For those of us who exist long enough it is all too easy to live on somehow through decades of fashionable thinking which then seem, in retrospect, hard to believe have ever occurred. Did people once really think or speak like that?

As the years go by will we willingly credit, for example, that very large numbers of people apparently believed passionately at one time in global warming (on somewhat limited evidence) and not only founded political parties based on such credence but even proposed doing disagreeable things to so-called ‘deniers’?

That last bit wasn’t even particularly far in the past.

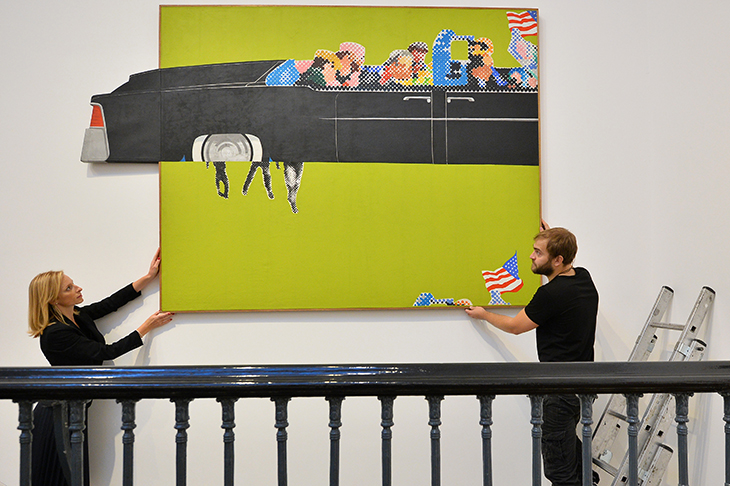

When I was a young adult starting out on what I hoped would be a rewarding career as a professional painter almost everyone else spoke or wrote complete nonsense probably because what we were dealing with seemed nothing more important than some obscure cultural concept.

After years of suffering such folly with reasonable grace I even felt obliged to begin writing myself as well as collecting examples of the then totally impenetrable writing of others. Foreseeably, my modest volume The Art of Self Deception quite soon followed the general fate of such books yet not before making me aware of something of apparent importance which was happening on the other side of the Atlantic. Indeed, rather a beautiful American girl who happened to work at the London gallery which exhibited my paintings soon set me right on the staggering number of politically incorrect instances she had detected in my book. Those were indeed her sole interest in the matter.

Politically incorrect? Was there really a blissful time in my life when I had never even heard those words?

Not long afterwards I was offered a part-time job at an outer London art school based largely on a senior lecturer’s liking for my book. But the job carried an important condition: I was obliged to promise I would never say more than yes or no to any question put to me by the school’s principal or his deputy. Shades of the wartime practice of providing the enemy with name, rank and service number only perhaps? In that way such people could hardly dismiss me as they would undoubtedly have done if they had had even a hint of my real opinions. By such means I survived four years where worthier predecessors had barely lasted a term. Other than in our Fine Art Department just about every fashionable post-modernist idea was rife by then at the school. For example, all staff were asked to believe that almost all women’s names had been deleted deliberately from the entire historical record of Western art through the actions of hopelessly ‘jealous’ males. Indeed, as I was soon to be told by female students when visiting other art schools: ‘My artwork challenges the existing patriarchal paradigm’. Did people ever really talk like that? They did.

Thus far I had only really brushed shoulders with political correctness and feminism yet the full panoply of post-modernism was already busy uncoiling itself even in dozy old England. Multiculturalism, post-colonialism, environmentalism, gender issues, deconstruction, post-structuralism, critical studies, conceptual art… might life ever simply just be worth living again?

The basic purpose of post-modernism, of course, is to demonstrate that everything the human race did prior to its advent was entirely misguided. That was why education, for example, supposedly required urgent politicising and a complete spring clean. Did anyone ever bother to explain the origins of conceptual art to you? The basic idea was to deprive art dealers of tangible objects with which to trade, thus hurrying the supposedly desirable death of capitalism.

Strangely enough the kind of art I once practised and taught myself is and was inherently satisfying – as playing a musical instrument properly can be.

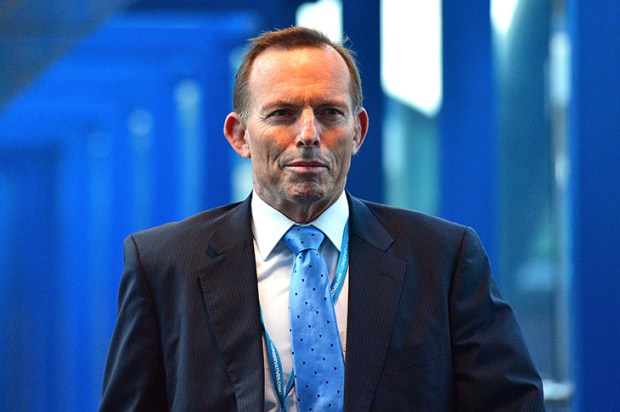

Post-modernist values sound good, of course, while generally proving fatal for much of the human race in practice e.g. multiculturalism. Thus for much of its entire history the human race has preferred the company either of its own kind or of people at least broadly sympathetic to its values. Immigration of other kinds usually creates ghettos or other forms of social chaos. Indeed in the case of much of Europe it has recently created that historically irreplaceable continent’s imminent demise. If you haven’t read Douglas Murray’s The Strange Death of Europe (2017) repair such deficiency as soon as you can. Can Australia learn from that book’s findings? It would be heartening to believe so.

For the latter half of my adult life I have had a largely inexplicable desire to write a book called Slow Train to Idiotsville not simply because of the title’s appeal but because I see it as an apt metaphor for what we have recently been doing to ourselves. Modernism, which brought with it an often empty rhetorical language, was hard enough to endure but subsequent decades of post-modernism have proved much worse. Peep over the edge of the crater then take a long, satisfied look at the complexity of the rivers, valleys and fertile lands which lie below the apparent peak. In other words, ordinary life can be deeply satisfying. By contrast, our post-modernist world has already become deeply depressing for far too many people – just witness the insatiable use of drugs by Australia’s young.

I spent my own nineteenth year on the front-line between the Russian and British forces in Northern Germany. Much of what we practicsed involved our immediate reaction in the event of a Russian attack. Even the threat of war jolts some people into a proper and generally overdue sense of reality.

But have we in Australia not already passed the sensible hour for this whole country to wake up?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in