Aren’t you getting a little sick of the white cube? I am. I realised how sick last week after blundering around White Cube Bermondsey, where the walls are so pristine no label is allowed to sully them, struggling to work out what I was looking at. I was reduced to photographing the works in order and tracing my itinerary in ink on the ground plan — shoot first, ask questions later — and even then I had to keep getting the attendants to tell me where exactly on the plan I was. One of them admired my wiggly drawing. Well, it was a surrealist exhibition.

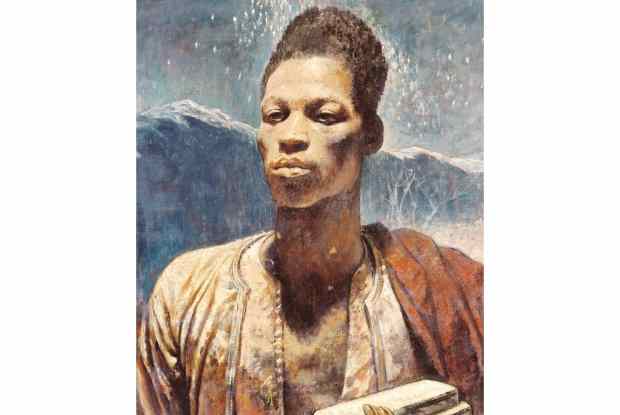

Dreamers Awake sets out to repossess surrealism for women. In place of the ‘decapitated, distorted, trussed up’ female body that was the object of male surrealist fantasy, curator Susanna Greeves hopes to show ‘the symbolic woman of surrealism…refigured as a creative, sentient, thinking being’. Eighty years on from Meret Oppenheim’s fur teacup, do we need proof that women can do surrealism? Shows of ‘women’s work’ are tricky territory. The Saatchi Gallery succeeded with Champagne Life in 2016, but that was smaller: 18 artists to Dreamers’ 50. It was also more diverse, as it had no theme.

Despite surrealism’s claims to free the imagination, its vocabulary is limited; there are only so many ripostes to male erotic fantasies a girl can make. Decapitation, distortion and trussing feature prominently in this exhibition, whether repossessed or not it’s hard to tell; there are more penises and fewer breasts than in the male repertoire, but plenty of vulvas sculpted in bronze, carved in wood and teased out of pieces of fur and pubic hair. All the obvious names (Meret Oppenheim excepted) are represented, not always by their best work. There are some wickedly witty Leonora Carringtons, but the late great Louise Bourgeois is ill served by a series of flabby collaborations on drawings with Tracey Emin, and the stuffed dummies contributed by contemporary queen of the uncanny Berlinde De Bruyckere aren’t a patch on the sculptures of tortured tree limbs she is best known for. (Too gender-neutral for this show, perhaps.)

Among the repossessions, there are fresh approaches. Rachel Kneebone’s orgiastic bouquets of white porcelain body parts are always delectable and Carina Brandes’s black-and-white photographs of animal-human transformations feel genuinely dangerous. Paloma Varga Weisz’s pathetic drawings of balding male Giocondas with multiple breasts give tit for tat to the male surrealists, while Man Ray’s muse Lee Miller — singled out by Greeves as ‘surely the most objectified woman of surrealism’ — contributes the show’s most stomach-churning image, a photograph of a severed breast on a plate.

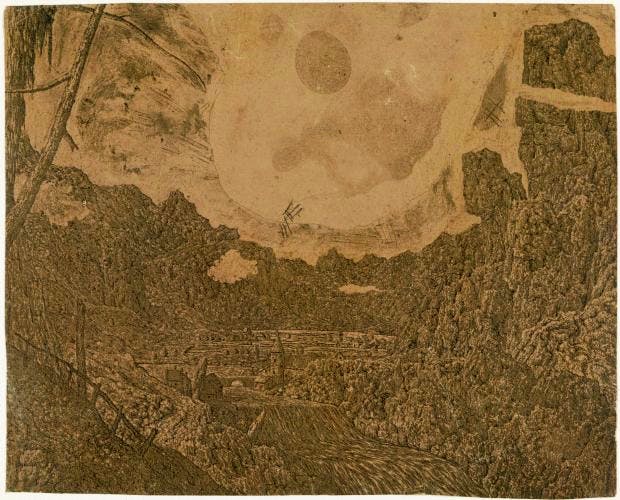

Man Ray is the inspiration for A Handful of Dust, another themed exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery on a more universal subject. The surrealist photographer’s 1920 image of Duchamp’s interrupted work in progress, ‘The Large Glass’, coated in dust and looking strangely like an aerial photograph (see p.29), is the cue for curator David Campany’s eclectic meditation on the dust we are, and to which we shall return.

When man-made, as at Hiroshima or the Twin Towers, dust is a moral issue, though not when attributable to acts of God such as eruptions of Vesuvius. Still, a collection of American commercial postcards manages to turn the dust storms of the 1930s into a tourist attraction: ‘Find the image in the dust cloud,’ challenges one, while another advertises a café with the caption ‘We stopped at Bradford Cafe and Novelty Shop, 719 N. Fillmore, Amarillo, Texas’ under a photo of a filthy car and billowing dust cloud. But the clear winner in the dusty-car stakes is Mussolini’s Lancia, photographed after ten years of accumulating dirt and two million lire of unpaid parking fees in the Milan garage where it was dumped in 1945 after its owner was dragged from it and shot. Beside it a handsome young mechanic in spotless overalls studies the dirt left on his fingers after swiping his hand over the bonnet; the licence plate is missing but the number is written in the dust.

Documentary photographs are the stars of this show: conceptual wheezes like Eva Stenram’s mingling of domestic with cosmic dust by rephotographing dust-coated Nasa images of Mars and naming them ‘Per Pulverem Ad Astra’ (2007) can’t compete with the poignancy of Robert Burley’s photograph of workers watching the demolition of the Kodak analogue film factory in Rochester, New York in 2007 and recording it on the digital cameras that had cost them their jobs.

My only niggle about this intriguing show is the white-cube factor: even in the irremediably artsy-craftsy spaces of the Whitechapel the ambience feels too clinical for the subject. What happened to the lovely old dusty galleries recalled in the 1970s polaroids showing self-appointed pop-up cleaner Robert Filliou cheekily wiping dirt off Old Masters in the Louvre with a duster? I longed for a speck of the real thing.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in