It sometimes feels like our society has long abandoned its sense of individual responsibility. Flick open the papers or scroll through your newsfeed after yet another terrorist incident in Europe and it’s not uncommon to see headlines like ‘vehicle kills three’ or ‘truck attack claims casualties’. Damn those evil jihadi automobiles. This is why we need extreme vetting to prevent radicalisation in our parking lots.

Drinking and Violence

Of course, no one would genuinely suggest banning cars or trucks from the roads. That would just be silly. We know it’s the gimp behind the wheel who is responsible and not inanimate vehicles – the same vehicles driven by millions of innocent drivers worldwide. And yet this is the attitude our public policy makers apply to alcohol. Phrases like ‘Alcohol-fuelled violence’ become a focus with some attention paid to the second part of the phrase but a majority of it focused on the first. We rush to impose ‘lockout law’ zones in Sydney, destroying our once vibrant city’s nightlife in the name of protecting people from themselves.

All the while, countries like those of Europe, with far more relaxed alcohol and alcohol establishment laws than ours experience lower rates of violence. These are often countries where children share their first drink with their parents at an earlier age. Never do we stop to think about whether it is our drinking culture and not our drinking itself that is the problem. Never do we take a more than skin-deep look at what has shaped our drinking culture this way.

Because if we did, we might see that a culture that blames its problems on an external substance more than individual responsibility actually normalises the link between drinking and violence – providing an implicitly socially sanctioned excuse for individuals to engage in otherwise anti-social behaviour knowing that their drinking is a convenient excuse.

These are not merely propositions in theory. A report to the European Commission found that alcohol’s effects on behaviour are primarily determined by socio-cultural factors, including “culturally determined beliefs about the effects of drinking” and not the intoxicant’s chemical effects.

Damningly, Kate Fox, Anthropologist with the Social Issues Research Centre, notes that cultures like those of Latin America and the Mediterranean where people tend to hold positive beliefs and expectancies about alcohol, do not deal with nearly the same levels of alcohol-related anti-social behaviour as countries like the USA, UK, Australia or those of Scandinavia where public discourse focuses primarily on alcohol’s negative effects and where alcohol is often seen as a license to engage in behaviours the individual might otherwise avoid such as violence, promiscuity, aggression or other reckless, “out of character” or seemingly impulsive acts. She says:

This variation cannot be attributed to different levels of consumption – most integrated drinking cultures have significantly higher per-capita alcohol consumption than the ambivalent drinking cultures. Instead the variation is clearly related to different cultural beliefs about alcohol, different expectations about the effects of alcohol, and different social rules about drunken comportment.

These findings are confirmed by a 2008 report from the International Center for Alcohol Policies which found that the ‘license to transgress’ pervading our culture means that drinkers are ‘expected’ to alter their behaviour – engaging in varying degrees of conduct that is otherwise under relatively strict social constraint. Not only do these cultural expectations influence drunken behaviour, they also allow culprits to excuse their own behaviour through subsequent rationalisation and justification that they were ‘different people’ divorced from their own actions under the influence of alcohol.

Unfortunately, these aren’t lessons we intend to learn any time soon.

Plain packaging for alcohol?

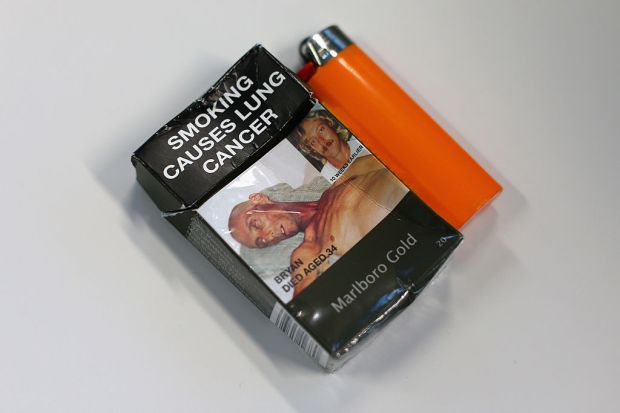

The latest in a string of hair-brained ideas is a call for ‘plain packaging’ laws to be applied to alcohol as a way to discourage alcohol abuse while highlighting alcohol’s supposed link to cancer in the same vein as tobacco products by featuring graphic imagery.

Never mind that graphic imagery only simplifies and dumbs down a complex problem by ignoring the multitude of factors that are actually key to an individual succumbing to cancer or other illnesses. These include genetics and family history, environmental factors, and behavioural variables, as well as social factors and consumption levels far outside the normal range.

Never mind that leading economists have found that household levels of tobacco consumption have actually risen since plain packaging of tobacco products was introduced in Australia – when statistics are adjusted for external factors such as price effects and an existing long-term downward trend in smoking levels over the last six decades.

Making things worse

Interestingly and worryingly, the tobacco plain packaging laws have been linked to a spike in market share for cheaper ‘low cost’ cigarettes with the trend confirmed by industry monitor InfoView, which found a rise in the market share of cheaper cigarettes from 32 per cent to 37 per cent in 2011 following the introduction of the plain packaging laws.

This highlights a deep flaw in the reasoning of plain packaging advocates – that a decline in household ‘expenditure’ as opposed to ‘consumption’ cannot be hailed as evidence for the policy’s success. This is because the removal of unique branding allowing for product differentiation and marketing only means that cheaper versions of the product become more attractive to consumers, actually connoting increased consumption for the same monetary expenditure.

Apply these principles to alcohol consumption and it’s easy to see how plain packaging could actually encourage immoderate and irresponsible drinking as well as a greater focus on alcohol as a generic intoxicant rather than a range of products associated with varying degrees of enjoyment due to differences in taste, texture and brand image – forms of enjoyment that do not call for immoderate or irresponsible behaviour.

What’s more, this type of change to market and consumer demand actually incentivises the production of more cheap alcohol, with smaller brewers and other small or medium alcohol manufacturers encouraged to shift resources into boosting their economies of scale to get their customers as wasted as possible on as low a price tag as possible given that they will no longer need to be concerned with long-term investment in building a unique brand image. Rather, price will become one of the only meaningful ways for companies and products to distinguish themselves and attract consumers.

The final kicker to all this? The claim that household expenditure on tobacco has fallen after plain packaging was introduced has also been exposed as patently false even when the government’s own ABS data is used, as noted by leading RMIT University economist Sinclar Davidson.

France

The failed plain packaging experiment was most recently co-opted by France which had to pay tobacco companies over 100 million euros as compensation for branded products that could no longer be sold when their new law was introduced. For all their effort and money, they were only rewarded with Irony as French smokers responded by purchasing and consuming more tobacco this year after the law was enforced.

At the end of the day…

It’s abundantly clear that moves to punish or discourage substance consumption through laws such as plain packaging, lockout laws or even sin taxes are often ineffective at what they do. It’s also clear that they can often backfire and have the opposite of the intended effect. As such, they are the wrong answer.

But that doesn’t mean that they aren’t a quick or easy answer. Like a Band-Aid applied to a fracture, they offer politicians and policymakers the opportunity to appear tough on complex social issues without doing anything meaningful to address the underlying socio-cultural factors.

Meanwhile, the rest of us can sit tight and watch our freedoms and choice get taken apart.

Satyajeet Marar is a Sydney writer and Research Associate for the Australian Taxpayers’ Alliance. He can be followed on Facebook.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in