It’s been a good couple of weeks for cuddly toys in opera. A big floppy Eeyore is the only comfort for 11-year-old Coraline at the darkest moment of Mark-Anthony Turnage and Rory Mullarkey’s new opera. The teenage Composer in Antony McDonald’s production of Ariadne auf Naxos has a Beanie Baby panda as a sort of mascot: a tiny, limp emotional defence against a world that’s about to spin deliriously off kilter. Hansel and Gretel don’t have any toys, but the brattish siblings of Stephen Medcalf’s staging at the Royal Northern College of Music can at least cling to each other as the night closes in. Interestingly, the opera that came across as the most harmless was the only one that wasn’t created for children.

Ariadne auf Naxos, then. McDonald has updated it to a country house that looks amusingly like Glyndebourne. Neat idea; and so is the notion of transforming the commedia dell’arte troupe into a team of hipster-bearded performance artists. Smartest of all, though, is the decision to make the trouser role of the Composer (Julia Sporsen) a buttoned-up, slightly brittle young woman. At a stroke, McDonald removes one of Strauss’s weaker dramatic contrivances and makes Sporsen’s encounter with Jennifer France’s suspender-clad Zerbinetta into something genuinely transformative. Ariadne as coming-out drama? When the pair suddenly, startlingly locked lips to a cascade of molten harmony (the Scottish Opera orchestra under Brad Cohen sounded like all their Christmases had arrived at once), the audience sighed.

But that’s just the Prologue: and having made all these backstage relationships fizz, it’s hardly the director’s fault that Strauss and Hofmannsthal then ditch the whole set-up in favour of an opera seria, rendered with authentically baroque tedium. Mardi Byers did her best as a dark-toned, eloquent Ariadne, but France’s knockout burlesque routine — imagine Dita Von Teese with a silvery high soprano that can slip like oiled silk over even the most sequin-encrusted coloratura — overpowered any remaining drama. Byers’s climactic love duet with Bacchus (Kor-Jan Dusseljee) had the sexual chemistry of a Scottish widow meeting her mortgage advisor.

Coraline is altogether more serious, as children’s books can be, although nothing in this touching and often magical opera quite matches the ETA Hoffmann-meets-MR James creepiness of Neil Gaiman’s novel. Perhaps that’s just as well; instead, the libretto focuses on Coraline’s courage, as well as the more humorous aspects of the story. The director Aletta Collins makes playful use of the Barbican’s stage, with Giles Cadle’s sets whirling round to represent the sinister parallel world that Coraline discovers in her parents’ new home. The programme lists two separate ‘Magic Consultants’ and the small boy behind me at one point seemed convinced (if impressively unconcerned) that Kitty Whately’s hand had genuinely been chopped off.

Turnage’s chamber-sized score (Sian Edwards conducted the Britten Sinfonia) is unexpectedly subdued, tending towards cor anglais-tinted lyricism over quietly bustling rhythms, with occasional, improbable flashes of colour — an orchestra of mice turned out to be a piccolo-led swing band. But it certainly evoked the story’s overcast atmosphere, and the opera’s final affirmation was skilfully prepared. Whately transformed smartly from the put-upon Mother to the insinuating, increasingly uncanny Other Mother; Alexander Robin Baker’s red-trousered, dad-dancing Father got a lot of laughs, and as Coraline Mary Bevan was a believably bored little girl whose sunny voice and inquisitive nature weren’t remotely cutesy, and who (like the entire cast) made Turnage’s vocal writing sound as fluent as Mozart. Parents, meanwhile, will doubtless mouth a silent ‘thank you’ at the show’s moral that there are worse things in the world than going to school.

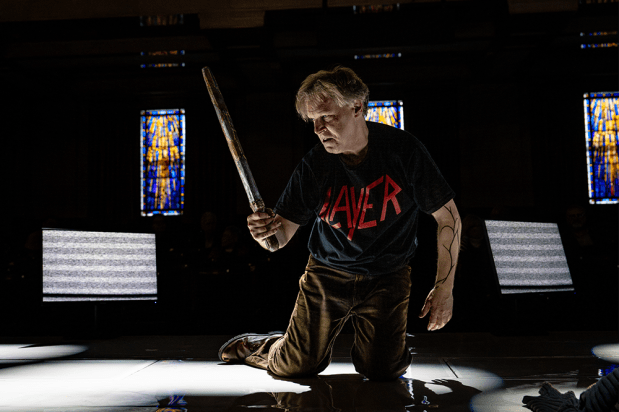

And if you can’t truly believe that things are going to turn out badly for Coraline; well, that’s never stopped Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel from showing a darker side, and in Medcalf’s subtle and inventive new production the supernatural elements are actually the least menacing (Iain Henderson’s brandy-swilling Witch was pure pantomime). We’re in a Victorian industrial city and the children (Daniella Sicari as Gretel, and the lustrous-voiced Charlotte Badham as Hansel) alternate, as pre-teen siblings do, between kicking, pinching, spite and clinging affection. But while Humperdinck’s music gives us the children’s enchanted perspective, Medcalf repeatedly pulls back to reveal some very adult threats. The forest is a maze of street lamps (Yannis Thavoris did the sets), and Hansel and Gretel think that the lamplighters with their glowing wands are angels.

Come dawn, however, when the Dew Fairy (a milkman) gazes down at the filthy urchins huddled on the pavement, we’re a long way from Coraline with her nicely-brushed hair and shiny yellow wellies. Anthony Kraus conducted, the student performances would have graced any professional company, and with luck we’ll see this production (it’s billed as a collaboration with Grange Park Opera) elsewhere, because it’s got ‘classic’ stamped all over it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in