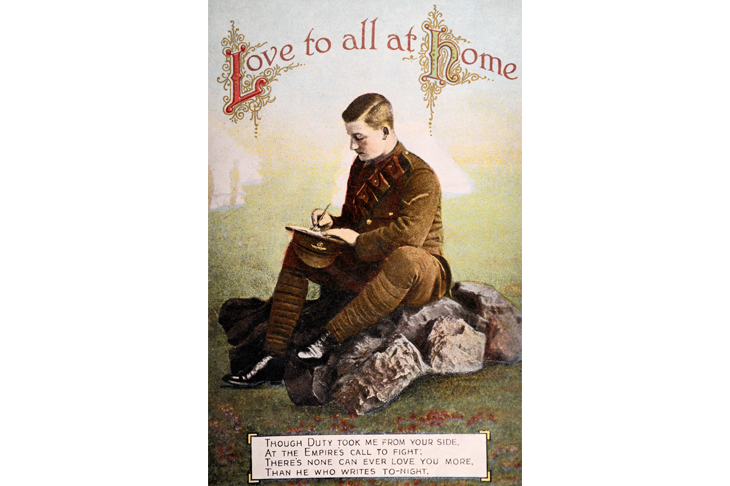

At the close of the 1970s, I found a selection of postcards in an antique shop which had been sent from the Western Front in 1917 by a soldier named Private Howe to his young daughter Ena. I was struck by the immediacy of the language, and the careful avoidance of anything hinting at danger, combined with the tastefully chosen French photomontages of flowers and romanticised battlefields.

In Words and the First World War, Julian Walker has examined many such postcards, alongside letters sent to and from the Fro nt, private diaries, trench publications such as the Wipers Times, national and regional newspapers and other sources. An illustrated analytical study, it considers the situation at home, at war, and under categories such as race, gender and class to give a many-sided picture of language used during the conflict.

This is familiar territory for the author, who co-wrote the book Trench Talk: Words of the First World War, and revisits theoccasional entertaining example from the latter, like the mocking Allied response to the German motto, ‘Gott Mit Uns’ (God be with us), which took the form of a home-made sign reading: ‘Don’t swank! We’ve got mittens too!’

Walker deftly highlights the many communication problems arising during the conflict, for instance in the French army, where there were ‘soldiers from mainland France whose first language was Breton, Flemish, Gallo or Occitan; in the case of Breton-speaking soldiers, for many Breton was their only language’. Some in the war zones attempted to master at least a few foreign words. Local civilians picked up English in order to sell things to troops (including boys offering the favours of their elder sisters); and Aubrey Herbert (the grand-father of Auberon Waugh) recorded meeting a Serbian at Gallipoli ‘who had been learning Italian specifically to aid his ambition of stabbing a Cretan’.

Of course, much of what was said in the military could not be repeated in messages sent back to loved ones, but some tried, as Walker notes:

Capt. R. McDonald censoring his men’s letters read one which said ‘Dear Jeannie, I am expecting leave soon. Take a good look at the floor. You’ll see nothing but the ceiling when I get home.’

Slang, of course, played a significant role, and the greatest 20th-century authority in the field was Eric Partridge, himself a survivor of the trenches. With fellow veteran John Brophy he co-wrote and published Songs and Slang of the British Soldier (1930), the shadow of which has fallen over every work on the subject since. Understandably, Walker references Partridge many times, but the latter might have taken issue with some of the etymology here. For example, Walker speculates that when a soldier with a pistol threatens to ‘let the daylight into’ some prisoners this might be an original coinage, calling this ‘very creative’ — but it dates back to the 18th century. Similarly, when listing sea terms used in a letter from a sailor, he remarks, ‘curiously this glossary does contain the word matloes, from the French,’ as if it was odd to find an ordinary seaman with no language skills using the expression. How-ever, this has been a Royal Navy slang name for sailors from before the Crimean War, and remains current today.

Published by an academic imprint, the book occasionally seems to be using the battlefields of Flanders to fight the 21st-century PC wars over terms for race, identity and sexuality, and retrospectively judge words and behaviour through that prism. These are frames of reference which would have left the lice-ridden, soaking wet frontline troops themselves utterly mystified. ‘In a male-monopolised environment of killing,’ Walker writes, ‘we see the war dismantling the language of stable gender patterns,’ before quoting the example of a man arrested in drag in Highgate trying to rent a room. ‘The details of [his] clothing stand out as the “real story”,’ says Walker. But is this a case of taboo-busting cross-dressing or just a sensible disguise to avoid being sent to the slaughter overseas?

Words were undoubtedly powerful things during the conflict, yet many survivors never spoke of their experiences once peace came. My great-grandfather volunteered in 1914 and finally returned home unannounced in 1919, after being mustard gassed, then listed ‘missing, presumed dead’. He offered virtually no explanation to his wife and family about what had happened or where he had been during the long period when they had given him up as lost, but quietly resumed his everyday life in their Berkshire village. For the rest of his life, though, he refused to countenance a gas cooker or gas heating in his home; that particular word conjured up only one thing in his mind.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in