An artist ought to draw on broad human sympathies and an intense commitment to his craft. In both respects, Charles Church qualifies. As a youngster, he set off for art school, in search of instruction, and found it: a worthless curriculum. There was no copying of Old Master drawings (no drawing of any kind), no still lifes, no painting from the nude: no attempt to hold the youngsters’ noses to the grindstone of technique. He could have majored in acrylic, self-expression and pretentiousness. He could have qualified himself to be a court painter for Charles Saatchi and a future rival to Gilbert & George. Instead, he spurned meretriciousness and fled to Newmarket.

There he slept on straw, took whatever work was going in stables and restaurants, and spent every hour he could drawing and painting. Commissions followed: Charles found favour — with everyone but himself. He could produce an equine portrait which impressed the horse’s owners. An adequate living beckoned. That was not enough. ‘Als ich kann’ was Van Eyck’s motto. If that was good enough for a sublime master, it was an example which an apprentice should follow.

So Charles set off to study at the finest art school of this era. In Florence, an American called Charles Cecil teaches art properly. He is a perfectionist. I have not met this other Charles, but from what I have heard, he is a fascinating and complex character. In an age when the artistic canon, after more than six centuries of hard-won excellence, is under continuous threat, Charles Cecil plays a similar role to those embattled monasteries off the west coast of Ireland that preserved European civilisation during the Dark Ages. He has been lauded by a third Charles, the Prince of Wales, the most important benign aesthetic influence in modern Britain.

By now, Charles Church had found other exemplars and discipleships: Samuel Peploe, Alfred Munnings, Samuel Johnson and the Belvoir Hunt. He wanted to paint Iona. As Johnson famously observed, ‘That man is little to be envied… whose piety does not grow warmer amid the ruins of Iona.’ Those rebuilt ruins are reinforced by a mystical landscape, which Charles is still trying to capture. The influence of the Scottish colourists is clear. So is the struggle to emulate nature. Confronted by the implacable glory of those waters and mountains, it might seem more natural to fall to one’s knees than to stand at an easel.

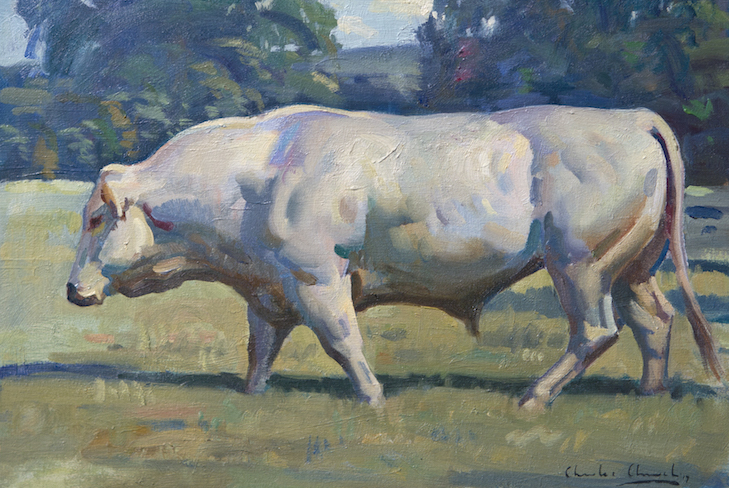

Horses, hounds and huntsmen: it is no insult to deem them lesser deities, easier challenges for oil and canvas. Church is in the footsteps of Munnings, an excellent horse-painter. One of his paintings in the Munnings tradition, a Belvoir huntsman, mounted in the midst of his hounds, tells us everything we need to know about the folly, the evil, of any attempt to ban hunting.

We discussed all these matters over lunch at Franco’s, the Italian restaurant on Jermyn Street. As it is midway between the splendour of White’s and the grandeur of Wiltons (or should that be the other way round?), Franco’s is sometimes underrated. But the food is excellent and the Italian wine list one of the best in London, with thoughtful choices from every Italian wine-making region.

To work through Franco’s list would be a delicious shortcut to expertise. We concentrated on the house of Sesti, from Montalcino. A Rosso ’14 was fine; the Brunello ’08 was in perfect condition. Rosso would work well with a daube of horse that had come to a heroic end in the hunting field. Even though it evokes the gentler hills of Tuscany, the Brunello is fully worthy of game from the Highlands.

Charles has an exhibition opening next week, in Gallery 8, Duke St, St James’s. Round the corner from Franco’s — that is a happy juxtaposition.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in