In 1971 the late Linda Nochlin burst onto the public scene with her groundbreaking essay, ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ Unlike other apologists, she made no claim that there were, in fact, great overlooked women artists but shifted the ground of the question to ask why circumstances made it impossible for women to be great artists.

If it might seem an obvious question now, that is in part because she made it so, and almost 50 years later she has brought the same clear-eyed approach to the representation of misère in 19th-century art. In one sense, of course, what she is writing about is economic poverty, but the misère of her title carries with it the more profound and degrading connotations that the French sociologist Eugène Buret identified in his 1840 De la misère des classes laborieuses en Angleterre et en France: ‘the destitution, the suffering and humiliation that result from forced deprivation’; poverty ‘felt morally’, afflicting ‘the whole man, soul and body alike’.

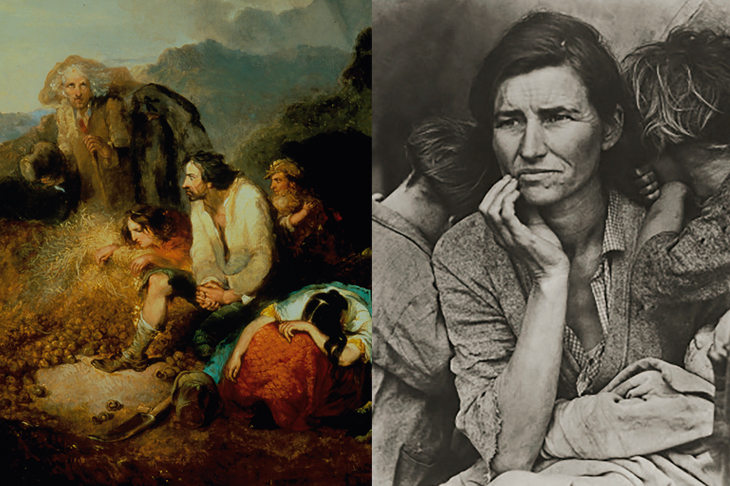

Rooted firmly in Buret’s notion of misère, Nochlin’s book is essentially a collection of five case studies that enable her to explore the ways in which artists responded, and still respond, to the phenomenon. For all its occasional academic language, there is nothing abstruse in her method or her concerns. In ‘The Irish Paradigm’, for instance, she addresses the ethics of the depiction of human suffering, the self-imposed limits that prevented artists conveying the full horror of the situation to the general public, the art historical pedigree of the recurring imagery of mother and child and, conversely, the lack of precedence for the depiction of mother and dead baby.

She analyses the merits of illustrations of misère in both the graphic arts and photography and contrasts these with the amateur sketch or the unaesthetic snapshot which arguably gives a more immediate and authentic account and goes on to discuss the value of the documentary image once it has become a cliché. Finally, she considers late 20th-century Irish famine memorials in Sydney, Boston and New York. In the latter’s Battery Park an entire smallholding, including walls, grass and a real abandoned Irish fieldstone cottage, seems to have been tipped into a high-rise city setting.

Just as in her seminal essay on women artists, here too Nochlin shifts our perspective and grounds of enquiry. She cites images of prostitutes — at work, asleep, waiting for a medical inspection — in works by Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec and others and asks where, in an age and milieu in which syphilis was all but endemic and its symptoms were often the subject of caricature and popular art, are the high art images dealing with the indignities suffered by men? The answer, inevitably, is that the works we know are all the product of male artists. The female view is so rarely heard that when Nochlin quotes Flora Tristan, a French social theorist, writing in 1840 about the degradation of prostitutes in London, it is intensely shocking. ‘Oh,’ she writes, ‘if I had not witnessed such an infamous profanation of a human being, I would not have believed it possible.’

Nochlin is characteristically good at choosing and discussing her cases. Géricault’s deeply compassionate series of London lithographs contrasts with Goya’s de haut en bas drawings of beggars. Courbet, the subject of Nochlin’s doctoral thesis, unsurprisingly is well represented, while the last case study features the little known but powerful paintings of Fernand Pelez (1843–1913) wonderfully dubbed the ‘Master of Miserable Old Men’. Nochlin describes his style as ‘a blend of detailed realism and emotional distance’ and the works reproduced are both affecting and disturbing. At over 6 metres wide his ‘Grimaces and Misery: the Saltimbanques of 1888’ is a tour de force of exhausted, bored, disillusioned performers. The now lost canvas ‘A Morsel of Bread’, a multi-panelled grisaille commissioned by the French state and completed in 1908, depicts a row of old men in a breadline that seems, in pathos, humanity and composition, to prefigure Sargent’s ‘Gassed’ of some ten years later.

‘I have lain awake for hours,’ wrote the American philanthropist Elihu Burritt, frustrated at the inadequacy of language to do justice to the tragedy of the Irish famine, ‘struggling mentally for some graphic and truthful similes, or new elements of description, by which I might convey to the distant reader’s mind some tangible image of this object.’ It is to Linda Nochlin’s credit that she has found the words to match the images that form the heart of this beautifully produced book. Don’t be put off by the title.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in