In a few weeks, the Victorian parliament will consider a law change to permit assisted suicide. Is such a dramatic change in medical ethics necessary? How well have unintended consequences been recognised and thought through?

There have undoubtedly been problems in end-of-life care in the past. A reading of the 1,037 submissions to the recent parliamentary inquiry reveals many cases of a single family death, which has so upset family members that they think assisted suicide is an appropriate option. Many such deaths were decades ago, preceding modern palliative care. More recently, palliative care has often been under-used with the availability of the knowledge and skills limited by government under-funding.

Palliative care practitioners pay careful attention to control of any distressing physical symptoms, but also psychological and spiritual issues, for both patient and family. It is a whole-person type of care, assisting the patient and their family, as they navigate the journey of a terminal illness, which is unfamiliar to many.

No legal protection of doctors is necessary for good palliative care. There have been no doctors charged for providing appropriate palliative care medication to patients. That concern is a straw man.

Polls can be misleading. It is often stated that 80 per cent of Australians are in favour of assisted suicide: but what question were they asked? They have generally been asked something like: “If a person has a terminal illness, and has unrelievable pain/suffering, are you in favour of assisted suicide?” That is an unrealistic question, because that need not ever be the clinical situation. Pain management using a variety of tools is well advanced in 2017, and there is palliative sedation available if necessary.

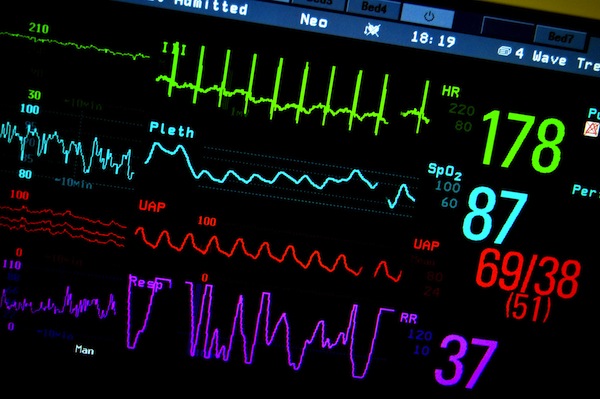

Recent research into the facts surrounding end-of-life decisions overseas reveals that the main reason for requests for assisted suicide is not poorly controlled suffering at all, but a desire to control the circumstances at the end of a life. It is the notion of autonomy which appears a driving factor in the preference of some to have an assisted suicide bill come before the parliament. Sometimes there has been too much medical technological interference with the last days or weeks, particularly in hospitals, which has driven a wish for more control in the manner of death.

The medical profession is quite divided on the issue. Private polls indicate in fact most doctors are opposed to law change. An opinion is only as good as the knowledge and experience informing it. The more doctors have to do with palliative care, the less they think assisted suicide is necessary.

How do we then think about and make decisions about such an issue?

It is necessary to look at available solutions broadly, and the effect of law change on the total community, and on the common good. There is an assumption that if this sort of legislation is passed, it does not affect anyone other than the individuals concerned. That is not the case. Changing the law will change it for everyone in the community, and has consequences which have been poorly recognised and understood. Even if some individuals were helped by assisted suicide, what is the price for the community and healthcare?

There is major concern about the adequacy of so-called safeguards, and the practical consequences of law change. It is not primarily, as sometimes alleged, a matter of religious belief.

Any safeguards in legislation around the world are inadequate in practice. Firstly, there is no consideration of the question “Why is this person requesting assisted suicide”? For any good clinician, that is the key question, and experience of clinicians is that people request assisted suicide when there is an unsolved problem. If the problem is solved, research is that they often change their mind. The good clinician would then interview and assess to determine what the problem(s) are, and what can be done about them. To just act on a request for assisted suicide and not make such a clinical enquiry, is plain bad medical care.

A doctor cannot tell you how long you have to live. Such estimates are guesswork. What ‘unbearable suffering’ is depends on what palliative treatment has been used, and the attitudes and messages which surround the patient. Notably assisted suicide legislation has taken hold in The Netherlands and Belgium, where palliative care was less well developed. If people around the patient give the impression that the person is a burden and a family do not adjust well to illness, one can easily see how a patient can request assisted suicide. Family members may be impatient and intolerant of illness. People feel a burden just because they are ill.

The door is opened to elder abuse and coercion. Unfortunately, when there is elder abuse, vulnerable ill people are usually abused by family members and can be made to feel a burden and unwanted very easily. It is virtually impossible to detect whether someone is being coerced by the attitudes of their family or their medical or nursing practitioners, some of which may be to do with financial gain (so-called early inheritance syndrome).

The criteria of the safeguards will inevitably creep, as they have in Belgium and The Netherlands, to include people with psychiatric illness and “being tired of life”, undermining mental health care. The complaint of advocates will be about ‘discrimination’. In Victoria, advocates are already lobbying for wider criteria to include any chronic illness, before a bill has even been presented to parliament. That would include psychiatric illness.

The admitted real agenda of prominent euthanasia advocates is unrestricted autonomy without consideration of the common good of the community, or its effect on health care. Some ethicists advocate the pairing of assisted suicide with organ transplantation.

Some former advocates in Europe have withdrawn from euthanasia processes and now warn against going down that path. Professor Theo Boer, a former supporter, appeared before the British parliament and warned them not to pass such legislation, and not to go down that path. The UK parliament overwhelmingly rejected assisted suicide legislation as unsafe, as have most jurisdictions around the world.

Dr Boudewijn Chabot, a European psychiatrist who euthanised a woman with depression many years ago, has now stated in the Dutch press that he is aghast at the rapid increase in people euthanised for psychiatric illness and early dementia.

Assisted suicide legislation would harm the care of future patients.

In The Netherlands and Belgium, it is becoming the expected norm that people should “get out of the way” because of a “duty to die” if they have a serious illness.

Assisted suicide would create a new cheaper type of medical “treatment”, which will inevitably be used by health bureaucrats to deny access to more expensive treatments.

Mixed messages about suicide will undermine public mental health messages. How will Beyondblue square messages which suggest people see their doctor for treatment of depression and suicidal thought if at the same time, we have people being told that if they have suicidal thought, the state will assist them to suicide, and without proper assessment? Will there be a Medicare number for euthanasia?

Ultimately, what sort of health care system do we want?

On balance, the risks to the common good and the unintended consequences of such legislation are sufficiently great that legislation of this nature should be rejected, as it has been in Britain, New Zealand, and most other jurisdictions. The World Medical Association has a formal policy that regards assisted suicide and euthanasia as unethical.

The reason for rejection of assisted suicide and euthanasia legislation is that it is unsafe for the community. Once this ethical line is crossed, it leads to a deterioration of medical care.

Legislation which may benefit a small number of people has a price which is too great for the community, especially when there are alternative medical and non-legal measures available.

Is it better to set up an assisted suicide bureaucracy, or fund palliative care properly?

It is essential though, at the same time as we reject a legislative approach as unsafe, that palliative care knowledge and skills be more widely disseminated. To enable people to use existing professional palliative care expertise and services by appropriate referral, the state government should expand training and funding, not restrict it.

Dr John Buchanan is a former Chair of the Victorian Branch of the Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. He has worked as a physician, then medical director, at Citimission Hospice Program and after training in psychiatry as a liaison psychiatrist, oncology and palliative care, in Melbourne. In 2013 he was the recipient of the RANZCP Medal of Honour.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in