Boris Johnson’s Australian charm offensive will not unscramble the egg. Nor will seeking to love-up the old Commonwealth after divorcing Europe change what Professor Goldsworthy has described as a lingering sense of ‘a sort of betrayal of Australia’ resulting from its 1973 EEC nuptials. When knocking back Britain’s two-year long attempt to join the Common Market back in the early 1960s, President de Gaulle believed that ‘Perfidious Albion’s’ attempt to get a special deal for the Commonwealth was really aimed at destroying the six-member union from within. And when Britain eventually did join the EC in 1973 by reneging on repeated undertakings to its former colonies, Australia was inclined to agree with the de Gaulle view of Britain.

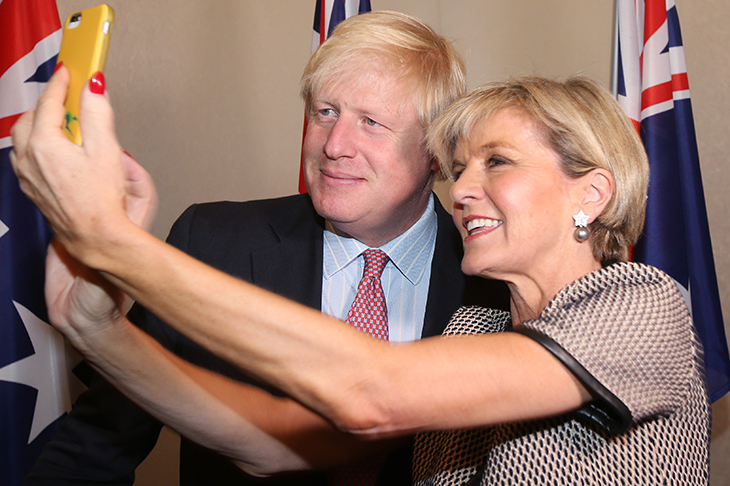

Boris is very good indeed at what he does; saying what his audience wants to hear. ‘Brexit will bring Australia and Britain closer together’ — just as Britain’s lurch into Europe half a century ago helped tear us apart. Britain is ‘going to be more committed to Australia and Brexit is really on the way’ despite the reported divisions within the Conservative government that Boris dismisses with ‘We are going to get this done and in style’ while Le Figaro cheers Britain’s consequently weakened negotiating position. But don’t hold your breath waiting for Boris’ promised Australia-Britain free trade deal and the open and generous visa regime for Australians travelling to the UK; as his ministerial colleague Phillip Hammond has said, nothing will happen until at least 2022. And while Britain may not have forgotten its ‘real friends’ in times of war and still retains some sense of nostalgia for its former empire (evidenced in a recent opinion poll favouring post-Brexit pro-Commonwealth trade deals), it has never let sentiment stand in the way of self-interest. Our being ‘towards the front of the queue for free trade deals’ is all very well, but whatever the platitudes, the old relationship is beyond resurrection.

Before Britain’s move into Europe, mutual dependency saw the UK taking almost 40 per cent of Australia’s exports in the mid-1950s (mostly in rural products) that has now evaporated to about one per cent; Australia bought almost 30 per cent of its imports from Britain but now takes only about two per cent. Yet the British drift towards Europe began years before — and leaving will not end it.

British concerns about its economic ties with Australia started shortly after World War II when it was clearly no longer able to remain the major source of Australia’s much-needed overseas investment funds. To avoid subjecting alternative sources of capital, like the US, from significant trade disadvantages under Empire Preferences, Australia’s Deputy Prime Minister Jack McEwen led the otherwise Anglophile Menzies government into what historian John Kunkel describes as deliberately moving Australia out of Britain’s economic orbit. This clearly prompted Britain’s Harold MacMillan’s view that ‘we need to re-examine the relative importance and future prospects of our trade with Australia’ and marked the end of UK resistance to closer ties with Europe instead of the Commonwealth.

But 1961-2’s unsuccessful attempt by Ted Heath to join the EEC (despite repeated assurances that nothing would be done to diminish Commonwealth economic links) brought ‘a sense of resentment about British perfidy. This relied on the notion that sentiment, tradition and ties of kith and kin should mediate fundamental clashes of economic interest’. As Trade Department head Sir John Crawford lamented, this represented a reversal of all previous declarations of policy, and was seen as ‘an affront to Australian (and British) concepts of fair play’. While the economic impact was not felt until EEC membership in 1973, the special relationship was destroyed by the Heath bid’s preparedness a decade earlier to dump Australia for Europe. Having covered the Heath negotiations in Brussels for Fairfax, I wrote a few years later in Quadrant: ‘They don’t call them “Poms” any more in the Dept of Trade — not even the almost affectionate familiarity of “Pommie Bastards”. Now it is the “Brits” — a sharp unpleasant word that reflects the new look in Australia’s trading relations with Britain’. For all his cuddly economic talk, Boris is a Brit.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in