It has become fashionable since the fall of the Soviet Union to diagnose communist fellow travelling as a form of Freudian neurosis. Where class resentment exists it is said to emanate less from angry young proletarians than from well-spoken youths intent on garrotting their dividend-drawing fathers.

Most contemporary accounts of the Cambridge spy ring, which passed top secret information to the Soviet Union during the Cold War, draw heavily on this cliché. Kim Philby, Donald Maclean, Guy Burgess, Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross are typically portrayed not only as highly privileged men who rebelled against their upbringings, but as an upper-class clique who got away with what they did because they were sheltered under the protective wing of the establishment.

The establishment in this story is presented as an ever-present and incestuous web of prep schools, old-school-tie bureaucracies and smoke-filled Soho clubs. As a representative article in the Guardian put it in 2016, Philby, Britain’s most notorious Cold War traitor, was able to filch secrets for Moscow because British Intelligence was ‘staffed by ill-disciplined and inept upper-class twits’ — twits who were prepared to turn a blind eye to the misdemeanours of one of their own.

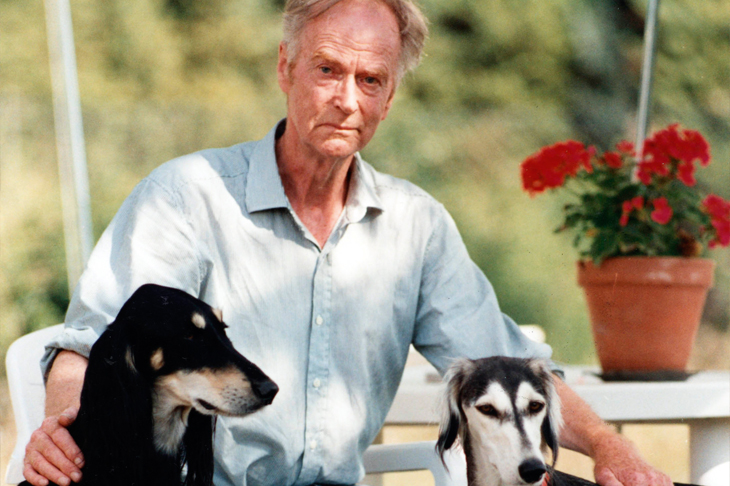

Richard Davenport-Hines gives this narrative short shrift. In a revisionist account of the Cambridge spy ring and its damaging aftermath, he argues that our obsession with the class backgrounds of the spies not only misleads, but feeds into a wider attack on British institutions by populist hot-air merchants. The Cambridge spies ‘did their greatest harm to Britain not during their clandestine espionage between 1934 and 1951’, Davenport-Hines writes, ‘but in their insidious propaganda victories over British government departments after 1951’.

It is the author’s contention that we have come to explain the penetration of the British security apparatus by Soviet agents by, ironically, resorting to Soviet-style class analysis. The Soviet Union has thus won a sort of victory in defeat. The Cambridge spies have come to be treated as a product not of communist subversion, but of British capitalism and the cast of Bertie Wooster-type figures who in the mid-20th century were assumed to administer it.

In reality, none of the Cambridge spies were from Britain’s true upper class; the purported establishment ‘cover up’ was no more than operational procedure within the intelligence apparatus (it is better to ‘mine’ an unmasked spy for information on his employers rather than ‘reveal’ him to gratify the tabloids); and masculine solidarity played a far more significant role in the cultivation of the Cambridge spies than class.

And yet once the Cambridge spy ring had finally been exposed, the myth of an establishment cover-up took root. It has subsequently served to undermine faith in institutions and the bonds of mutual trust which are essential in any democracy. In addition, today’s relentless elevation of opinion over hard-won expertise and knowledge has its antecedents in the exposure of the Cambridge Five. ‘The use of the words “elite” and “establishment” as derogatory epithets transformed the social and political temper of Britain,’ Davenport-Hines writes persuasively. Put another way, the anti-establishment style — along with its mania for toppling esteemed figures —originated in the defection of Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean aboard a boat to Moscow via Saint-Malo in 1951.

Were this argument pursued by a lesser writer, the link to contemporary debates about the rise of populism would feel a little too neat and tidy. There are after all a glut of books purporting to explain Brexit, the rise of Donald Trump and ‘post-truth’ politics more generally. Davenport-Hines’s conclusion — that populism’s attack on informed judgment is a product of the defections of 1951 — slots nicely into this genre. It contains a contemporary ‘hook’ in a way that a straightforward book about the Cambridge spies would not.

But the author’s closing argument — that Michael Gove was ‘parroting attitudes that had first arisen… after the defections of 1951’ when he claimed in 2016 that the British people had ‘had enough of experts’ — is less tricksy than the more conventional attempt to use the men who spied for Stalin to impugn the British establishment in its entirety. This assault on British institutions has long been led by bloviating chancers and over-excitable novelists such as John le Carré. In an essay on Philby published in 1968, le Carré described MI6 as ‘the microcosm of that “great capitalist class” now in the process of internal disintegration’.

The attribution of blame for the Cambridge spies to ‘upper class twits’ has also very often come with a side-helping of unpleasant homophobic innuendo. The ‘wretched, squalid truth about Burgess and Maclean’, boomed the front page of a 1955 edition of the Sunday Pictorial, ‘is that they are sex perverts’.

Enemies Within provides a comprehensive demolition of many widely accepted myths surrounding communist subterfuge during the Cold War. The author is perhaps too dismissive of the power of class loyalty at times, and does not (to my mind) draw enough of a link between the capitalist populism of the 1980s and the contemporary celebration of ignorance and what he calls the ‘mass appetite for discrediting highbrows’.

It is also hard to lament the passing of a culture of unquestioning faith in institutions and tradition, which was also at times a culture of silence and cover-up, as was demonstrated by the BBC during Jimmy Savile’s time at the corporation.

Nevertheless, when every dreary mediocrity is nowadays rallying with thinly disguised ambition against a nebulous ‘establishment’, it is encouraging to come across such an erudite and unapologetically ‘elitist’ counterblast.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in