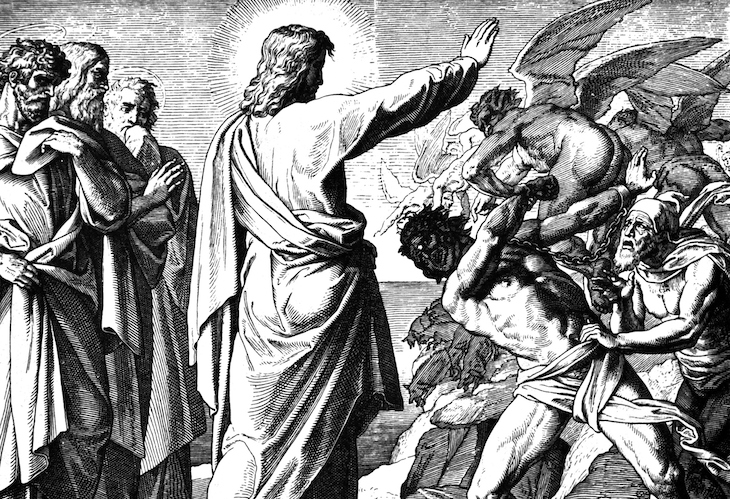

As well as writing about religion, I have always been an amateur religious artist. Recently I’ve been getting a bit more serious about it, and have made a few art works for churches. I recently created one for a City of London church. The vicar, a friend, suggested it might appeal to youngish people somewhat at odds with conventional church (his church hosts such a group). I made a large fabric collage depicting an exorcism: Jesus casting out a demon. I said a few words at its unveiling, which seemed to go well.

But not everyone was happy. A few weeks later the vicar told me that the picture had been taken down, following a complaint. Well, my slapdash neo-primitive style is not for everyone, I conceded, a bit baffled. No, he said, this person felt very uncomfortable due to the anti-LGBT associations of exorcism. She thought that this was a community in which she could feel safe — and she had brought her girlfriend to a service hoping to show her how welcoming it was —and instead this slap in the face: an art work that seemingly celebrates the toxic practice of ‘deliverance’ used by anti-gay fundamentalists. The experience had so shaken and shocked her that she was losing sleep, she told someone else at the church, who passed on the information to the vicar.

I was expecting a few hurdles in my new side career of religious artist. But this was unexpected: to be accused of persecuting homosexuals, on account of having attempted to depict the theme of exorcism. Isn’t exorcism in the Bible, I asked the vicar? Would she like Jesus’s exorcisms to be snipped from the gospels? He agreed that her complaint was theologically shaky, but said that we are living in a rising climate of sensitivity, including in the churches.

I shouldn’t have been too surprised. I encountered similar sensitivity in a previous attempt at a side career a few years ago: teaching Religious Education at a private school. The textbook contained Michelangelo’s famous image of God creating Adam. I made a jokey reference to the childlike littleness of Adam’s genitalia, despite his muscle-man physique. Big mistake. One of these 11- or 12-year-olds reported the comment to a parent who reported it to the head who hauled me in for a surreal conversation about the mentionability of Edenic pudenda. I bet science teachers are allowed to mention penises, I protested — why shouldn’t humanities teachers, especially if the penis is actually depicted in the approved textbook?

So are holy snowflakes smothering the C of E? I consulted the vicar of a north London church who had worked at a cathedral, where his role included commissioning works of art. ‘What I’ve noticed is that sensitivity has become more secular than religious — it used to be that people were nervous of doing or saying something sacrilegious; now they’re more likely to worry about giving secular offence. And often they are not really offended themselves but are imagining other people’s reactions; they are upset on others’ behalf. So I sometimes have to persuade parishioners that something is not as problematic as they fear.’

A vicar of a central London parish told me that some of her parishioners are excessively worried that traditional Christian themes might seem illiberal. ‘We were planning a series of Lent talks last year, and brainstorming for a theme. I thought “sin” would be pretty uncontroversial, but the most vocal members of the group were dead set against it. That’s the image of religion we want to get away from, they said; it sounds so judgmental.’ But faith is controversial. There’s no getting away from it, and that’s no bad thing. Anything worthwhile is and should be challenging.

Consider Christian art’s most famous images. Adam and Eve is troubling on three grounds: their nakedness, which is simultaneously innocent and (in our fallen eyes) not; their stubborn heterosexuality; and Eve’s alleged culpability for the human disaster. Then there’s the Passion, with the crucifixion and related events. All that glorying in pain. The same applies to depictions of martyrs. Finally, images of victory: Christ or one of his stand-ins crushes Satan underfoot or lances a dragon or raises a victory banner (which bears an unfortunate resemblance to the England flag). We have already seen the umbrage people take when you persecute demons.

Instead of tiptoeing away from their tradition, Christians should embrace it. Neither faith nor creativity is compatible with running scared. The church should be a refuge but it can’t be a safe space.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in