‘The dripping blood our only drink/ The bloody flesh our only food…/ Again, in spite of that, we call this Friday good.’ In spite of that. Anglo-Catholic convert T.S. Eliot knew a thing or two about Easter. The Passion story might end with resurrection and redemption, but it’s a celebration that we achieve in spite of agony, torture and abandonment, a tale whose root lies in the Latin ‘passio’, meaning suffering.

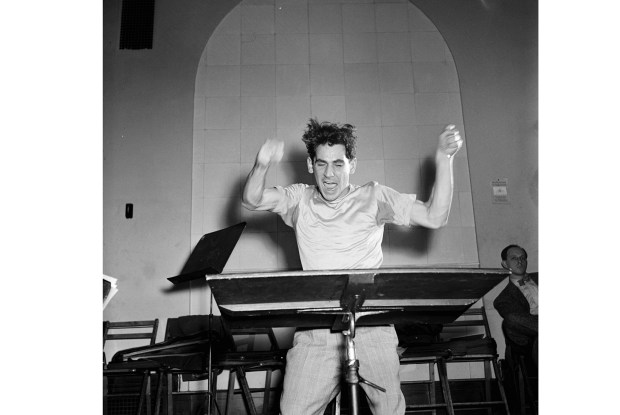

Musical Passion settings are no different — or shouldn’t be. A performance of Bach’s St John or St Matthew Passion should disquiet, even distress, as much as it consoles. But concert performances have become a comfortable festive tradition to slot in somewhere between buying the children’s chocolate eggs and cooking the roast — a Messiah with extra thorns — while now-ubiquitous stagings are simply opera-lite. A Passion that can find its humanity and not just its ritual beauty, that can transform an audience into a congregation, is a rare thing, but one Mark Padmore and the Britten Sinfonia achieve in their skilful reimagining.

This is liturgy for a secular age. Simon Russell Beale opens proceedings with St John’s Gospel, reading excerpts from Psalm 22 (‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?) and Eliot’s ‘Ash Wednesday’ in place of the central sermon. But he is no priest, and his readings offer no answers. Their texts tangle and tumble under the weight of doubt and human fallibility, and the anger of Russell Beale’s delivery makes clear that he too is a suppliant, not a confessor.

His presence on stage throughout the performance is powerful — an onlooker to the Passion story, who watches from a distance as we do, involved but forever separate. When the performance ends with Jacob Handl’s exquisitely simple motet ‘Ecce quomodo moritur’ (an addition suggested by the St John’s Passion original liturgical context) it is sung not just by the choir but the entire orchestra and Russell Beale, a collective statement that breaks the frame of the Passion with outstretched hands.

The choir itself is made up of just 12 singers. They serve as chorus, characters and aria soloists — no small musical feat (especially in the case of Evangelist/director Padmore) but one that makes such sense of Bach’s musical statement. A Passion is neither an oratorio nor an opera, it both enacts and reacts, commentates and emotes, and this duality is reflected in this musical role-sharing. With each aria it’s as though an individual steps forward from the crowd, sharing their story, before merging back into the mass again.

Musically it makes for a leaner, rougher performance than some, but one all the better for its lack of gloss. It’s a tone set by Padmore. Whereas an Evangelist like James Gilchrist has the sense of an other-worldly emissary about him — sympathetic, but removed — Padmore is an everyman. Flawed and urgent, fallible and human, he too is implicated in this collective act of violence. We see this mirrored in Eamonn Dougan’s laconic Pilate, whose heartbreaking ‘Betrachte, meine Seele’, coming immediately after the scourging, has a newly complicated friction to it.

There are moments of beauty — Zoe Brookshaw’s sweetly sung ‘Ich folge dir’ and Elinor Rolfe-Johnson’s luminous ‘Zerfliesse, mein Herz’, Reiko Ichise’s obbligato gamba in ‘Es ist vollbracht’ and the gentle rocking chorus ‘Ruht wohl’ — but they are tempered by plenty of grit, including a brilliantly jobs-worth quality to the fussy, fugal writing of ‘Wir haben ein Gesetz’. To say that it’s a relief when the performance finishes would, in most cases, be a criticism. Here it is praise for a Passion that brings the church into the concert hall.

The reverse was true of David Skinner and Alamire’s Good Friday concert at St John’s Smith Square — it’s headlining ‘premiere’ by Thomas Tallis a secular co-option of his magnificent, 18-minute motet ‘Gaude gloriosa’ for propaganda purposes by Katherine Parr. Discovered in manuscript fragments hidden in the walls of an Oxford college during the 1970s, this contrafactum (a Renaissance version of One Song to the Tune of Another) was performed here for the first time in almost 500 years.

Designed to rally the British people into a war-like spirit in support of their embattled king, ‘See, Lord, and Behold’ is an awkward fit for Tallis’s spacious anthem. Where the original is meditative and jubilant, dissolving its short text into endless arching melismas, Parr’s reworking is choppy, chattering and clattering with wordy invective. The effect is underwhelming, all the more so when set against a first half of Tallis’s very greatest Latin works including the tectonic grandeur of ‘Miserere nostri’ and the heart-tugging chromaticism of the penitential ‘In ieiunio et fletu’. We might have opened with a miracle in ‘Videte miraculum’, but sadly in ‘See, Lord’ we did not end with one.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in