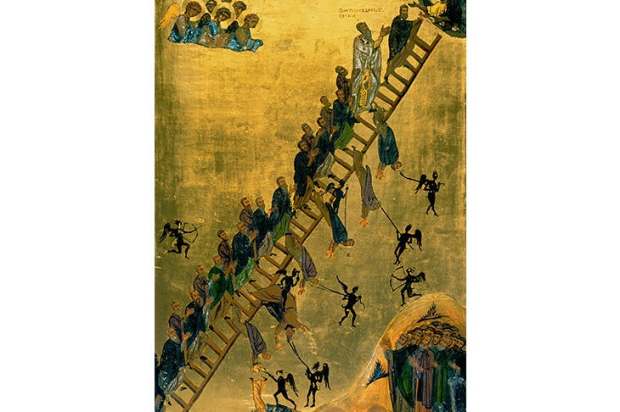

The history of the Catholic church… is an anthology of adventure stories…. Each one is a triumph of faith and a victory for the moral certainty that reasonable doubt cannot guarantee. Catholics survived the long years of persecution because…their faith allowed no compromise. Men and women do not willingly die in defence of common sense and sweet reason.

Which — a paragraph into the book —marks the first point at which I took issue with it: the belief in the unbelievable bit. If there’s one thing that Catholic tradition insists on, it’s on the compatibility of reason and faith; indeed, you could say it’s the starting point of Catholic theology. Ronald Knox, the celebrated convert priest, got so fed up with the ubiquitous Anglican assumption that Catholics swallowed their religion on the basis of authority that his book The Belief of Catholics includes a helpful list of things Catholics wouldn’t be invited to accept merely on the say-so of the Church: it starts with the existence of God.

The account that follows of the history of Catholicism is a spirited, if error-strewn trip through five centuries, sustained by Roy’s enjoyment of a good human story, and his underlying bafflement that religion really can be the cause of so much disagreeable behaviour. Whether it’s the Pilgrimage of Grace or the Gordon Riots, he surveys the appalling misconduct of religious people with civilised distaste and sympathetic incomprehension.

Some chapters are better than others, depending on his sources: that on Bloody Mary’s burnings owes a good deal to Eamon Duffy’s The Fires of Faith. But his account of the church at the Reformation seems not to have taken into consideration the latter’s groundbreaking and now established account, The Stripping of the Altars, which makes clear that the church in the early 16th century, so far from being irredeemably corrupt and clericalist, was in rude health and very thoroughly grounded in society from top to bottom. Indeed, it could and has been argued that the Lutheran Reformation, as adopted by Cranmer, was an interruption to the development of a reformation within the church, associated with humanism Much of his church history is out of date.

What Roy doesn’t take on board either — not even in his chapter on the Pilgrimage of Grace (‘naïve’) — is that lay involvement in parish bodies such as the guilds was a fundamental social bond. As for the effect of the dissolution of the monasteries on the poor, Roy gives it curiously little attention. He covers the ground briskly— five centuries in two kingdoms plus the Roman dimension — but this is a book by a plucky amateur, not an historian, and it shows.

He discusses the Scottish and Irish as well as the English church — they are very different beasts. He has his favourites:

unusually he prefers John Fisher to Thomas More; the author of Utopia gets short shrift. Cardinal Manning is another favourite, not least as a social reformer. He is, however, a little perplexed by the fame of Newman, but acknowledges that he, ‘though florid and convoluted… showed a respect for the language’, which is one way of putting it. He has firm literary views: he finds Greene and Waugh obsessed with sex and despair.

He views the condition of the church in modern times with affable sympathy, even if he is unfailingly fixated more by issues of contraception and divorce than by homosexuality. He’s relatively unmoved by the upheaval, as well as renewal, caused by the Second Vatican Council. He is baffled by the present resistance in parts of the church to Pope Francis’s willingness to allow for the admission to communion of divorced and remarried Catholics. Quite properly, he is indignant at the belated response of the authorities to the scandal of child abuse.

As for the collapse in the numbers of Catholics practising the faith, which is striking in the young, and even more pronounced in Ireland than in England, he hasn’t much to say. Still, given that there hasn’t been a comprehensive survey of the Catholic Church in England since John Bossy’s serious history in 1975, this is a brave, if flawed, attempt to fill the gap.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in