When Winston Churchill was at the nadir of his career, he wrote a biography of his ancestor, the Duke of Marlborough. In his wilderness years he needed to be reminded that even the greatest men of destiny go through periods when it all seems pretty hopeless. ‘Every taunt, however bitter; every tale, however petty; every charge, however shameful, for which the incidents of a long career could afford a pretext, has been levelled against him,’ Churchill wrote. Those Blenheim Palaces and Finest Hours: they don’t just give themselves away, you know.

I wish someone had told me this when I was younger. Unfortunately, like many of us, I suffered the misfortune of having parents who kept telling me how very special I was. This gave me the mistaken impression that life is a piece of piss and that so long as you work hard, do a bit of exercise and are generally nice to people everything will work out fine. Whereas in fact, as most of us have discovered by the time we’ve reached 50, it’s a bit more complicated than that.

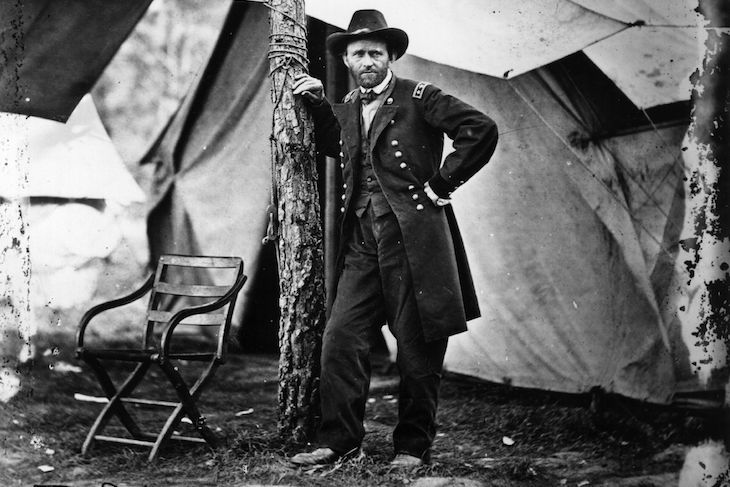

As a corrective to such naivety, I heartily recommend Ron Chernow’s biography of Ulysses S. Grant. It’s a doorstopper of a book (by the author of Hamilton, on which the musical is based): too heavy to take on the train, requiring a cushion to rest on in bed, lest it crush your bollocks. But besides telling you lots of invaluable stuff you probably didn’t know (Mexican-American war 1846-1848, anyone?) it’s a rollercoaster ride. It takes you from lows of the most exquisite schadenfreude to extraordinary highs which make you wonder: ‘Well maybe there is a divine plan for everything, after all.’

On first glance, Grant was one of those great historical figures you wouldn’t have minded being: arguably the greatest American Civil War general, later president of the US, but also a supremely kind and likeable man, loved by his wife Julia and his kids (one of whom, Fred, he took aged 12 to the siege of Vicksburg where a bullet grazed his thigh), and with certain skills akin to superpowers. One of these was brute strength. Even when he was in the White House he was strong enough (or so Julia claimed) to do 25 to 35 pull-ups without breaking a sweat.

But his greatest skill lay as a horseman. At West Point (where most of the future Confederate and Union generals studied together), he memorably closed the graduation ceremony by leaping on his horse over a bar higher than a man’s head. Later, in the Mexican wars, one of his hobbies was breaking in wild horses. And during one characteristically daring escapade, he raced on his trusty steed through the enemy lines under heavy fire and leapt a wall in order to carry through a vital despatch.

You’d think that such qualities would have marked him instantly as a man to watch. But no, he was considered a very average student and wasn’t even admitted to a cavalry regiment. When later the Civil War broke out and the Union was looking for officers with combat experience, it was touch and go as to whether he’d ever be given a command. Indeed, while kicking his heels, Grant reached such a low ebb that he came close to giving up and abandoning his military ambitions altogether.

Grant had at least two major flaws to counteract his superpowers. The first was that he was prone to alcoholism. When bored, away from his wife, or to wind down after a battle, he’d go on massive benders. These were exploited by his enemies and his many envious, less-talented rivals who’d continually gripe that he was unfit for command. This was unfair: he never took alcohol at moments when it mattered. But if it hadn’t been for the support of Lincoln, he might well have been demoted or cashiered.

His other vice was his gentleness and willingness to think well of others. On the plus side, this made him a magnanimous victor: after Vicksburg, he allowed the defeated rebels to return home, with their side arms, under parole, rather than send them north to a PoW camp. The downside was he was useless in business (his genius was as a military tactician and strategist; without the Civil War it’s unlikely he would have amounted to much), far too generous with his limited resources and too trusting of people who turned out to be conmen.

The worst of these was a Bernie Madoff-style character called Ferdinand Ward, who betrayed Grant just when he must have thought all the hard work was over. He’d won the war, he’d been president. Yet suddenly, here he was in his late fifties, utterly destitute and, worse, with fatal mouth cancer.

Was this divine providence at work? The mouth cancer was the product of the 20 or 30 cigars Grant smoked a day. These in turn were a consequence of his military prowess: after his first big victory he became such a celebrity that fans all over the North sent him boxes of cigars. As for the cancerous tumour — of course it was agony and left Grant almost unable to speak. But together with his sudden renewed poverty, it was the impetus for his final great endeavour: the autobiography he’d hitherto resisted writing.

Knowing time was short, holding back on the morphine that might have relieved his pain, Grant hand-wrote up to 15,000 words a day of lucid, brilliant prose. Anyone who has ever struggled with a book should bear this in mind before they next complain about writer’s block. Grant died within days of completing it. The two-volume set saved his widow’s bacon. What a life! What a man! What an example!

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in