At the launch of the Christmas radio schedules last week, James Purnell, director of radio (and much more) at the BBC, stressed repeatedly the need for radio to be ‘reinvented’ for this new digital age. But what did he mean by reinvent? Was he hinting at the need for a new, leaner radio, the sound-only stations running up cheaper bills for the corporation? Or was he envisaging a translation of the existing radio networks into something more than just audio, focusing not so much on what goes on in the studio but on the new digital future, visualised and captured online.

‘Enhanced’ would have been a much less troubling word to use, or maybe ‘adapted’, taking maximum advantage of what the digital revolution can add to an ‘old’ technology, amplifying what it already does, taking it to a new audience and drawing them in. For what is there that needs to be reinvented about the mystical bond between loudspeaker and listener, that unseen yet profound connection, which is the essence of radio, its unique selling point (to borrow a phrase from marketing), the reason why we stay tuned in.

On Sunday, Radio 3 demonstrated not just its ability to create an invisible yet very real connection between its community of listeners (both at home and abroad) but also how it’s possible to make the best use of digital while retaining the values developed under the analogue regime. Building on the success of last year’s 12-hour sequence celebrating the station’s 70th birthday, Sacred River created a continuous stream of music throughout the day without any presentation or contextualisation. Listeners had to allow themselves to be swept along by its momentum, or as Edward Blakeman, head of music programming at Radio 3, told me: ‘You’ve got to get in the river and you’ve got to float.’ All responsibility was invested in the listener and in their willingness to go along with the flow.

Even 20 years ago such freedom and apparent lack of control would have been anathema to the corporation. Listeners, too, would have been appalled by the absence of direction, the neglect of their best interests. No one telling us what was being played, leaving us to make wild guesses as to what it might be; the odd and unsettling juxtapositions of genre and tone; the absence of any human interaction, no Rob or Sarah or Sean talking us through the music and the day. But of course with digital none of that matters. All we had to do was go online and follow the programme notes that appeared on the Radio 3 website, unfolding throughout the day in line with the music; or brave the tweeting community and join in the virtual discussion about what was being played (a needless distraction for some and yet even I must acknowledge an effective way of building community). And the programme, whole and entire, is up there for 30 days, ready to download via iPlayer at the touch of a button.

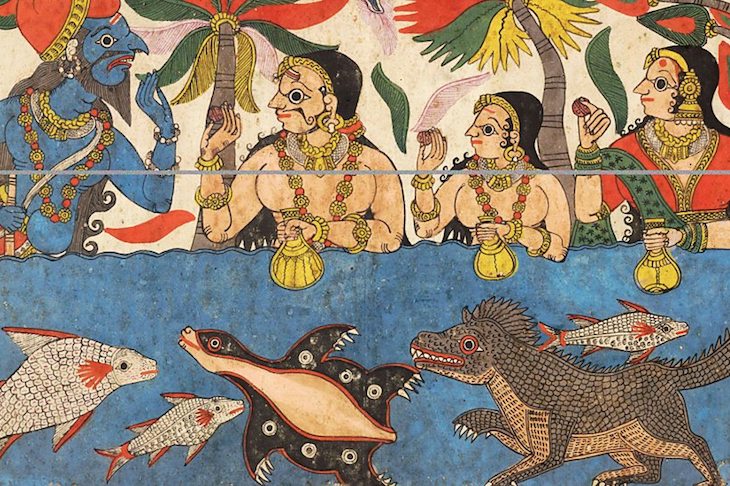

This time there was a structured musical narrative, inspired by and complementing Radio 4’s Living with the Gods series, which under Neil MacGregor’s expert guidance has been looking at the ways in which societies across the world have developed rituals and beliefs that attempt to explain and make sense of our place in the universe. Sunday’s sequence reflected on the ways in which faith has influenced and moulded much of western music, and how music in turn has been used to illuminate and interpret the nebulous nature of belief. Six sections were each introduced by a particular piece of music derived from one of the major world faiths, opening the door on creation, light, nature, love, liturgy and contemplation, and finally life, death and eternity. Nature, for instance, was heralded by a Syrian Orthodox hymn from Antioch, setting the words, ‘A young dove is holding an ancient eagle…’. Liturgy and contemplation began with Buddhist chanting accompanied by the gentle flapping sound of a Buddhist prayer wheel turning in the wind.

The music, curated by the BBC’s religious affairs and music departments in Salford, ranged widely from Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony to Roxanna Panufnik’s setting of the Catholic Mass, via Bach, Bruch, Haydn, Holst, Tavener, Jeanne Demessieux and Tarik O’Regan. The Tavener, though, was not as you might expect inspired by the Greek Orthodox liturgy but by Buddhism, while the chosen piece by Holst was his choral settings of the Rig Veda. Not all the works were choral and word-based. The Bruch piece was inspired by the Jewish prayer recited during the evening service, Kol Nidrei, but a solo cello imitates the sound of the cantor’s voice, leaving the listener free to contemplate the message contained in the music.

The success or failure of such a sound adventure depends not just on the selection and juxtaposition. These pieces were all played live, the producer and studio team lining up each piece of music, one after the other. They decided on the day, in the moment, how long a pause to leave between one piece ending and the next beginning. And it’s in those pauses that the magic happened. The impact of carefully curated silence.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in