Lord Woolton put it best: ‘Few people have succeeded in obtaining such a public demand for their promotion as the result of the failure of an enterprise.’ By that, the Tory grandee meant that in the spring of 1940 Winston Churchill managed to use Britain’s grotesque military cock-up in Norway, for which he was responsible, to supplant Neville Chamberlain.

Churchill sidelined Chamberlain’s most likely successor, the foreign secretary Lord Halifax. He overcame Tory backbench distrust. He even got Labour on side, though its leaders had long considered him the class enemy incarnate.

What Churchill pulled off, shifting blame for his Norwegian shambles on to his boss in order to replace him, and getting his foes to bend the knee, was a piece of brazen opportunism so virtuosic it would have made Machiavelli blush. Or applaud.

Few Britons today could place Narvik on a map. But, in the spring of 1940, this tiny Norwegian coastal settlement became significant for exporting the iron ore for which the rival British and German war machines were insatiable. For a few days, its name seemed to promise to those gathering around their crystal sets that Hitler would soon reap the Britannic whirlwind. The phoney war was over.

Instead, at Narvik and its environs, Britain got its comeuppance. Our military unreadiness was not entirely due to Chamberlain’s misjudgment in Munich, nor his later misplaced focus on the economic blockade of Germany; but also to Churchill’s fondness for unleashing the dogs of war even when the dogs were toothless and their handlers inept (truths made more unpalatable when one realises that 45 per cent of British public expenditure at the time went on defence).

It was thanks to Churchill’s miscalculations as first lord of the Admiralty that British troops were outmanoeuvred, outfought and out-thought. The Navy placed mines too close to the coast off Narvik to destroy incoming German ships. Troops’ supplies ended up at the bottom of the sea. In one especially shaming battle British troops, lacking air cover, snowshoes, white coats or adequate ammunition, were easily picked off in the snow by fitter, better equipped, often Norwegian-speaking Germans on skis.

It was Churchill who, long after Narvik fell, seemed bent on taking it back, in part, Nicholas Shakespeare suggests, because his nephew, Giles Romilly, a Daily Express war correspondent, had been captured there and shipped off to Colditz.

Worst of all, Churchill myopically fixated on the liberation of Narvik in the hope of eradicating the memory of Gallipoli — the disaster in the Dardanelles in 1916 for which he and his notorious donkey-like commanders were responsible. In that very focus, though, he created the circumstances for an Arctic repeat.

Britain’s first military campaign of the war was such a shambles that reading Shakespeare’s brilliant, meticulous, almost unbearable account of it makes even a jaded Guardianista like me contemplate the middle distance tearfully. ‘Now the veil has been torn aside, revealing the crime of the Norway adventure with all its horror; reckless adventurism, ill-equipped troops sent to their death, colossal military and naval blunders.’ So claimed the leader in the Daily Worker on the morning after George VI invited Churchill to form His Majesty’s new government.

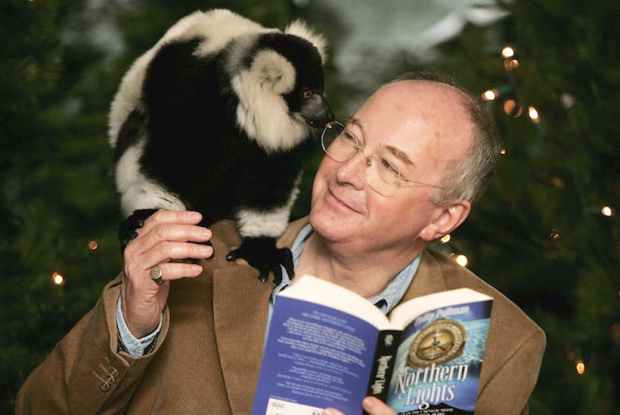

But the Daily Worker was wrong. The veil has not been torn aside. Not until now. The official version of the disastrous Norway campaign and the national soul-search ing in parliamentary debate it provoked has long been Churchill’s memoir The Gathering Storm. There the author gave himself the best lines and traduced his foes. History need not be like that. This scintillating joy of a book — with a military narrative of British shame as well handled as William Dalrymple’s Return of a King, and a treatment of 20th-century British politics, romance, humiliation and desire as grandly realised as Anthony Powell’s great novel sequence — is a corrective, and much more besides.

The author was drawn into this fraught moment of history by his great-uncle, the Liberal MP Sir Geoffrey Shakespeare, who witnessed at close quarters the unfolding events. A friend of the Chamberlains, Geoffrey served under Lloyd George in the 1920s, and in 1937 became first parliamentary secretary to the Admiralty, and so was the official who, on the outbreak of war, introduced Churchill to his new berth.

Shakespeare’s narrative is not just more reliable than Churchill’s, but more fun. With understandable relish he presents us with a cast of dotty poshos and allied eccentrics seemingly strayed from Wodehouse and Waugh. They include Halifax’s mistress, Lady Alexandra ‘Baba’ Metcalfe; her improbably named husband Fruity; Major-General ‘Boots’ Hotblack; not to mention the war cabinet’s answer to Tweedledum and Tweedledee, Samuel Hoare and Leslie Hore-Belisha.

My favourite is Major-General Adrian Carton de Wiart, who lost an eye laying siege to a Dervish citadel and an arm at Ypres. Lighting a cigarette with his remaining arm as German bombs fell from the Norwegian sky and French Chasseurs Alpins dived sensibly for cover, he opined imperturbably: ‘Damned Frogs. One bang and they’re off.’

Even the chief protagonists are beguilingly risible. Churchill couldn’t pronounce his s’s, Halifax had trouble with his r’s and Chamberlain clung tragicomically to his dignity as his career sank. Halifax, above all, intrigues me. He secreted his lover Baba in the Dorchester as assiduously as he concealed his deformed hand in a glove. He hid his own claim to the premiership behind a veil of crazy decorum, citing the English virtues he found in Dryden, who wrote: ‘Anything, though ever so little, which a man speaks of himself — in my opinion is still too much.’

What this meant in May 1940 was that, however much Halifax yearned to become prime minister (and I think he really did), he was temperamentally unable to make the case for himself; rather, he hoped others would do that for him. Unsurprisingly, as Britain needed a rather less passive leader at this difficult moment, they didn’t.

Two vignettes clinch the case for Shakespeare’s superior literary genius over everybody’s favourite bibulous Nobel laureate. He threads the book with references. He tracks the 19-year-old private Frank Lodge being seasick on his way to the Norwegian battle through to his death in 2012, his demand for fallen comrades to be posthumously honoured with Norway Campaign medals unmet. Britain, shamefully, has done its best to airbrush the ordeals of these men.

The other vignette has black-clad Margot Asquith visiting Downing Street to condole with Chamberlain shortly after his resignation. She knew something of what he was feeling, since her late husband was toppled in similar circumstances by Lloyd George in 1916. Shakespeare writes that, in Chamberlain’s kind reception of her, there was something magnificent and humane — qualities certainly lost in history’s cruel verdict on him. Margot saw that Chamberlain had

less self-pity and self-love than any man she knew. ‘I looked at his spare figure and keen eye and could not help comparing it with Winston’s self-indulgent rotundity.

Shakespeare’s eye is at its keenest when he shifts the action from Arctic battlefields to the Commons’ hothouse. There, as his title suggests, six minutes in the division lobbies proved decisive in destroying Chamberlain. The vote was actually 281 to 200 in Chamberlain’s favour, but that margin, when the government majority had been 213, was so feeble as to undermine his credibility.

It’s all here — Quisling catcalls in the lobbies; tearoom recriminations; the Brummie Brutus Leo Amery turning on his fellow second city Tory MP, Chamberlain, during the debate and shouting, ‘For God’s sake go!’ The heartless chorus of MPs yelling ‘Go, go, go!’, Shakespeare poignantly suggests, rhymed with Gielgud’s King Lear who, across the river at the Old Vic, was sobbing ‘Howl, howl, howl’ as he held the dead Cordelia in his arms.

And yet those six minutes need not have been decisive in ousting old King Neville from his power base. Chamberlain could have survived but for two later episodes. First, the telegram from Bournemouth to No. 10 in which Clem Attlee — nicknamed the Clam for his reticence — opened up and expressed Labour’s determination to serve ‘under a new prime minister’.

Then there was what Beaverbrook called ‘the Great Silence that saved Britain’ in the Cabinet Room of No. 10 on the afternoon of 9 May. Memoirs conflict on what happened during the meeting, but Halifax reportedly said little to advance his suit (hoping others would say much). The chief whip, David Margesson, was likewise taciturn; while Churchill had been enjoined by advisers to stay his customary verbosity. Chamberlain perhaps read the resulting silence — which some say lasted longer than the two minutes given to our war dead on Armistice Day — as signalling that he must go. When the four men emerged from the meeting, Chamberlain set off for the Palace to offer his resignation and Halifax contemplated the political abyss (he served later as our man in Washington). Churchill the outsider had become the shoo-in.

It was — in its bumblings, its evasions and, paradoxically, its ruthlessness — a very British coup. And yet a necessary one. Margot Asquith realised after bidding the Chamberlains farewell that sad May evening ‘how much Churchill loved making war, and how he relished being on the bridge of a fighting frigate in the middle of a gale’. She sensed then what we can confirm now with hindsight: that Churchill was, improbably, two Gallipolis and a reckless temperament notwithstanding, the leader Britain needed.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in