Newly released government data has confirmed that more people smoke in Australia than they did in 2013. This is despite Australia being home to the world’s most expensive cigarettes and world-first plain packaging laws. The National Institute of Health and Welfare survey found that more than 20,000 Aussies smoke today than they did in 2013, and comes a year after the release a report from major accounting firm KPMG (commissioned by Philip Morris International, Imperial Tobacco and British America Tobacco Australia), which found that Australia’s tobacco black market is a billion dollar+ industry and accounts for more than 13 per cent of all cigarettes consumed.

These findings make clear what we should have known for a long time – that simply pushing hard-line tobacco control policy delivers limited and diminishing returns, despite the political convenience it presents for our leaders.

Some historical context – tobacco smoking has been in long-term decline since the sixties, primarily since that was when information about the severe health risks of tobacco smoking first became widely known. This was followed by a proportionate response – public information campaigns, surgeon general warnings and tax hikes to reflect the burden that tobacco places on our healthcare system. Australia was no exception and smokers have been in decline until 2013.

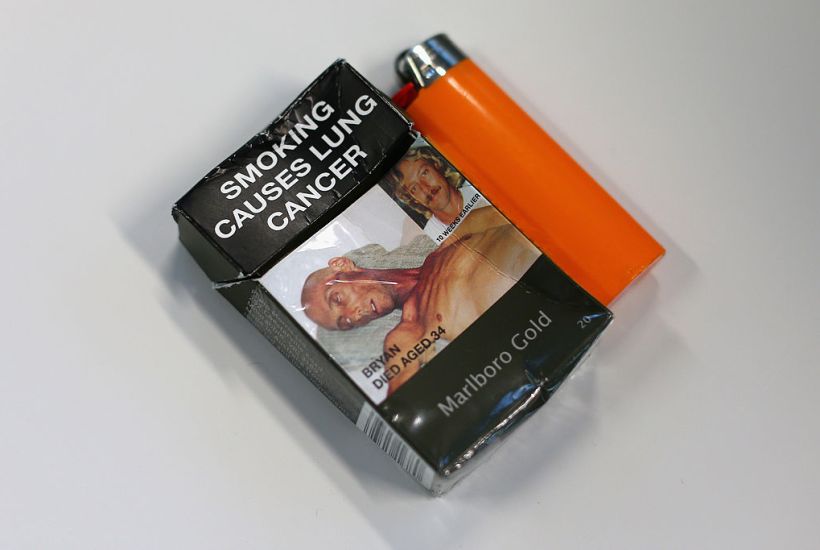

In 2006, the now familiar graphic imagery of pus-filled lungs and deceased bodies became a common feature on durry cartons across the country and in 2012, the Gillard government took things a step further by introducing ‘plain packaging’ – ensuring that tobacco companies could no longer use their logos or branding by forcing them to sell their products in generic containers.

The policy has since been touted as an overwhelming success by the government and tobacco control lobby, who have credited it as an international success story in the war against the tobacco scourge. Unfortunately, the evidence doesn’t quite add up.

A report from Sinclair Davidson, Economics professor at RMIT found that when adjusted for tax refunds and the timing of the policy’s introduction, tobacco excise actually went up by 0.5 per cent in the wake of plain packaging’s introduction. And it isn’t hard to see how removing branding could actually encourage tobacco consumption – when branding and marketing is removed in an industry where actual product differentiation isn’t significant, people are likely to choose between generic products based purely or primarily on price. This was confirmed by the research, which found that the market share of cheaper tobacco products has actually gone up in the years following plain packaging, encouraging tobacco companies to produce cheaper products on a wider scale. It’s no wonder then that Australasian Association of Convenience Stores chief executive, Jeff Rogut has revealed that the most common questions received from customers by member stores in recent years is “what is the cheapest pack of smokes you’ve got?”

Other government statistics offer little respite. In the first year since the introduction of plain packaging, the ABS found that household expenditure on tobacco rose, state departments found a rise in the smoking prevalence rate and even youth smoking rates went up slightly according to the National Drug Survey.

The same pattern has followed in France, which introduced plain packaging in January this year. Since then, more cartons of cigarettes have been sold compared to the same time frame last year when branding was allowed, according to the French customs office. Though it is too early to conclusively say the policy has failed in France, the outcome still doesn’t look promising in light of the Australian experience.

But surely making tobacco packets as unappealing as possible is a good thing and encourages people to quit? This is true; indeed a 2015 study found that consumers perceive the cartons as unappealing and discouraging. However, this is largely due to the graphic health warnings themselves, which have existed since 2006 – you hardly need an expensive study to tell you that most people find decomposing human organs to be somewhat off-putting.

Yet even the drop in smoking since 2006 is consistent with a wider trend of a long-term drop in smoking which started years before and has been driven primarily by understanding about the risks of tobacco as new generations reach adulthood and steadily creeping tobacco excise. The effects of plain packaging must also be isolated from those of graphic health warnings for its effectiveness to be fully assessed and even the government’s commissioned independent expert has admitted that this is impossible.

The case against plain packaging ultimately goes beyond its pragmatics and touches on principle. The policy represents government appropriation of intellectual property rights under the guise of paternalism with doors open for the same principle to be used to argue for plain packaging of alcohol, fast food or anything else deemed a public enemy. This is especially problematic where the policy is dubious in its effectiveness.

Satyajeet Marar is the Director of Policy at the Australian Taxpayers’ Alliance and the Director of MyChoice Australia

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in