‘It was easy, it was cheap, go and do it,’ sang the Desperate Bicycles on their self-funded debut single in 1977, summing up the punk belief that you didn’t have to be the world’s best musician before getting up on stage or making a record. Twenty years earlier, a previous generation learned a similar message from the skiffle explosion, which put guitars in the hands of many future members of the key British rock groups of the Sixties. It therefore seems appropriate that a musician first inspired by seeing The Clash has eventually written a book about skiffle.

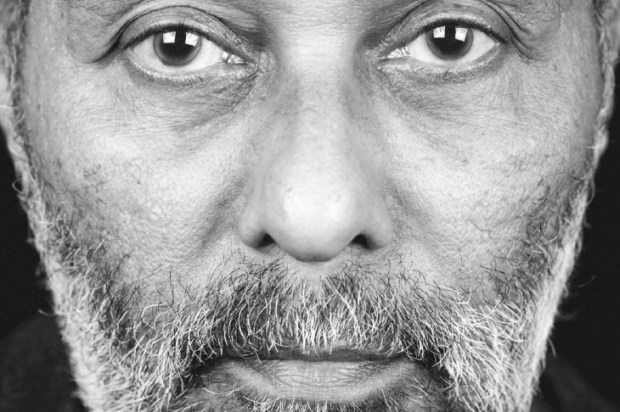

Billy Bragg has a long-standing interest in the genre, and his passion for those early days of frantic strumming and washboard-driven rhythms is clear throughout his eloquent and thoroughly researched book. A hybrid musical form, skiffle had its roots in the jazz which developed in the wide-open Storyville district of New Orleans, but it also contained elements drawn from the blues, the protest songs of Woody Guthrie, prewar hillbilly tunes, prison work songs and the folk music of the British Isles and of Ireland.

Lonnie Donegan, the undisputed king of the movement, found his big opportunity while playing as a sideman with Chris Barber in Ken Colyer’s Jazzmen, stepping into the spotlight as part of a stripped-down ‘breakdown group’ at their shows, performing what was billed as a ‘skiffle’ session during intervals.

As for the word itself, Bragg quotes Paul Oliver’s landmark 1969 work, The Story of the Blues, to the effect that ‘skiffle’ was a 1920s term for those impromptu gatherings more commonly known as rent parties. How-ever, other jazz scholars have credited Emile ‘Stalebread’ Lacoume’s pioneering 1890s New Orleans street combo the Razzy Dazzy Spasm Band as a skiffle group, and a 1936 interview with Lacoume highlighted their defiantly makeshift instrumentation, foreshadowing that of some 1950s skiffle bands, ‘turning a half beer keg into a bass fiddle, a cigar box into a violin, a soap box into a guitar’. Here was the DIY spirit in its purest form. Reaching further back, a 1873 dictionary of Somerset slang published in London defined ‘skiffle’ as ‘to make a mess of any business’, and ‘skiffling’ as ‘the act of whittling a stick’.

Bragg draws an impressive number of strands together, telling the rich tale of a country still experiencing the final years of postwar rationing, in which teenagers began to assert themselves and develop their own interests — a world of trad jazz, dance halls, CND marches, coffee bars and the first stirrings of the American rock’n’roll movement which eventually swept all before it. As might be expected from a man who has often written and sung about politics as well as matters of the heart, he is particularly good on the various left-wing and occasional communist affiliations of some in the skiffle scene. However, it has to be said that these tended not to be the people who went on to have the hits.

Although skiffle arose out of the British jazz world of the early 1950s, where the sound had been largely based around the ensemble playing of wind instruments, it eventually brought the previously overlooked guitar forward and placed it centre stage. Most musicians who joined skiffle groups and went on to fame didn’t grab a trumpet and form a trad band; they picked up a guitar, learnt three chords, and started a rocking combo. Significantly, when John Lennon’s skiffle outfit The Quarrymen made their July 1958 demo disc, it was Buddy Holly they covered, not Lead Belly. The more acoustic slant of early skiffle musicians had mostly a practical origin, since solid-bodied electric guitars were all but unobtainable in the UK. (Hank Marvin owned the first Fender Stratocaster in the country, which Cliff Richard bought for him on a trip to New York at the late date of 1959.)

Despite Bragg’s usually excellent research, ‘Peggy Sue’ can’t be described as Buddy Holly’s debut single (that was the excellent ‘Blue Days, Black Nights’, which appeared 18 months earlier, and there was the worldwide hit ‘That’ll Be the Day’ in between, credited to The Crickets, a record company ploy which fooled no one). Similarly, the phrase ‘Teddy Boy’ was not coined by a 1954 Daily Sketch headline writer, but passed into the language following a murder trial report in the Daily Express in September 1953, which said of the drape-suited teenage gang concerned, ‘They became “The Edwardians” or — as their girlfriends preferred it — the “Teddy Boys” ’.

As for the political inspiration or otherwise of most early skifflers, it’s more likely to have been similar to that in the punk days, summed up by Steve Jones and Paul Cook of the Sex Pistols, who told the NME in 1977, ‘We’re only in it for the beer and the birds after the show’. Which, after all, is probably not too far from the original impulse of many Storyville musicians a little over a century ago in New Orleans.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in