I have occasionally mused that there is plenty of scope for a Tate East Anglia — a pendant on the other side of the country to Tate St Ives. If ever that fantasy came to pass, the collection would include — in addition to Grayson Perry, Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious, and John Wonnacott, contemporary master of the Thames Estuary — a section on Sir Cedric Lockwood Morris.

The more one delves into the history of modern art in Britain — indeed, into art history in general — the more one discovers that many reputations are still free-floating. Morris’s is certainly one of these: there is no consensus as to how good he was as a painter, nor as to how he fits into the wider story. Currently, three small-scale exhibitions — at the Garden Museum, Philip Mould & Company and Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury — help answer those questions. Even taken together they don’t add up to a full retrospective, but they do give quite a few clues.

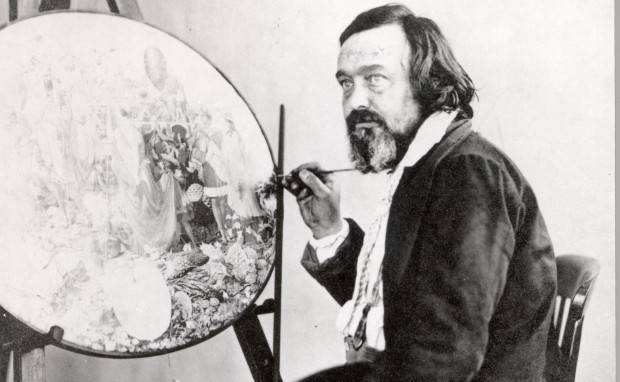

For the second half of his long life, Morris (1889–1982), though a Welsh baronet in origin, was based in southern Suffolk and northern Essex. There, from 1937, he ran a private and highly unorthodox institution with his partner, Arthur Lett-Haines: the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing. After its premises in Dedham were burnt down in 1939 — possibly as a result of the star student, Lucian Freud, leaving a smouldering cigarette on his easel — this was relocated to Morris and Lett-Haines’s rustic dwelling, Benton End Farm near Hadleigh.

Despite the name, it would be misleading to describe theirs as a typically East Anglian ménage, except architecturally. Rather, it was an outpost of post-impressionist France, with its sexual unconventionality and aesthetic fastidiousness, transported into Constable country. The writer Ronald Blythe recalled the atmosphere as having ‘a whiff of wine and garlic’.

According to Blythe, the spirit of the household was ‘robust and coarse, and exquisite and tentative all at once’ — and also, he added, ‘faintly dangerous’. The visitor encountered a cast of characters including ‘knowing’ youths and ‘formidable women fatiguing the salad’ (one of the latter being Kathleen Hale, author of the series of children’s books about Orlando the Marmalade Cat). The doors and window frames of the ancient structure were painted glaring blue; inside there was a ‘cool ochre room crammed with lustre and bold oils of sea birds’.

‘Pin Mill and Black-Headed Gulls’ (1929), displayed at Philip Mould, must be the very picture Blythe was thinking of, the gulls of the title being bright-eyed, slightly vicious-looking creatures. ‘The Orange Chair’ (1944), on view at the Garden Museum, shows a corner of the interior at Benton End. But with the simple furniture and still life of fruit, vegetables and potted plant, this could almost be Van Gogh’s kitchen in Arles.

There’s a clue to Morris’s source of inspiration. Before settling near the Stour valley, he and Lett-Haines had spent formative years in bohemian Paris. They then transported many of the attitudes and interests of the French avant-garde of the late 19th and early 20th centuries to rural England. The food cooked by Lett-Haines in that kitchen was much like that served up by Toulouse-Lautrec (a noted amateur chef), or eaten in Monet’s dining room at Giverny: what Elizabeth David, a habitué of Benton End, popularised as ‘French country cooking’.

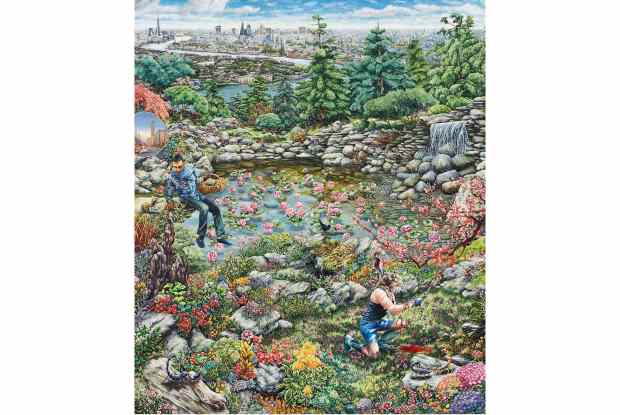

Morris’s domain was outside. He wasa celebrated gardener and noted breeder of irises. In this too there was a French connection. The garden at Benton End, informal in arrangement and with an emphasis on colour, brings Monet’s gardens to mind. The celebrated garden designer and plant breeder Beth Chatto was another friend (her memoir of Morris, ‘artist-gardener’, is reprinted in the Garden Museum catalogue).

But what of Morris the artist? In that respect Lucian Freud’s telegraphic judgment, quoted by William Feaver, can’t be bettered. Morris, Freud believed, was ‘a real painter. Dense and extraordinary. Terrific limitations’. Both aspects, positive and negative, are on display in these mini-exhibitions. On this showing, he was at his best when painting food and flowers, which makes the Garden Museum show the one to go for if you have to choose. He conveyed the individuality of each bloom, but also a slightly menacing quality — that ‘faintly dangerous’ air Blythe mentions, which is just off surreal. His thick impasto and directional brush strokes, following the form of each leaf and petal, suggest that Van Gogh — another master at depicting irises — was his reference point.

On the whole, Morris’s landscapes carry less of a charge, while the portraits havea hint of caricature, which Freud noted and found attractive — although ultimately this is indeed a limitation. You get the feeling that Morris was more fond of flowers and vegetables than people. But that, after all, is a comprehensible — and probably widespread — point of view.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in