Patrick Mason’s new production of Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette reminded me of something, but it took a while to work out what. We saw shiny black walls with chrome Bauhaus details, and a swirl of mist through which beautiful people moved in black formal wear. Then Olena Tokar made her entrance as Juliette, and as she pirouetted about the stage, evening dress sparkling, it clicked. It’s a perfume advert. The artificiality, the chic, the sexy little hint of affluence with top notes of fascism: you half-expected billowing curtains to reveal a giant bottle of Chanel No. 5.

It fitted right in at West Horsley, where the programme book contains adverts for private equity firms and first nights begin with an onstage shout-out to Laurent-Perrier. If it were an hour shorter, Roméo et Juliette might even be the perfect opera for a certain segment of the country-house circuit. Everyone knows the story and while it has its moments the young lovers’ death scene is certainly no ‘Liebestod’. It’s the product of a slightly kinky operatic tradition, rooted in French classicism, that enjoys the sensation of emotions within elegantly proscribed boundaries, and knows that not everything has to be profound.

Gounod delivers transient pleasures in sumptuous profusion: whether the Grande Cuvée sparkle of an anachronistic waltz song, the languishing curves of his melodies or the way he saturates his score with colours that glow from within. And then, gracefully, it slips from the memory. Nothing here to put you off your picnic. Mason and the designer Francis O’Connor handled it with style, though I’m not sure that having the Capulets dressed as Mussolini’s Blackshirts (the setting was a glamourised 1930s Italy) didn’t skew the central conflict too heavily, or that it was wise to have Tybalt’s ghost appear, Banquo-like, at critical moments later in the drama when everything prior to his death had seemed basically naturalistic, in a Baz Luhrmann sort of way.

Still, the company carried the concept, by and large. Mats Almgren as Frère Laurent sang with such enveloping warmth that you completely forgot to question the irresponsibility of his actions. Anthony Flaum, as Tybalt, had a lip-curling swagger that was a nice counterpoint to the elegance of Clive Bayley’s Count Capulet, who carried his melodies with the throwaway charm and tastefully faded tone of Maurice Chevalier until suddenly, startlingly, his face and voice curdled with hatred as he bent over Tybalt’s corpse. Stephen Barlow, conducting the ENO orchestra, is a master-pâtissier in this sort of high-calorie repertoire. He made the score glint, layering divided string passages like a millefeuille, and paced the climaxes nicely, while letting the love scenes breathe and expand.

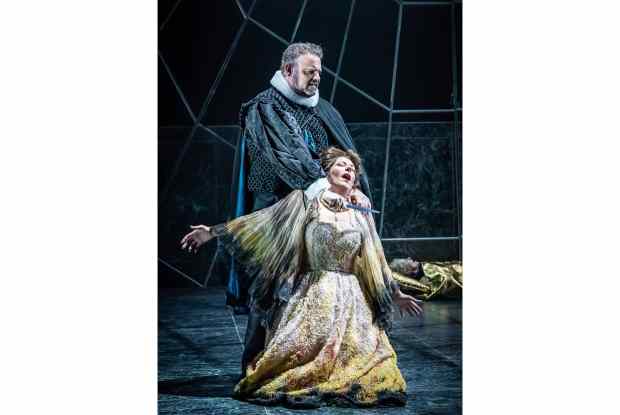

But it takes two to make a love scene, and the kindest thing to say about David Junghoon Kim’s Roméo is that vocally he’s a fighter, not a lover: more convincing when powering over an action scene than in his shared moments with Juliette, though Mason must take some responsibility for the unenthusiastic way Kim shambled about in his shirtsleeves. Yet as Juliette, Tokar was a knockout: throwing out jets of coloratura, singing her love music with sensuous, translucent fragility and acting with a sort of super-stylised self-consciousness. She struck classical poses, opened eyes and mouth wide in rapture, and darted balletically about the stage. Nothing she did looked natural, but everything was magnetic — as if character and performer alike were equally aware that they were simply part of some fabulous luxury product. In this context it was spot-on, and on the strength of this performance I’d hear her in anything.

That doesn’t leave much room for John Copley’s new staging of The Abduction from the Seraglio, which is merciful because colleagues tell me he’s a national treasure, and no one wants to blame a national treasure for wobbly sets, drab lighting and a representation of Islamic culture that, with its funny hats, pointy slippers and perma-smiling harem girls, had all the sensitivity of an ITV production of Ali Baba, circa 1978. The cast seemed uncomfortable with the spoken dialogue (the English translation was embarrassingly dated). Only Jonathan Lemalu — playing Osmin as a teddy bear, but singing nobly — and the comic couple of Pedrillo (Paul Curievici) and Blonde (Daisy Brown) really seemed to be enjoying themselves, though Kiandra Howarth, as Konstanze, won cheers for ‘Martern aller Arten’.

The Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra was in the pit, and with Jean-Luc Tingaud drawing sparky sounds from the percussion section there was the consolation that the enterprise was at least redistributing some wealth in the direction of an undervalued regional orchestra. Meanwhile, I’m not saying that this opera has to be set in Fallujah but there are ways of exploring its central tensions that make it considerably more than just a silly posh panto. Assuming that’s what the Grange Festival actually wants.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in