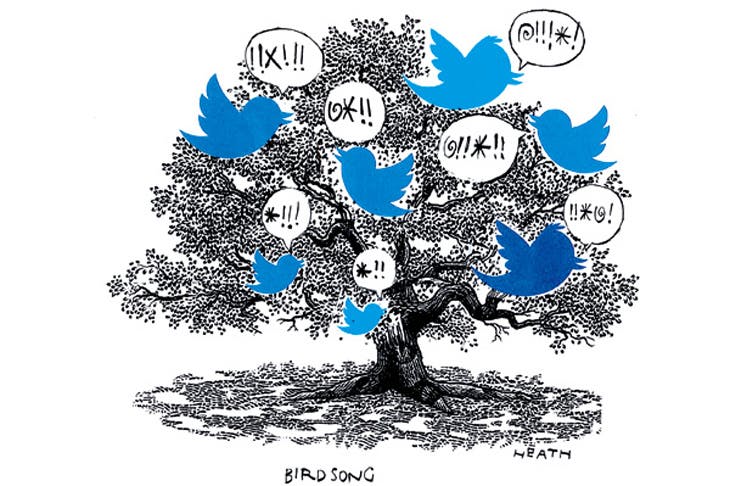

On Tuesday morning I was thinking to myself how oddly pleasant social media seemed. Then Theresa May dropped her election bomb. Immediately the posts started appearing: ‘Tory scum’ and ‘Tories launch coup’, then came the memes and I thought: I can’t take another two months of this. I’d only just tentatively returned to Twitter and Facebook following Brexit and Trump; now I find myself wanting to suspend my accounts again.

I think back nostalgically to general elections of yesteryear. I vaguely remember some fellow students being pleased about Blair winning in 1997 but most of us were more excited about seeing Teenage Fanclub at Leeds Metropolitan University. The polls of 2001 and 2005 passed by without me noticing. I think I voted Conservative but it may have been the Monster Raving Loony Party. It was difficult to tell the difference. From 1995 until 2007, I can count the number of political discussions I had on one hand.

In 2007 though, Facebook started to become ubiquitous. After a couple of months I realised that I was politically at odds with nearly every one of my friends. I had never realised quite how left-wing they all were. But it was only in retrospect that it was an important moment; at the time it didn’t matter that much. People were mainly there to post pictures of weddings, join silly groups, and poke each other (remember that?). I joined Twitter in 2009 and, being a freelance drinks writer, found it an invaluable way of making contacts, many of whom became friends. The politics was always there, but it wasn’t until 2010 when David Cameron became prime minister that it started to take on an edge.

Things went downhill fast with the Scottish referendum, the 2015 election, Corbynmania (that seems a long time ago) and then the orgy of self-pity that followed the EU referendum. That was the first time I suspended my accounts. Last November my initial thought when Trump was elected wasn’t ‘Russia is going to invade Poland!’ — it was ‘Oh no, Twitter is going to be a nightmare’.

It’s not that I’m apathetic about earth-shaking world events. I watch Trump with a kind of horrified fascination and for a time I read everything I could on Brexit. There are people on Twitter from across the political spectrum who are brilliant to follow because they have lots of interesting things to say. Most of us, however, don’t know what to say so we just express anger. One by one, friends I admire for their savoir-faire or whimsical takes on life have succumbed to ranty politics. I’ve seen clever people complain about ‘fake news’ one day and then the next post things approvingly from Corbyn propaganda website, The Canary.

The best example for how to trash a great reputation on Twitter, however, has to be the philosopher A.C. Grayling and his increasingly unhinged updates about the EU and Brexit. The quest for likes and retweets has encouraged every-one to get involved in politics, from Gary Lineker to the social media accounts of multinational companies. I am sure they are all convinced they are doing the right thing, fighting the good fight and convincing people, but in reality they are just preaching to the converted.

This sort of partisanship goes down well with the hardcore but it puts off everyone else. It can’t be a coincidence that as the political temperature goes up, Twitter itself is struggling financially. The number of tweets sent has declined from 661 million per day in 2014 to half that this time last year. Most accounts are dormant. The majority of tweets are sent by fewer and fewer accounts. It feels like it’s not the place for the open-minded, the centre-grounders or the apolitical. Twitter was once like a rowdy pub conversation, but lately the level of bile has made it more of a bar brawl. Jon Ronson’s book So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed is particularly enlightening on how much of the unpleasantness online comes from those convinced they are doing things for noble reasons. People say things to each other online that they would never say face to face. I have noticed, however, Twitter behaviour starting to percolate into real life. During one of my periodic social media breaks, a man I sometimes work with interrupted my lunch to hand me a printed-out article from the New York Review of Books about how Brexit would be a total disaster. Had he been carrying it around in case he ran into me, or did he just print copies out in case he saw people who disagreed with him on Brexit?

I wish I could say that I have remained above all this, but I have succumbed to the lure of the online rumble — once disastrously, while drunk, involving an old friend who I haven’t really spoken to since.

A break will, I hope, work wonders for my friendships, but it’s also amazing how much work you can get done when you’re not involved in multiple online spats. As the novelist Ned Beauman wrote recently: ‘I’m impressed with anyone who can follow all the skirmishing on here and still maintain the same level of creative output and general wellbeing. I prefer not to maintain a state of simmering irritation and disgust throughout every waking hour.’

My regret about giving up social media is that as a self-employed father working from home, it is often my only daily interaction outside my family. I have tried to find alternatives. I joined Instagram but my photos are terrible and everyone else’s carefully curated lifestyles make me feel a bit inadequate. Friends have suggested I use WhatsApp, but I think the answer might be to employ the telephone. I’m going to call friends and meet them in the pub or have them over to dinner. There’s nothing like seeing an old friend to remember how unimportant politics is.

So, until 8 June and a good few weeks after, I’m coming off Twitter and Facebook — after I’ve posted this article.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in