One fail-safe test of a writer’s reputation is to see how many times his or her books get taken out of the London Library. Here, alas, John Lodwick (1916–1959) scores particularly badly. If The Butterfly Net (‘filled with a lot of booksy talk and worldly philosophising,’ Angus Wilson pronounced in 1954) has run to all of five borrowers in the last five years, then The Starless Night (1955) seems not to have left the shelves since 1991. All this suggests that the title of Geoffrey Elliott’s valiant attempt to reconstruct Lodwick’s lost, vagrant and sometimes violent life is painfully accurate.

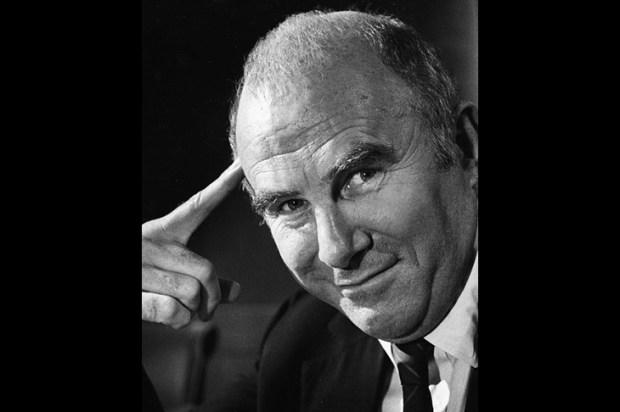

Why should this writer, who published nearly a score of well-regarded novels before dying in a Spanish road accident, have fallen so irretrievably off the map? It was Cyril Connolly who remarked that those whom the gods wish to destroy they first endow with promise; and the sparkle of The Cradle of Neptune (1951), an account of a deeply unhappy apprenticeship at Dartmouth Naval College, was there for all to see. Somerset Maugham approved; Anthony Powell, reviewing it for the TLS, allowed the presence of ‘notable gifts’. But there were also complaints about unevenness and imagination taking second place to the roman à clef.

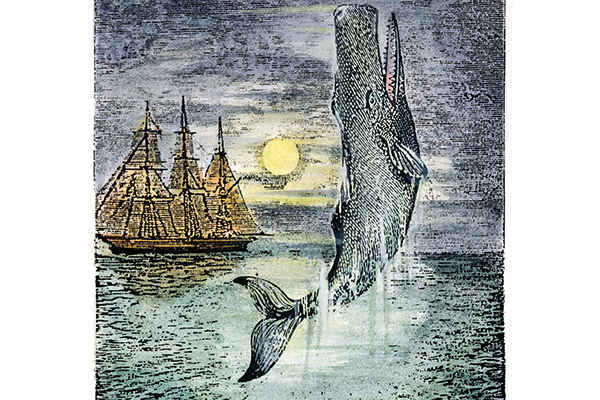

The autobiographical shadings of Lodwick’s oeuvre make regular appearances in A Forgotten Man, if only because so little of his fraught existence is there to be reconstituted. The subject admitted to three marriages (there may well have been four) and while Elliott is on firmish ground with a childhood spent in India and at his grandfather’s house in Cheltenham — Lodwick senior was killed by a German U-boat — a prewar sojourn in Dublin is more or less beyond recovery. Only in 1939–45, when Lodwick served successively in the French Foreign Legion, the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and a Commando Unit, blew up fuel depots in Crete and ended up in a Serbian POW camp, is there any sense of a distinct personality looming up through the murk.

As for the figure who emerges from this riot of rumour, hint and tenuous imbrication, the SOE director’s verdict is worth quoting in full:

This is a plausible, well-spoken but unscrupulous young man. He is only interested in his own skin and that of any woman he might admire. He struck me as being a soldier of fortune chiefly for such glamour as might be derived from a lucky VC etc.

Lodwick’s ‘moral integrity’, meanwhile, was graded at ‘– 0 per cent’. A course commander’s report from 1942 rates him dauntless and devil-may-care, but also ‘objectionable… conceited, arrogant and intolerant of others who do not do as well as himself’.

If Lodwick’s egotism and his tough-guy ancestry were always likely to impede his rackety progress through the postwar world — The Butterfly Net is, among other things, a resumé of some of his difficulties with publishers — then they are also the two things that make him interesting to a modern audience. In an era already tending to institutionalised drabness, he belonged to an all-but extinct part of the literary demographic — the writer as man of action, who fights (none too scrupulously, on this evidence) in wars, explores far-flung climes as a traveller rather than a tourist and, perhaps inevitably, leaves behind a personal myth that is almost as enticing as the shelf-full of books.

Geoffrey Elliott does his best for Lodwick, offers context when data ebbs and can be forgiven for making more of his chance encounters with famous contemporaries than is warranted by the stark record of their association. His dealings with his ‘friend’ George Orwell, for example, were limited to a single meeting and I didn’t believe for a moment that Evelyn Waugh — again, met in the course of a brief wartime interview — mangled his name to produce the character of ‘Corporal-Major Ludovic’ in the Sword of Honour trilogy.

It is a pity, too, that Elliott should confine himself to a non-literary study and reproduce other people’s criticisms of Lodwick’s dense, doomy romanticism rather than tell us what he thinks himself. All the same, the impulse that tugged him Lodwick’s way can only be applauded. Literary orthodoxy nearly always insists that the 1950s were the age of Movement poets and Angry Young Men. Not the least of A Forgotten Man’s achievements is to remind us that there were other literary lives being lived out on its margin — wild, exotic and professionally adrift.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in