Andrew Michael Hurley’s debut novel, The Loney, is an unsettling gothic horror story set on a bleak stretch of the English coast. It was first published in October 2014 by Tartarus Press, a tiny independent publisher. It won the Costa First Novel Award in 2015 and went on to be named Debut Fiction Book of the Year and Overall Book of the Year at the British Book Industry Awards. Stephen King called The Loney ‘an amazing piece of fiction’.

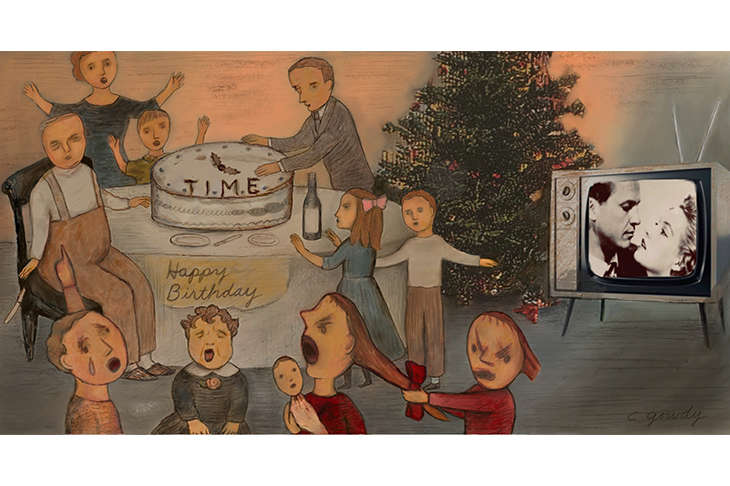

Peace. It had been a rare thing all day. Ian and Jane had come with their other halves and all seven grandchildren, who, after handing over their gifts and cards, had been split by gender.

Imagining the thrill of receiving presents and attention two days on the trot, the boys were envious of Grandad Jim having his birthday on Christmas Eve; while the girls suspected that both celebrations would be inevitably melded into one by thrifty parents.

‘Thick what lies for Portuguese,’ said Ella, though Jim knew that he couldn’t have caught it quite right. Young people always spoke too fast.

‘Again, for Grandad,’ said Jane. ‘Slowly.’

Ella looked at him and exaggerated each word, moving her mouth as if she were chewing a large piece of toffee.

‘I said, think what it was like for poor Jesus.’

On the last word she rocked an imaginary baby in her arms.

She was the youngest of the grandchildren and the others laughed at her as they were called to the table to eat. Ian had brought casserole and his wife, Bernie, had made a birthday cake with 79 piped onto the icing in large silver numerals. None of them had ever made such a fuss on his birthday before — Ian and Bernie had driven a good 200 miles just to have dinner with him, despite their debt — but since Rose had passed away in the summer a pity party like this had not come entirely as a surprise.

‘Mike and I are still happy to have you tomorrow, Dad,’ said Jane from across the table. ‘It’s not too late to change your mind, you know.’

Jim’s son-in-law, still atoning for the fling he’d had with the new girl in the Department back in the summer term, wiped the beer foam off his moustache with his thumb.

‘And the kids would love to have you there,’ he said. ‘Wouldn’t you, gang?’ Four of the grandchildren dutifully nodded.

‘See,’ said Jane.

‘Don’t pester him,’ said Ian. ‘He’s told you he’ll be happier on his own.’

But Jane ignored him and kept her eyes on Jim. ‘It’s no bother for us to come and fetch you in the morning,’ she went on. ‘Or you could even stay with us tonight. I can pack you a bag.’

‘For Christ’s sake, Jane,’ said Ian, laughing. ‘Let the poor bloke do what he wants.’

Bernie agreed.

‘It is up to him,’ she said.

‘I know,’ said Jane. ‘But with Mum gone and everything I just don’t like to think of him sitting here all by himself tomorrow. Why don’t you come to us, Dad?’

Jim shook his head.

‘Well, I will ring you,’ she said, giving him a stern look. ‘After the Queen.’

‘He’ll still be down the Three Hares,’ said Ian. ‘Won’t you, Dad?’

‘You’re not going to the pub, are you?’ said Jane. ‘In this weather?’

When Jim waved his hand at her, she frowned with concern.

‘Well, you’d better be careful coming home afterwards,’ she said. ‘Do you want me to arrange a taxi for you? I’m sure there’ll be a firm somewhere still running tomorrow. There’s that place on the high street by the Co-Op.’

She turned to Ian and mouthed, ‘He’s not listening.’

‘He’s just tired,’ Ian replied. ‘You’re tired, aren’t you, Dad?’

Jim conceded with a brief smile and Ian patted his shoulder and said that they’d leave him be once they’d eaten.

He wasn’t tired at all — at least not in that way — but it would be a foolish man, he thought, who didn’t take advantage of the assumptions folk made about him from time to time.

Peace. It had come a little closer now they’d all gone. Jim poured himself a glass of scotch and switched on the television. Someone was violating a turkey on a cookery show, while two people in Christmas jumpers were drinking wine and laughing. The other channel was broadcasting Carols from King’s, the words to Angels from the Realms of Glory subtitled at the bottom of the screen. He smoked an Embassy and watched the choristers making vowel shapes as they came to the final in excelsis deo. Then it was the Seventh Lesson, in which the heavenly host burst the sky in a flowering of light to terrify the shepherds on the hillside. And as it came to pass, Jim thumbed the remote and found a black and white film where Indians in war paint and feathers were galloping across a prairie, and then an advert for a homeless charity.

Rose would have had her purse open immediately, as she always did whenever anyone rattled a tin at them in town.

She watched him from the mantlepiece, Greek sunlight blanking off her glasses on the first foreign holiday they’d taken as a family. 1972 or 73 or 4, the exact year had slipped his mind, but he remembered painting the lizards that basked on the hot walls; how the children had turned cinnamon-coloured; Rose’s long slim legs, red wine on her lips.

Forty-odd summers later she’d died a gargantuan, gasping woman. Six men under her coffin at the burial. A strange afternoon of handshakes and too much Guinness and a restlessness that still hadn’t settled the following day or the next.

A few weeks after the funeral, Mary Devlin from over the road had invited Jim to one of her Wednesday afternoon sittings. He’d drunk tea with the ladies in the back room and then Mary had closed the curtains and looked into her grubby mirror but no face had appeared in the glass. He’d never caught Rose out of the corner of his eye as he walked about the house. No white feathers ever drifted across his path. He knew that if contact were possible from wherever she’d gone then she would have moved heaven and earth to comfort him. Her silence was proof that there was nothing other than this. If a person endured at all, then it was only in the minds of the people who’d known them, where they were pinned like photographs, hideously unreal.

Often, he wished that he had a memory like Elizabeth two doors down. Rose would drop in to see her every other day and he’d kept her garden tidy until her son took her into a home on the other side of town. The past for her had never consisted of anything longer than a minute and the world still had the capacity to surprise and amuse. Where had this cold cup of tea come from? Why was she wearing yellow? Who was that strange man buttock-up in the buttercups?

She’d been made of air, Elizabeth, content to float wherever her mind took her, whereas he was saturated with the claggy stuff of the past.

Dusk passed into darkness and fresh snow began to fall slantways through the orange of the streetlight on the other side of the road.

He watched the Devlins’ boy, Charlie, scrape what he could from the bonnet of a parked car and clump together a snowball. The two friends who were with him set off running down the road and Charlie flung the missile after them with the dextrous wrist-flick of a fielder at deep mid-wicket.

He ducked the first counterattack and the second missed him by a country mile and shattered into a hedge.

Charlie showed his friends his middle finger and went up the drive to his front door, knocking down the wreath as he struggled with key and handle.

Shaven-headed, his forearms blue with tattoos, he worked at the foundry now and was old enough to come home steaming from the Three Hares on Christmas Eve, but Jim remembered him as a bonny, inquisitive lad of ten who liked to lean on the gate and watch him gardening. He could never make out a single word Charlie was saying, mind you, and one afternoon when he was gabbling away Jim had gone inside and fetched a notepad and pencil.

How cum your deff? Charlie had put as Jim worked manure into the rose bed.

The fork against the wall, Jim wrote: old age.

Charlie thought for a moment and then jotted down his next question.

Wats it like?

Being old?

No, being deff.

Recalling the nights he’d spent comforting Ian or Jane when their foreheads were sweltering and their glands had swollen to the size of plums, Jim wrote: think of when you’ve got a cold and everything’s muffled. It wasn’t quite like that — he couldn’t hear a single thing these days — but it was as close a description as he could give that Charlie would understand.

Charlie nodded and then as Jim went to prune the winter jasmine he followed him scribbling feverishly on the pad.

Why dont you have a nearing aid?

How do you think if you cant ear owt?

Can you remember wat voyces sound like? Can you wissle?

He’d reminded him of how Ian and Jane were at the same age. Not afraid to speak their minds. Not afraid of anything. When arrears and infidelity were as alien to them as discretion.

Across the road he was still confounded by the door and finally Mary Devlin opened it and hauled him inside.

A car slowly parted the ice and slush, as cautious of slipping as a tightrope walker. Someone in a sheepskin coat waited while their dog stained the pavement before moving on. And then the street was empty for a while until a group in black coats began to gather by the lamppost, some with small leather books, two with brass instruments. They arranged themselves with professional quickness, the trombonist and trumpeter standing side by side on the kerb. The conductor — a diminutive man in a flat cap — held his forefingers very still and then slowly buttered the air with his hands as he brought the choir in on something gentle: ‘Once in Royal David’s City’, perhaps, or ‘Silent Night’.

The Devlins — all seven of them, including Charlie — massed at their front window to watch. In due course, others from the street emerged from their houses, wrapped up in hats and scarves and their thickest coats.

The choir got through four or perhaps five carols, it was hard to tell exactly, and then the conductor removed his cap and passed it around for donations. Once everyone had contributed, the singers put away their books and the players packed up their instruments and Jim reckoned they’d be heading for the Three Hares next to milk the guilty drunks who should have been at home wrapping presents or reading their children Christmas stories.

But before the choir moved on, the little red-haired girl who’d stood at the front and been so attentive to the conductor’s lilting hands pointed to Jim and one by one the rest shifted around to look at him. For a moment it seemed as though they were about to come over and he was glad when a van turned down the street and prevented them from crossing. The main light off, he pulled the cord which drew the curtains. When he fingered open a gap a minute later everyone had gone and the street had been abandoned to the squally quiet of the snow.

He felt Rose looking at him and guilt put another inch of scotch in his glass. Time was, she’d have had him up off his chair and outside on the street, joining in with the carollers. Even before he’d lost his hearing he’d been tone deaf, but Rose had been blessed with a honeyed voice and there had been no greater pleasure than to listen to her singing as she played the piano in the hallway.

The music used to rise like warm air up to his studio as he worked. The door was always open. He pictured Ian coming in and sitting cross-legged on the window seat to look at the books of Dürer’s etchings or Goya’s grisly paintings. Now Jane followed and climbed onto Jim’s lap and wanted him to draw monsters. And then all three of them were kneeling on the floor sketching an imaginary landscape onto a long offcut of wallpaper; something like an old Japanese scroll map; theirs a formidable, mysterious prefecture of snow-thatched mountains and twisting rivers through which they contrived an odyssey for their hero, while downstairs Rose sang ‘These Foolish Things’.

It wasn’t just nostalgia. Fuck nostalgia. Certain times had existed in exactly that way, when everything good in his life had tessellated for a moment before fragmenting again.

Getting older, he felt more and more like a passenger trapped on a fast-moving train, with no choice about destination or what fell behind. His parents, his little brother, Eamon, Rose and her songs — they were all gone; so too the Ian who dreamed of the Colossus, the Jane who coloured in the beasts that he invented for her, the Charlie Devlin who pestered him around the garden, blissfully confused Elizabeth at number 21. The grandchildren were growing up too. Ella was in the juniors now. Joe was applying for university.

It was all completely natural, of course; time’s endless freefall had been set in motion long ago, but forced by his age to remember and remember and remember, Jim felt that he was always swimming against the flow and he was exhausted.

After a third glass and another half-smoked cigarette, he slept without meaning to and woke just before midnight, his mouth furry and his stomach tart with indigestion. With the living room dressed up for Christmas by the children, it looked unfamiliar and it took a moment for him to determine where he was. Holly grew from the picture frames; the hearth was pasture for a herd of wooden reindeer, the lights on the tree jazzed behind the tiny stained-glass windows Ella had hung on the branches.

He flicked off the switch, made sure the fire was out and went into the hallway to the foot of the stairs.

It was time.

And he was strangely unafraid.

Peace. It would come quickly and be of the purest kind.

There was nothing left to worry about.

Everything was in order.

The letters he’d sent that morning would probably reach Ian and Jane after Boxing Day, although knowing what the post was like at this time of year it might even get to New Year’s Eve before they found out.

It would be a shock for them, of course, nothing he could have written would have prevented that, but his reasons were clear, like his declarations of love were clear, and the instructions for how they should deal with things afterwards. All the bank statements and deeds, the funeral plan and his will would be on the kitchen table. And Ian should go up to the bathroom alone.

It felt right to do it there. He didn’t want to cause any more work than was necessary, not at Christmas. Ian would only need to pull out the plug and the water would drain away.

As soon as everyone had left after lunch, Jim had done the mortice but habit made him double check that the front door was locked. Through the pleated glass, he could see shadows raking across the white of his driveway. Sometimes teenagers would sit on his wall and smoke but it was far too cold for them to linger tonight. It was the carol singers from earlier, he assumed, grouping around the streetlight on his side of the road. Perhaps their tactic was to reverse their route and double the funds for the church roof or the organ bellows or whatever they were collecting for. But although some folk along the street were probably still awake and no one would begrudge hearing a little more singing on Christmas Eve, it seemed oddly late.

The shadows moved again, seeping towards the house, until he could make out more solid shapes on the other side of the door. The light wired up to his bell glowed and faded and then someone was trying to look in, shielding their eyes, the skin of their hand pressed whitely against the glass. The light flared again in two short bursts and, keeping the chain on, Jim turned the key.

The choir was assembled in a line that stretched down the path to the gate. The dwarfish conductor gave a little bow and behind him the rest of the singers looked in eagerly. Jim dug into his pockets and found a couple of pound coins and some coppers that he pressed into the conductor’s open hand before he realised that the man had not been gesturing for money but asking if he and the others could come inside. It was colder than it had been earlier. The snow had stopped falling and the newly cleared night had hardened the air.

Beside the conductor stood the little red-haired girl, with her hands jammed under her armpits and her chin burrowed into her scarf.

Thinking of Rose, Jim undid the chain and let them in and the full dozen or so crowded into the hallway, their coats damp and earthy, the coldness they’d acquired from a night out wassailing the estate damping down the last embers of warmth in the house.

The trombonist sat on the stairs and ran his fingers along the green tinsel that Jim had taped to the banister. The other brass player crouched down to look at the crib and rotated one of the wise men so that he was facing the Saviour. The singers were talking to him from all sides, thanking him perhaps, but Jim struggled to make out what they were saying, not least because as soon as he was beginning to read one person’s lips, someone else would touch him on the shoulder and make him turn. They never quite looked at him, though, and it seemed to him in the dim light that they had no colour in their eyes. Not one of them smiled either, not even the little girl with the red hair who had perched on the piano stool repeating the same unintelligible words. Before a tall, bearded man distracted him with a tap on the elbow, Jim saw that what teeth she had in her mouth were black and wondered if the choir took the poor with them on their circuit of the neighbourhood in order to see that they were fed. Touching the conductor’s sleeve, Jim did a mime of eating and drinking and pointed to the kitchen. There were mince pies left over from dinner, and Ian had bought him a bottle of good brandy.

But the conductor reached between the spindles of the banister to wake the trombonist, who had fallen asleep against the wall. He blinked and rolled his lips before fitting them into the mouthpiece.

Jim shook his head and waved his hand. The neighbours would be asleep by now and in any case repaying his hospitality with a song was a waste.

Not noticing Jim’s appeals, the conductor signalled to the trumpet player by the door and then the singers began opening and closing their mouths in something that seemed so fast and raucous that it would wake the whole street.

Jim could do nothing but wait until the song was over and then he’d smile and shake their hands and show them the door. Politeness would be his last gesture.

But the circle closed around him and he began to hear something growing inside his head. A kernel of sound that built quickly into something like the screaming of apes or an aviary of a thousand different birds. Instinctively, in a movement he hadn’t made for years, he put his hands over his ears to try and blot out the cacophony.

His balance was suddenly distorted and the hallway fell sideways, making the wall the ceiling and the stairs appear to descend away from his feet into darkness. He felt his cheek hit hard against the paisley runner and he lay there with his hands pressed to his head, looking at the faces of the singers, their mouths hanging as slack as those of corpses.

His parents had long since become indistinguishable from the earth in the graveyard of the Galway church where they’d married, and little Eamon — butted by a car as he cycled home from school the day before the war ended — his shattered bones would surely be as soft as cake by now. Yet here they all were among the singers. And Rose too, her skin like wet clay, swelling the old coat she used to wear.

She wailed the loudest of all, insisting that he heard and took notice: life was hard and it hurt, but death — long, choiceless death — was crueller than anything he could imagine.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in