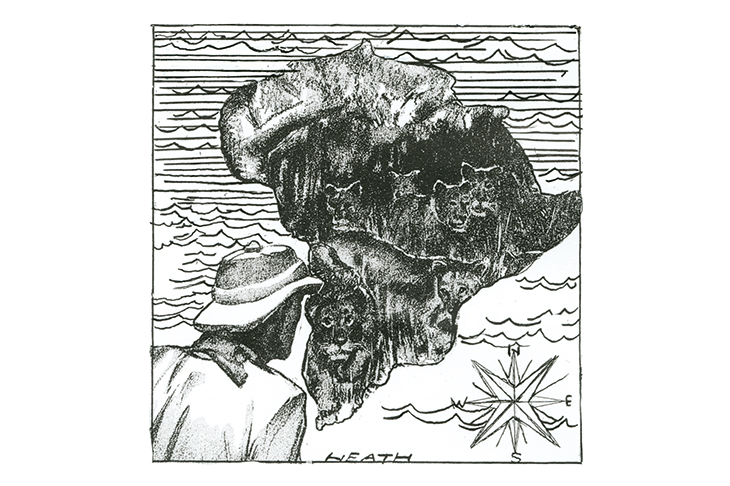

No one likes uncertainty and in Britain we’ve got more than our fair share. But spare a thought for South Africa, where the uncertainty is in danger of morphing into national paralysis. ‘What are your plans for the future?’ I ask a friend who lives near Durban. ‘We have no plans. We might be packing up next year and heading out.’ A lot rests on next year. The general election appears to be set for May and with every day the pressure on President Cyril Ramaphosa increases. The 65-year-old millionaire is stuck between the rock of his more militant ANC supporters and the hard place of those impatient for root-and-branch change. Which means stamping out corruption, tackling unemployment (some commentators put it at 40 per cent), dealing with violent crime, resolving the redistribution of land issue and rehabilitating, variously, the tax collection agencies, police investigation teams, security firms and the prosecution service. That’s for starters. No wonder Ramaphosa is lying low. ‘I am going to vote for the ANC for the first time in my life and just hope Ramaphosa wins a thumping majority and then sets about rebuilding this country,’ says my friend’s husband. ‘Right now it could go either way.’

The lying-low policy is not proving easy. I awake to headlines about how the president’s finance minister, Nhlanhla Nene, has resigned over links to the notorious Gupta family, who allegedly controlled cabinet appointments and state contracts during Jacob Zuma’s disastrous nine-year presidency. Within hours, the rand falls and the prospects of the appalling Julius Malema, leader of the far-left Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), seem brighter. Then comes news that the Zulu king, Goodwill Zwelithini, is forming an alliance with a hard-line Afrikaner group to protect tribal territory and that ‘anyone who wants to be elected by us must come and kneel here and commit that [he] will never touch our land’. Never mind that former interim president Kgalema Motlanthe has described leaders such as King Goodwill as ‘tinpot dictators’.

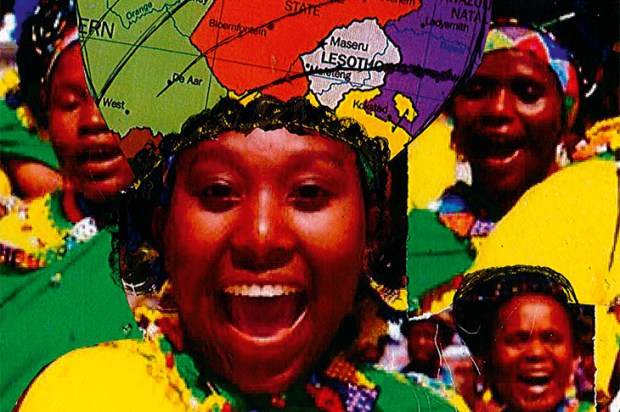

And yet South Africa is also joyful. We stop for petrol at a service station near Melmoth deep into KwaZulu-Natal. A smiling young man offers to clean our windscreen for ten pence, and a ‘hot hero’ sandwich costs 90 pence. An elderly, aristocratic white woman is speaking fluent Zulu to a woman behind the counter and soon every member of staff is listening intently before bending double in laughter. Apparently she’s telling them she’s had a furious row with her farmer husband and is looking for a ‘hot hero’ to cheer her up. The banter continues back and forth. No one gets served for the next five minutes, but customers leave with clean windscreens and happy hearts. Things are a little different at the Welcome Break service station on the M4 near Junction 15.

Roelof ‘Pik’ Botha, who died last week, was a government minister who served in both the white National Party and Nelson Mandela’s ANC government. He said South Africa was like a zebra: ‘If you put a bullet into the black stripe or the white stripe, the animal will die.’

There are hitch-hikers in this province. They tell you where they are going via sign language. An up and down motion of the hand means they are heading for the coast; palm facing down means they just want to get to the next village; and a raised palm means they are happy to give a few rand in exchange for a lift.

For all the chaos, British Airways is about to start direct flights from London to Durban. Smart move. Safaris here tend to be cheaper than in hot spots closer to Johannesburg, and the Indian Ocean is gloriously warm, with designated swimming areas protected from the killer sharks. If you’re partial to a curry, you’ll like Durban, which has the highest concentration of Indians anywhere in the country. Direct flights also make it easy to stay at the iconic Oyster Box about 20 minutes up the coast in Umhlanga. Owned by the indefatigable Stanley and Bea Tollman (both well into their eighties) and part of the Red Carnation group, it was rebuilt in 2007 at a cost of more than £30 million but remains loyal to its colonial past. The Palm Court, where high tea is served, has chandeliers bought at auction from the Savoy Hotel in London.

My father-in-law was a district commissioner in Malawi leading up to when the country gained its independence in 1964. On official duties he sported a crisp white suit and pith helmet. I am forever under instructions from my wife to bring home a helmet similar to the one her father wore. It’s never happened. But when I arrive at the Oyster Box, the doorman is wearing just the job. I ask him if he knows where I might find one. ‘Talk to Mr Wayne,’ he says. Wayne Coetzer is the genial general manager. I track him down and pop the question. ‘I have a spare one in my office and it’s all yours,’ he says, adding that his mainly black staff love wearing their pith helmets and even chose to do so recently when asked to vote on the matter. Elections in South Africa can throw up surprising results.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in