The Red-haired Woman is shorter than Orhan Pamuk’s best-known novels, and is, in comparison, pared down, written with deliberate simplicity — ostensibly by a narrator who knows that he is not a writer, but only a building contractor. Polyphonic narratives are replaced by a powerful, engaging clarity. This simplicity is the novel’s greatest strength, yet at certain points seems as if it might become a weakness.

Part one, which takes up the first half of the book, is superbly concentrated. It describes one summer in 1986 in the life of Cem, a middle-class 16-year-old boy who takes on a summer job 30 miles outside Istanbul to earn money before cramming for university entrance exams. Ignoring his mother’s misgivings — his father, a pharmacist and political dissident, has gone missing — he joins a master well-digger as his apprentice.

The episode evokes the disturbing intensity of adolescent experience. Cem’s unformed character shimmers in the disorientating heat: he is capable of being both frightened and foolhardy, both meek and rebellious.

Master Mahmut has his own mystique. In Turkey, where water is priceless, a digger of wells is traditionally revered. Mahmut, using his ancient skills, stubbornly insists upon digging down in an unpromising barren plateau. As Mahmut and Cem excavate, metre by hard-won metre, the bond between them becomes central. Mahmut, it is made clear, becomes a father-figure to fatherless Cem. But his tender attentions are edged with domineering brutality:

When helping me to bathe, Master Mahmut, half out of concern and half to tease, would press his thick coarse fingers into any bruises he spotted on my back; and when I shuddered and groaned ‘Ow’ in response, he would laugh and tell me tenderly to ‘be more careful next time’.

Cem, in return, responds to the evening fables recounted, father-fashion, by Mahmut by telling the tale of Oedipus, with its implicit threat.

The well itself casts a dark gravitational pull. Wells are always both sinister and life-giving: it is no accident that in Japan they are seen as gateways to the underworld. In Pamuk’s earlier novel, My Name is Red, the murdered body of the miniaturist is thrown down a well. In The Red-haired Woman, Cem’s panic when, against his mother’s orders, he is sent down the well is vividly rendered: terror somewhere between claustrophobia and inverted vertigo, compounded by the dread of abandonment.

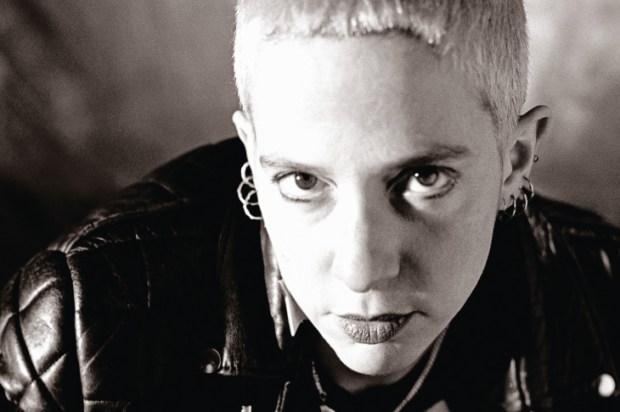

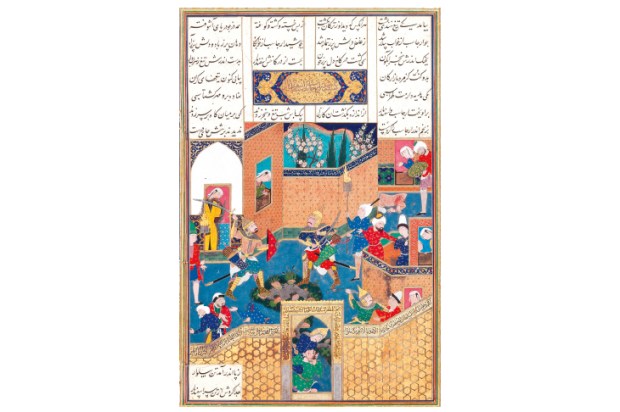

The eponymous red-haired woman is the older woman needed in this impending tragedy. On a trip into the nearest town for supplies, Cem catches a glimpse of her, and is instantly obsessed. She is a travelling player, and her troupe performs scenes — of Sohrab and Rostam, and Abraham and Isaac — with a theme of filicide.

At times, this mythic mix threatens to become heavy-handed. This is particularly true in part two, which traces Cem’s life after the violent episode which ends that all-changing summer. He becomes obsessed by the twinned tales of Oedipus and Sohrab, and points out, unnecessarily, that both share a ‘quest’ for an unknown father, and that ‘when my father left me (as Rostam did Sohrab) … I sought out father figures to replace him and guide me.’ Nice stuff for A-level students, who like their themes signalled loud and clear.

But the final section, which changes narrators and shows the narrative clarity to be illusory, escapes from this expository over-simplification. The themes of parricide and filicide resonate beyond acts of accidental or mindless murder: they explore the loss of connection between generations — which is tragic, yet also necessary. The shifts between generations is beautifully shown through the often hideous changes wrought in Istanbul itself by modernisation. We learn that Cem, reacting against both his father’s idealism and the old-fashioned values of Master Mahmut — rejecting, too, his boyhood dreams of being a writer, which had been fostered by another father-figure, a bookseller — became a property developer. His marriage (excellently drawn) was childless; his company, named ‘Sohrab’, was a surrogate child.

Yet what will the next generation make of his capitalism? The ever-growing suburbs of Istanbul reach out to engulf the town where Cem once spent a hot and mind-altering summer. The fateful well still lies there, hidden; and the elements of another inter-generational tragedy are present.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in